It’s likely safe to say not many people farming today have heard of a Roto Thresh combine. That isn’t surprising. Only 50 were ever built by the small company that existed for just a few short years more than four decades ago.

According to the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, “The Roto Thresh combine was developed, designed, tested, manufactured, and used in Canada. Manitoba farmers Bill and Fred Streich, with the help of Frank McBain and Barney Habicht, developed and produced the first prototype in 1951. They went on to form the Western Roto Thresh Manufacturing Company in 1968 and produced a more advanced prototype in collaboration with the University of Saskatchewan. Roto Thresh began production in 1974, but only 50 machines were manufactured before the company closed in 1978.”

Unique design

Read Also

Farm equipment market unlikely to pick up

North America’s farm machinery sales have been slow and uncertain thanks to tariffs and trade disruption. There’s not a lot of hope for change in 2026.

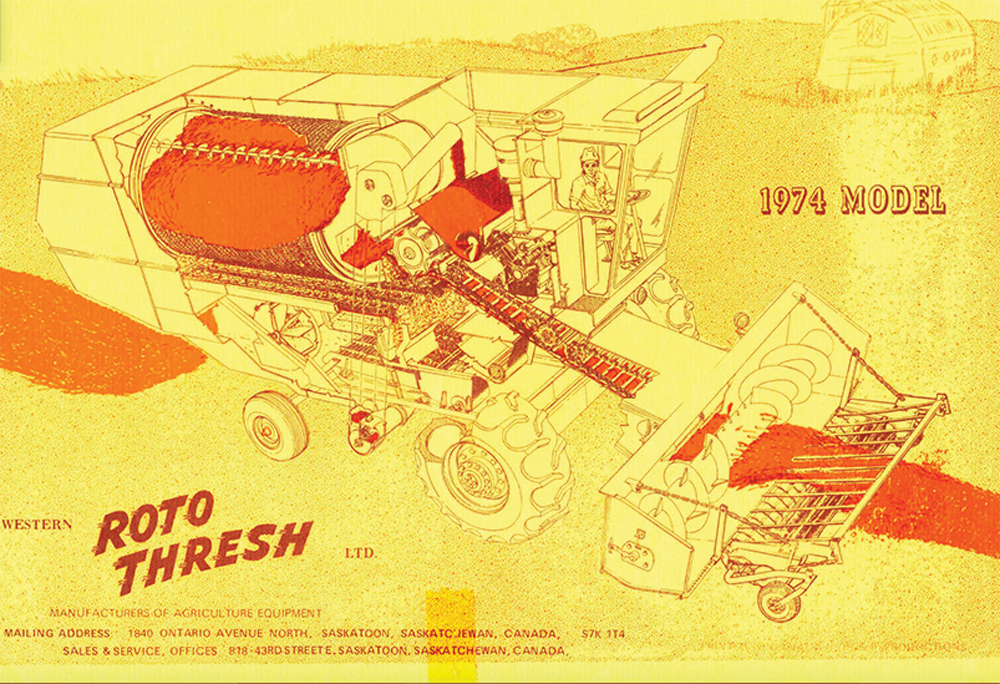

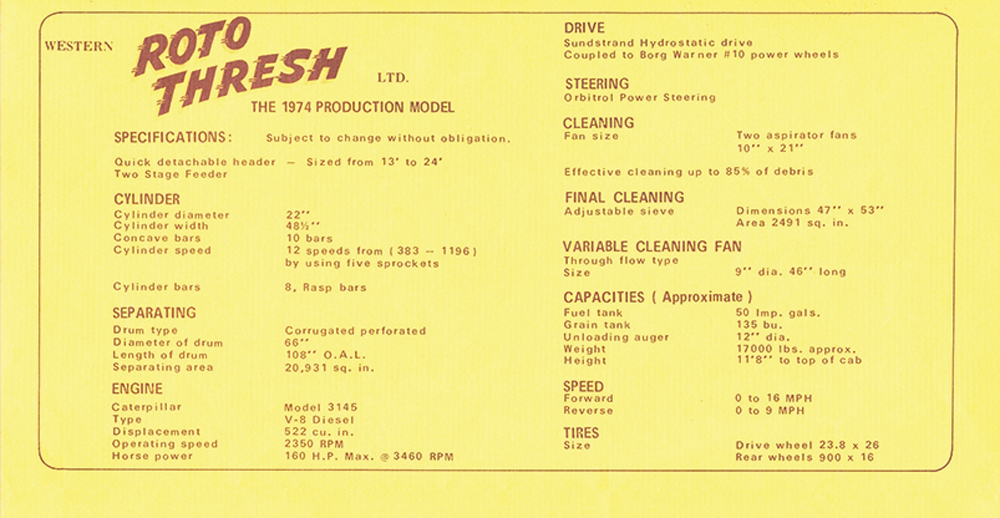

Up front, the Roto Thresh combines begin threshing like a standard conventional combine, with the crop mat flowing through a 48 1/2-inch cylinder. But rather than straw walkers, material moved from the cylinder into a 108-inch-long, 66-inch-diameter, corrugated rotating drum that gave the combine an impressive 20,931 square inches of separating area. Sieve area was 2,491 square inches.

NEW VIDEO: Vintage Roto Thresh combine hits the field to harvest wheat

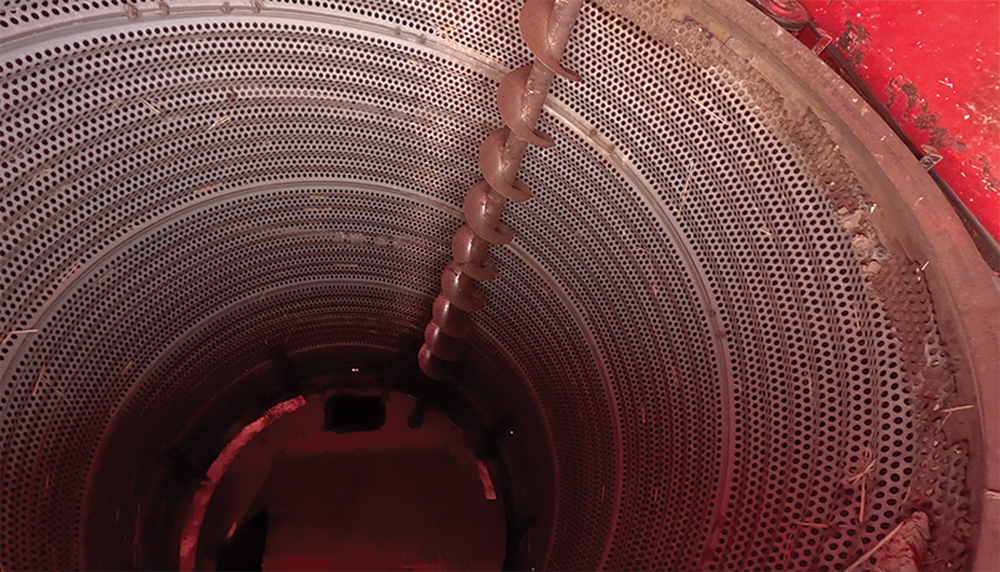

As material passed through the drum, centrifugal force helped in the separating process. The drum was aided by a stripper auger mounted inside to add to the separating efficiency, creating a kind of pulsing action. Company information claimed this gave the Roto Thresh three times the typical separating area of any other conventional combine on the market at the time.

That large drum was the reason for the Roto Thresh body’s boxy shape, much different than a typical conventional combine of the day.

But they also had another unique feature that added to the combine’s ability to produce a very clean grain sample: dual aspirating fans, mounted at the rear, in addition to the typical cleaning fan they and other conventional combines used.

“They suck chaff off the sieves with the aspirator fans at the back,” Milden, Sask. farmer Arnold Somerville says.

“What it produced was an exceptionally clean sample and very efficient sieve for the time period,” adds John Lloyd, son of Mervin Lloyd, the original owner of one of the Roto Thresh combines.

“As the grain fell through the concave onto the sieve, there was what they called an aspirator throat there. At the back, two big aspirator fans sucked air across the top of the sieve. What it did was cleaned a lot of the light chaff, which never actually made it down to the sieve.”

Power came from a 3145 Cat diesel engine mated to a hydrostatic transmission. The engine has an unusual drive attachment design, with the threshing mechanism drive running off the front of the crankshaft and the hydrostatic pump mounted to the rear of the engine. That required the cooling fan and radiator to be offset to the side.

“Their hydrostatic drive system was light years ahead of anything else,” says John, who spent many days as a teenager running the combines for his father. He adds with a chuckle, “Their air conditioning was light years behind everybody else.”

Instead of an HVAC system, the combine cab used an old-fashioned, ice-water cab cooler system. Anyone who’s used one knows their effectiveness was marginal.

John adds that the 160 horsepower 3145 Cat engine had ample power to run the combine.

“It definitely had enough power. Once in a while my dad would shock people who came to see them and run them at double speed. He would push it right up to about six miles per hour. They would handle it, power-wise; it’s just that you would start to throw (grain) over the back.”

As for maintenance and durability, John thinks his dad would have probably said they were quite a reliable machine, though he remembers a lot of the repair work that did have to be performed centred around the large drum.

“The drum basically tumbled the straw and wheat like a clothes dryer. The problem was the drum was driven by a big, long chain, and it had teeth around the drum. Every once and a while you’d get wiry straw in there and flip that chain off, and the straw would back up.

“The drum would be right full of straw. It was easy to get the chain back onto the drum, usually. But it involved someone who was under 16 years old climbing in the back and digging all the straw out. That’s why it wasn’t one of my favourite things.

“The other problem was the drum ran on four large rollers, eventually they would cause problems. Most of the maintenance problems I remember were around that drum.”

The Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute tested the Roto Thresh combine in 1977, and it managed to harvest 11.1 tonnes per hour at a ground speed of 5.8 km/h in a crop of Neepawa wheat. PAMI conducted tests on the Roto Thresh design over two seasons, 1976 and 1977.

The list price for a new Roto Thresh combine in 1977 was $51,900, according to the PAMI report, or about $250,000 in 2024 dollars. That included a 10.5-foot Melroe pickup, straw chopper and spare parts kit.