I will dedicate this piece to the memory of Bill Meneley (1933-2000), a hydrogeologist of much renown and our special consultant for the soil salinity work of the 1980s and ’90s.

Those of you long enough in the tooth might remember the famous Red Adair, who was called in whenever a problem oil gusher was encountered. Bill Meneley was the Red Adair of the water well industry. In later years, we worked together as consultants on irrigation projects.

We were drilling for soil salinity work at Beechy and encountered an aquifer with great pressure. It took us three tries to plug it. It was not a good sand aquifer, so we did not lay much water on the ground.

Read Also

Southern Alberta farms explore ultra-early seeding

Southern Alberta farmers putting research into practice, pushing ahead traditional seeding times by months for spring wheat and durum

We released the driller to the farm of Gerry Weins, to drill a well near his new home. We recommended he drill away from the house in an area that had good drainage.

If he hit the aquifer we encountered, and if it had the sand and gravel of the Beechy town well in the same aquifer, it could get ugly. And it did. A little over 100 feet all hell broke loose.

Because there was drainage, they were able to complete a well that had three, two-inch gate valves, and all three were left open. As the cement dried, the taps were closed one at a time. The head was estimated to be 52 feet above soil surface. That equates to a pressure of 65 psi in the aquifer. Weins had running water in the second story of his house!

Flowing wells, a classic explanation

The illustration below shows the aquifer cropping out at the soil surface to receive the rainwater and pressuring up to create artesian conditions. I know of a few situations like that on the Prairies but that is not how most of our flowing wells are plumbed.

Artesian and flowing artesian?

Artesian means the water rises above the level of the aquifer. Flowing artesian occurs when the pressure is enough to lift water above the soil surface so it flows.

Geology of flowing wells in Saskatchewan

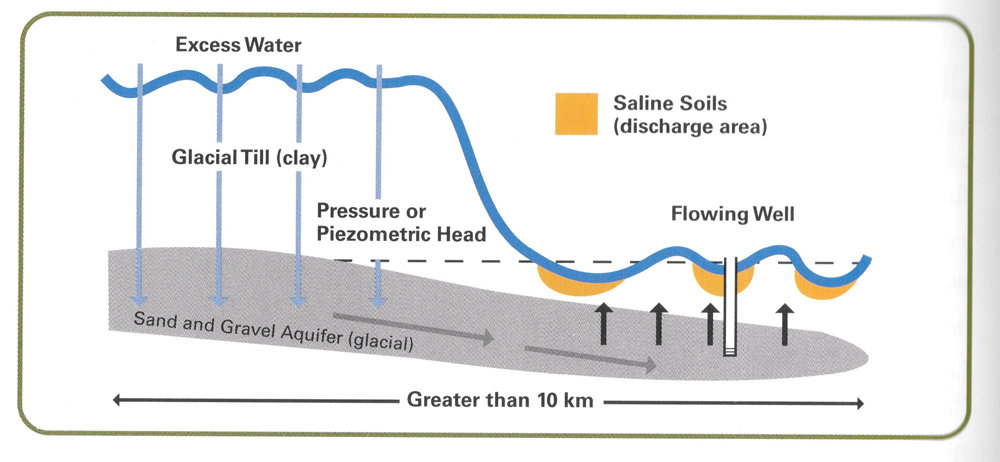

The illustration below shows the geologic setting for most flowing wells in Saskatchewan and areas of Alberta and Manitoba with thick glacial deposits. The sloughs in the upland catch the water that drains slowly through the glacial till and feeds the aquifer.

Where the aquifer pinches out on the Plains, it pressures up creating flowing conditions. The pressure keeps the water table high even in dry spells and soil salinity is the result. This was figured out by Peter Meyboom and others in the 1960s and was referred to as “the Prairie profile.”

It does not need to be very hilly land to set up the condition of pressure that can result in a flowing hole.

The Halloween caper, 1986 near Zelma

Oct. 31, 1986, which was a Friday, provided us with some excitement.

In our soil salinity work, we encountered many flowing test holes within the depth we could reach with an auger (73 feet). By 1986, we thought we knew what we were doing. We went to investigate a saline area in a low area of a field near Zelma, Sask.

We spent the day completing a nest of piezometers at a comfortable elevation above the problem. A nest measures the pressure at various depths, so we would know the direction of groundwater flow: up or down and how much gradient there was. As it turned out, the aquifer causing the soil salinity was not even present where we located the nest of piezometers, so it was a waste of time. The culprit aquifer was a “finger” aquifer not a “sheet” aquifer.

While the boys were installing the nest of piezometers, I was using the EM38 to scout out how big the saline area was and how salty. About 3 p.m., I found an area with an unusual EM38 reading. I said we would drill there to 30 feet, and if we found nothing, we would call it a day.

At about 20 feet, we struck an aquifer that came at us like a gusher. We put a screen on a two-inch PVC pipe, which we were using to plug the hole. It was not working. I knew Meneley was away, so I phoned John Soloninko from Elk Point Drilling at North Battleford, Sask., who had much experience with flowing wells.

He said we were doing it all wrong and should get rid of the screen and do it open hole. He suggested we wrap a two-inch PVC pipe with gunny sacks and push that down the hole and to use barite (barium sulphate density 4.0) to plug the hole so water would be coming out of the pipe, preventing a crater. We had used up most of our barite doing it wrong, so Soloninko said use sand for weight on top of the barite.

I stood over the hole holding the pipe against the pressure while the boys poured the barite and sand on top of the bottom plug of bags. It was all I could do to hold it in place — but it worked. We then put a 90-degree pipe on top to shoot the water sideways, and it was safe to let it flow.

How not to plug a flowing hole

Earl Christiansen, who was with the Saskatchewan Research Council, drilled a test hole near near Whitkow, Sask. Christiansen and the driller tried to plug it by pushing a large pole down the hole. The photo below shows the pole being pushed into the hole.

That did the trick but shortly after water was spurting out in the adjacent farm’s field. Meneley was consulted and he said, “You must drill out that pole and then plug the hole from the bottom with mud heavy enough to contain the pressure.”

Barite is used to make the cement mixture heavy enough to contain the pressure. Drillers have a special mud balance to easily check the density of the drilling fluid. But how does one know what density is required? If you get it too heavy, the mud will go out into the aquifer. If the density is too light, the hole will continue to flow.

The answer to follow!

Meneley’s digram

Readers with Henry’s Handbook of Soil and Water can check out page 187 to find Meneley’s diagram. The diagram he prepared combined the depth of the hole, the estimated height above the ground water would flow and then the estimated mud density required.

In the later years of our soil salinity program, we never went anywhere without Meneley’s diagram.

The Brightwater Marsh caper, 1976

There was one test hole even Meneley could not plug.

In 1976, he investigated a site just south of Dundurn, Sask., where a previous drilling program found a very high head aquifer and he had to bring in big Alberta equipment to plug it. A crater from the previous gusher was still in place but there was little information on the geology of the situation.

By that time, Meneley had much experience in controlling flowing conditions, so he drilled again but with many precautions. He first drilled to 80 feet and cemented in a casing to prevent cratering when flow was encountered. The top 30 feet was sand, so that meant a serious flow would quickly crater with danger to equipment and men.

At 180 feet, the hole started a serious flow with large volumes and high head. After a long struggle, it was obvious they were going to lose. Meneley’s notes said, “09:50. 10/3/76. Moved rig off hole. 09:52. Hole cratered 30 feet in diameter.”

It came down to a matter of minutes and judgment to know when to give in. Two minutes later equipment and men could have been lost.

The hole was then allowed to flow until Halliburton Equipment was hired from Alberta, with huge pumps and fast-drying cement, and the hole was plugged.

Meneley showed me the site in the 1980s and all was quiet. The thing that struck me was there was no salinity. The reason was the glacial till on top of the aquifer was so tight that upward movement was prevented. Where salinity is present, the aquifer is venting its fury in delivering the water that causes the soil salinity as evaporation carries away the water.

The complete report of the Brightwater caper was published as “Control of SRC (Saskatchewan Research Council) Brightwater Marsh Flowing Test Hole. Miscellaneous Report No. 0129.”

A copy of that report is available at the Wilson Museum in Dundurn, and I have a personal copy at my home office.

The observation well network

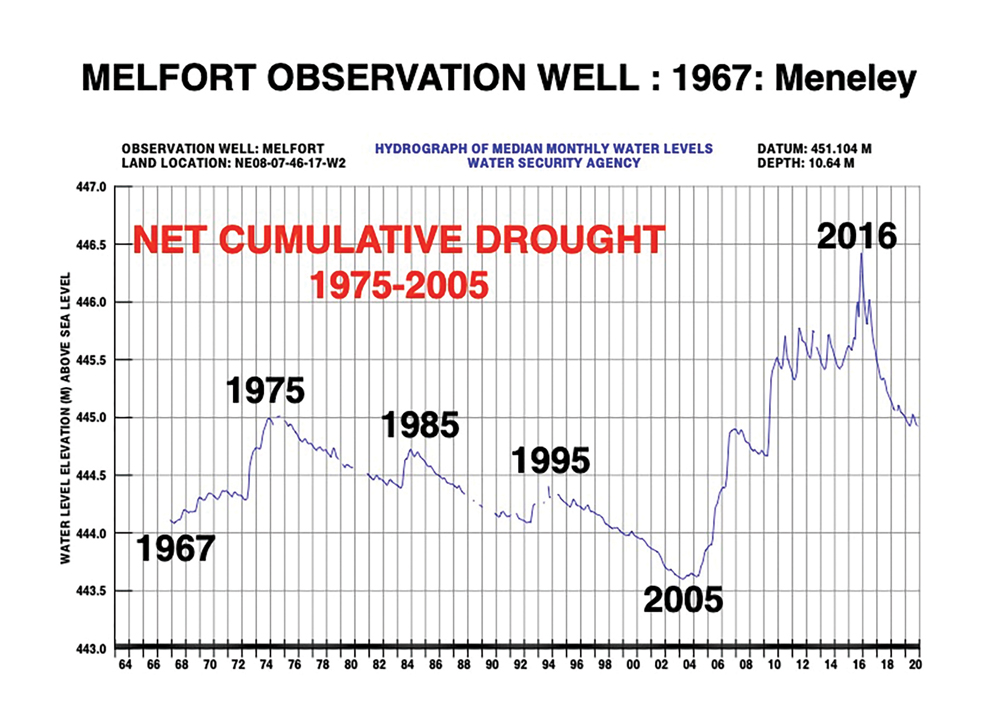

While working at the Saskatchewan Research Council, Meneley installed a large series of observation wells in areas not affected by pumping to monitor natural changes in water levels. Those wells are now in the care of the Water Security Agency in Moose Jaw, Sask., and hydrographs and other details are available at https://www.wsask.ca/water-info/ground-water/observation-well-network/.

This Melfort observation well hydrograph is one we have used to document a net cumulative drought from 1975 to 2005. The Goodale Farm observation well near Saskatoon is also in an unconfined, surface aquifer and shows the same trend, as does Atton’s Lake (west of North Battleford).

In closing, Meneley has left a legacy that will be with us for a long time. Thanks, Bill!