Randi Wenzel says even basic operation of a drone over annual crops and pastures on their south-central Saskatchewan mixed farm provides some very useful management information, along with some peace of mind.

Wenzel, who farms with family members south of Central Butte, has been flying a drone during the cropping and grazing seasons for the past three to four years. She says it doesn’t eliminate the need to be out in the field, but photo images collected by a drone can give her a much better view of what’s happening over an entire crop.

Read Also

Bourgault rolls out new drill, opener and upgrades to BiC system

Bourgault in mid-January announced the release of three new products for its 2027 model year lineup: a new 50-foot drill, a new twin-shank opener and an upgraded BiC system.

“I still have to be out there checking crops,” says Wenzel, a professional agronomist. “But I can go to one location, for example, get a sense of how the crop is doing, then send the drone up for a look at a much larger area. With the drone I can identify a thin area of the crop, or get a better sense if there has been some cutworm damage. The images also give me a better sense of pre-harvest staging. It can alert me to areas of perhaps higher concern, which I might have otherwise missed. It gives you that bird’s-eye view of the field and it really does change your perspective.”

On the livestock side, the drone provides that bird’s-eye sweep of pastures to help locate cattle. Wenzel says the drone has been useful, for example, in helping to track down a missing bull on pasture, and also has been used to make a final pass over some bushy pasture to make sure all cattle have been collected during the fall roundup.

“When we’re at the corral with trucks waiting, once everything has been gathered, I can send the drone out for a final look into the farthest corners of the pasture, just to make sure nothing was missed,” she says. “So in that respect it provides peace of mind.”

Wenzel has found cattle do need to adjust to the technology. “I have to be a bit careful so as not to spook the cattle,” she says. “The cows need to get used to it. It’s not so much the visual aspect but the drone does make some noise. I don’t use it much in winter because I don’t want to get pregnant cows startled if the ground is icy.”

Wenzel uses the drone to check crops and cattle on the family farm, and also for checking the crops of clients in her role as an agronomist for Rack Petroleum. “I think initially I thought it would just be handy for taking fancy videos around the farm,” she says. “But the more I investigated and heard from others on social media, I soon came to realize it could do much more.”

Drone school graduate

She initially “played around” with drones on her own and eventually attended a two-day Ag Drone School offered by LandView.com of Edmonton, Alta. The company, launched five years ago by Markus Weber, offers the only drone certification school in Canada specific to agriculture.

“We started with 25 farmers in the first classes four years ago and last year more than 250 farmers across Western Canada attended the schools,” says Weber. “People can go online to apply for registration as operator of a Remotely Piloted Aircraft, but we’re seeing people appreciate the classroom experience. They get to see and work with different models of drones, get some experience with flying drones and also get some understanding of the broader application of drones in crop and livestock production.” On the second day of the school, students can complete their drone operator’s certificate.

Weber says there is a wide range of prices and drone models. He recommends farmers get a very useful, good-quality drone, outfitted with a quality-camera for between $2,500 and $3,000. “Those entry-level units can provide a lot of basic information to producers,” he says. “And then as they go along and are interested in more functions, the hardware is still useful, it is a matter of adding more apps.” On the top end of the scale, he says, the real serious drone operator can spend $25,000 to $30,000 or more.

Wenzel says the Landview drone school was a good starting point. “So far I’m sticking with some of the basic operations of a drone, although I know from a crop and livestock management point of view the drone can have broader use down the road,” she says.

One of the requirements for drones used by agricultural operators is that the operators must always maintain line of sight with the machine. Wenzel says it is usually not a problem on a quarter or half section of land to find a vantage point where she can maintain visual contact with the drone even at the farthest points.

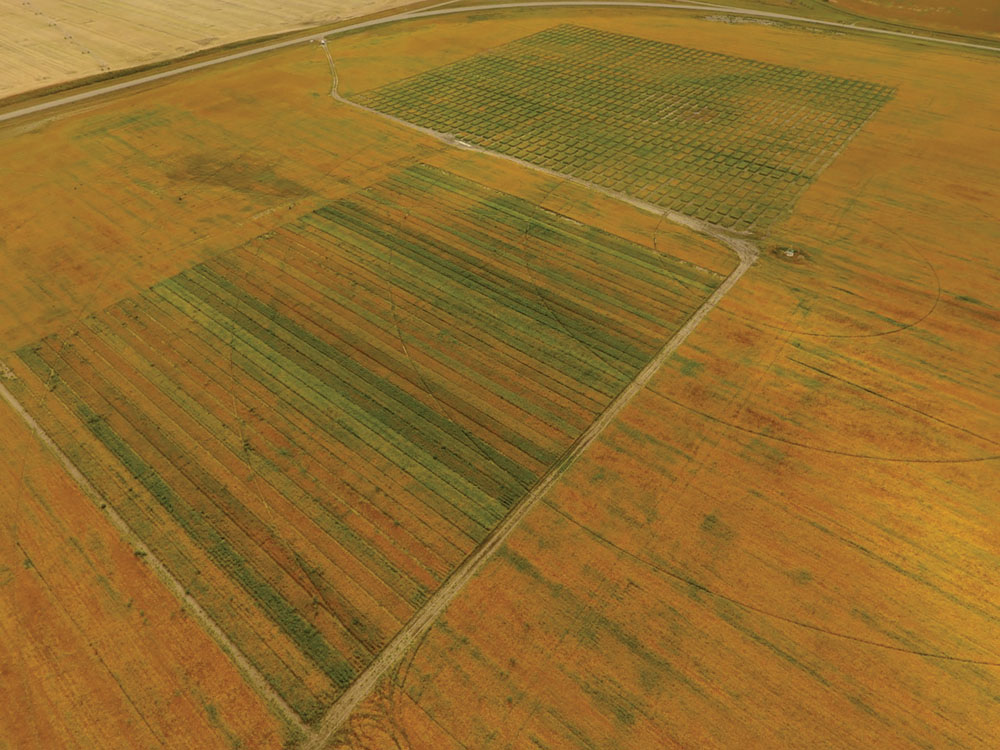

For quick spot checks, Wenzel can fly the drone herself, however, if she’s interested in a more detailed look at a field of canola or peas for example, she can program the drone to fly and photograph a grid of the field, taking photos every three seconds. “With the grid the drone covers the field on autopilot,” she says.

With basic operation, the drone will produce quality colour photo images over the field grid. “And the option is there, if I wanted to make a further assessment of crop health, for example, I would need to buy more software,” says Wenzel. Downloading an app that would convert photos to NDVI imaging (normalized difference vegetation index) would cost about $1,200. “It might be something to add down the road, but it’s a cost I really can’t justify right now,” she says.

A view of the whole crop

Central Alberta farmer David Carlson says basic drone imaging gives him a much better sense of how the whole crop is looking.

Stopping in a couple of different locations in a canola field, for example, on his farm near Gwynne, east of Westaskiwin, Carlson says he can launch the drone to “zip across a quarter section in a matter of minutes.”

As the drone camera transmits images back to an app on his smartphone, he can see real-time images of crop over the rest of the field. He can look for insect damage, weed patches, areas of poor-performing crop, look at overall crop colour and get a sense of crop maturity.

“The value for us so far is more about field-specific verification,” says Carlson who farms with family members including his son Brendon. They began using the drone in the summer of 2019. “We know how the crop looks in the immediate area where we are standing, but how does it look over the rest of the field?”

Carlson, who crops wheat, malt barley, canola, peas, fababeans and sometimes quinoa, figures the drone is complementary to services provided by the farm’s crop consultants, Farmers Edge. As part of its agronomic services, Farmers Edge works with satellite imagery for the Carlson farm.

While the satellite imagery is useful, the drone camera allows them to have a look at the whole field, as well as focus on specific spots. “We assume the crop is looking a particular way, but with the drone images we can get verification about how the rest of the field is doing,” says Carlson. “Those images might alert us to walk into certain areas for a better look.”