During the first couple weeks of January, auction markets in Western Canada experienced a surge in sales as cow-calf producers increased selling prior to the Trump inauguration.

Feeder cattle markets have been trading at record highs, which may have contributed to the feeder cattle liquidation; however, most cattle producers were selling in anticipation of U.S. tariffs on cattle and beef.

Since President Trump won the U.S. election, I’ve been overwhelmed with calls from cattle producers asking how tariffs will influence the price of cattle in Western Canada. In this issue, I’ll discuss the expected implications on the cattle and beef markets. Cattle and beef are unique commodities compared to wheat or even steel. This is because the demand curve is rather steep. The influence of a tariff on beef or cattle is totally different than a tariff on other commodities. I’ll specifically discuss the fed cattle situation because Canada has become a net importer of feeder cattle.

Read Also

Cereal lodging isn’t just a nitrogen problem

Lack of copper in the soil can also lead wheat and other cereal crops to lodge during wet seasons on the Canadian Prairies.

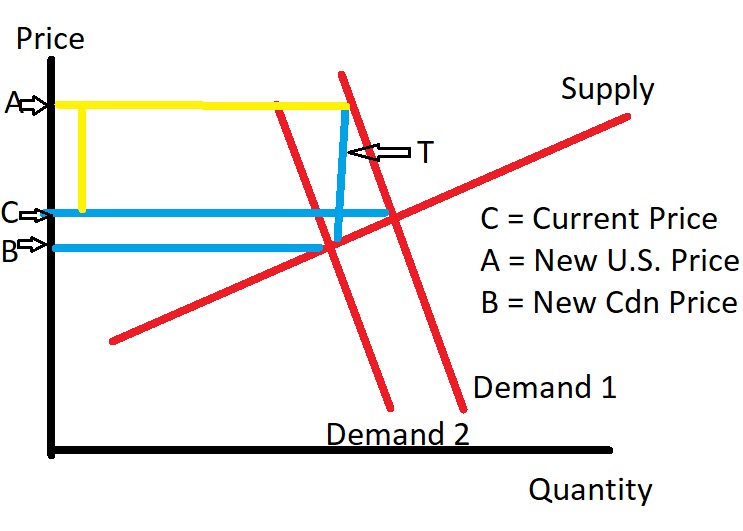

First, the demand curve for cattle and beef is inelastic. A small change in quantity has a large influence on price. The beef demand curve is more vertical than horizontal. This compares to the demand curve for wheat, for example, which is rather flat or more horizontal. Consider the diagram shown here.

We can say that Demand Curve 1 is the Canadian/U.S. demand curve in the current environment, where fed or finished cattle move across the border with no tariffs. The Supply Curve represents the total supply of North American fed cattle. We can say that C is the current price of fed cattle, where Demand 1 intersects with the Supply Curve.

A tariff of 10 per cent would cause the North American demand for fed cattle to fall to Demand 2. This is the new demand curve faced by the Canadian feedlot operator. The new price for the Canadian producer would be B,2q where the Demand 2 intersects with the Supply curve. The price faced by the Canadian producer would be lower as the demand curve shifts left.

The opposite is true for the U.S. company buying Canadian fed cattle or beef. The importing company continues to face Demand Curve 1 but there are fewer finished cattle coming into the U.S. This causes the price to increase to A. Notice the price increase in the U.S. is larger than the price decrease in Canada. A 10 per cent tariff on Canadian fed cattle or beef would eventually be absorbed by the U.S. consumer which would pay higher prices.

U.S. wholesale beef prices usually make seasonal lows in January and February. At the time of writing this article, wholesale choice beef was trading at US$333/cwt, which was a fresh 52-week high — and higher than the monthly average COVID high during May 2020. The wholesale beef market is incorporating a risk premium due to the uncertainty in the tariffs. Beef is typically sold on longer-term contracts to companies like McDonald’s and packers are anticipating higher prices for fed cattle.

The influence of the tariff on feeder cattle may be neutral as U.S. producers will have higher price for fed cattle and wholesale beef which may offset a tariff on Canadian feeder cattle. If the slope of the demand curve is equal to the slope of the supply curve, the tariff punishment is split equally by the exporter and importing consumer. This somewhat represents the environment for steel.

If the demand curve is flat, the exporting producer bears the full punishment for the tariff and this would be similar to wheat. The U.S. consumer won’t notice a difference on their domestic bread price and the Canadian wheat price would be lower.

President Trump ran a campaign on lowering food prices but if he tariffs beef and fed cattle, he’ll be paying more for his Big Macs.