In 1969 Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the moon. After that, despite being notoriously private and shying away from publicity, he did take on the role of spokesperson for some products, including White Farm Equipment’s newest rotary combine. He appeared at a dealer meeting in Arizona in 1985 to promote the launch of the 9320.

But Armstrong’s efforts in Arizona on behalf of the 9320 would be wasted. As the very first 9320s started down the assembly line, combine production at White ground to a halt. The company declared bankruptcy. But it still had a very desirable asset: a marketable rotary combine.

How did that combine come to be — and what happened to it?

Read Also

TIM system offers improved performance for Hesston balers

TIM, short for Tractor and Implement Management, allows a Hesston large square baler to control the speed of a Massey Ferguson 8S or 9S tractor for better baler output and bale quality.

WHY IT MATTERS: In this article, Scott tells a fascinating story of harvester research and development, much of which took place in secret up here in Canada, showing how even the best ideas could fall victim to quirks of timing and circumstance.

New Holland would be the first to market a rotary combine, the TR70, in 1975 — but all farm machinery brands were working on and/or trying to develop the concept.

After the TR70 debuted, no longer was trying to create a rotary combine just an interesting R&D project for other brands. It became an urgent objective if they were to stay competitive in the harvester marketplace — and the clock was now ticking.

“The whole combine industry changed,” says Doug Voss, a former engineer with White, who worked through that period.

Engineers there had started White’s rotary development project back when the company was known as Cockshutt, long before that brand merged with U.S.-based Oliver and Minneapolis-Moline to form White Farm Equipment in the early 1960s.

“The rotary concept was the brainwave of Don McNeil, who was our chief engineer,” says Herb Hagglund, a former field engineer at White’s Cockshutt facility at Brantford, Ont. “He came from Massey. He and another fellow at Massey — who ended up at International — had tossed the idea around before he came to us at Cockshutt in 1953 or ’54. We started this thing (the rotary development project) in September of 1966.”

Given that IH started a rotary project about the same time, it’s interesting to speculate whether the other engineer from Massey-Harris-Ferguson who went to IH had a hand in that.

The garage band

Once White’s rotary development project was approved, all work on it became top secret — so secret, in fact, the small staff assigned to work on it was moved out of the company’s main engineering facility to a rented workshop. That kept the project as invisible as possible.

“They rented what was originally an Esso service station,” remembers Hagglund. “It had two bays and a bit of an office. We just had the barest of essentials as far as fabrication is concerned. I was in charge of the overall project at that time.”

To help Hagglund, two fabricators and a draftsman were pulled from the main engineering section to make up the team working out of the old service station. A service trailer loaded with tools, used by engineers for field repairs, was hauled up to the garage to give the small crew access to welders and a variety of other essentials.

Although they were essentially working on their own, the team was also getting some R&D support from the Ontario Research Foundation (ORF), which was funded jointly by an industry association and government grants. It helped the small, garage-based research team by doing some testing and development in its lab.

Roy Gullickson, a combine engineer, was recruited away from Massey Ferguson by the ORF to bring expertise in harvester design to its staff. And he was given the job of heading ORF’s efforts on the rotary development project.

“The ORF was involved in a contract with Cockshutt (White) Farm Equipment to take a look the possibilities of having a combine harvester more suited to corn and soybeans, but also suited to cereal grains and oilseeds,” he explains. “That sounded interesting to me.”

To begin evaluating potential rotor designs, long before NH introduced the TR70, Gullickson took a look at the only existing rotary technology on the market at that time, used in stationary corn shellers.

“We bought a small, stationary corn thresher you could drive with the belt pulley of a tractor and you could shovel corn ears into it,” he continues. “The rotor itself was only about six or eight inches in diameter. We did quite a bit of testing on kernel damage and threshing efficiency in a lab that was set up for that purpose in the ORF building.”

Playing by ear

To have corn on hand for testing year-round meant the team members had to leave their workshops, go out into cornfields and hand-pick ears for their stockpile.

“We gathered corn ears in the field,” Gullickson says. “The guys from Cockshutt helped with that and we put the ears into cold storage until we were ready to use them.”

Because he’d contributed so much to the overall project, management at White decided to bring Gullickson into its own fold. He was hired away from the ORF to be a full-time member of the rotary development team.

“Roy worked on the (rotary) concept for about three years before he came to us, and then we moved everything into our own facilities,” Hagglund says. “That became our basic crew: two fabricators, a draftsman, Roy and myself.”

As work continued, accommodations in the old service station were becoming cramped. Development of the rotary moved beyond building and operating stationary test rigs to creating a field-scale prototype.

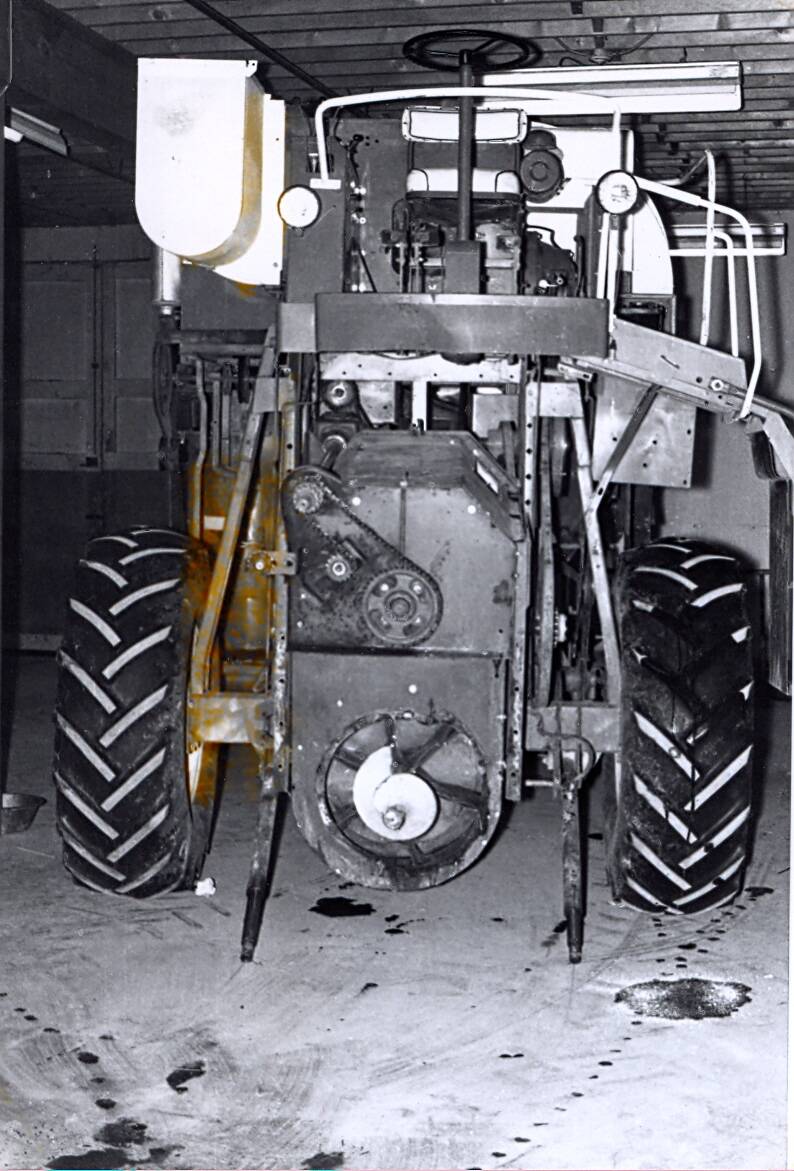

“We were in touch with Cockshutt all the time and Don McNeil, who was chief engineer and vice-president of engineering at the time,” says Gullickson. “He decided he wanted to do a full-size test rig. We did that at Cockshutt using a conventional harvester. In 1967 we took the cylinder, beater and straw walker out of it.” That prototype became known as the R1.

“We brought up a 535 (combine), which was a production machine,” Hagglund recalls. “We brought it up and stripped it out, took everything out of the inside. All we had left was a frame, drivetrain and engine. We took what Roy came up with, the thresher and separator part, and fabricated it in our shop. We used part of our central engineering facility to make parts.” The new rotary thresher and separation system were then installed into the 535.

But even though the team had to work on the prototype outside of its old service-station workshop, the company still wanted to keep a veil of secrecy over its progress.

“One of the contractors we had to make parts was making the rotor, which was fairly substantial and heavy,” says Hagglund. “He asked us what we were making, and I told him it was a cement mixer.”

To make for a simple installation, the rotor was attached directly to the feeder house. When the header was raised, the rotor tilted in unison with it. The pivot point between the feeder house and rotor was the 535’s existing feeder house mounts. There was no threshing advantage to this arrangement, it just made converting the combine to a rotary thresher a simpler process.

“We tied the corn head to the threshing and separating part,” says Hagglund. “It pivoted on a central pivot. That’s how we got the corn head to move up and down. We took it out into the field in mid-January to do corn.”

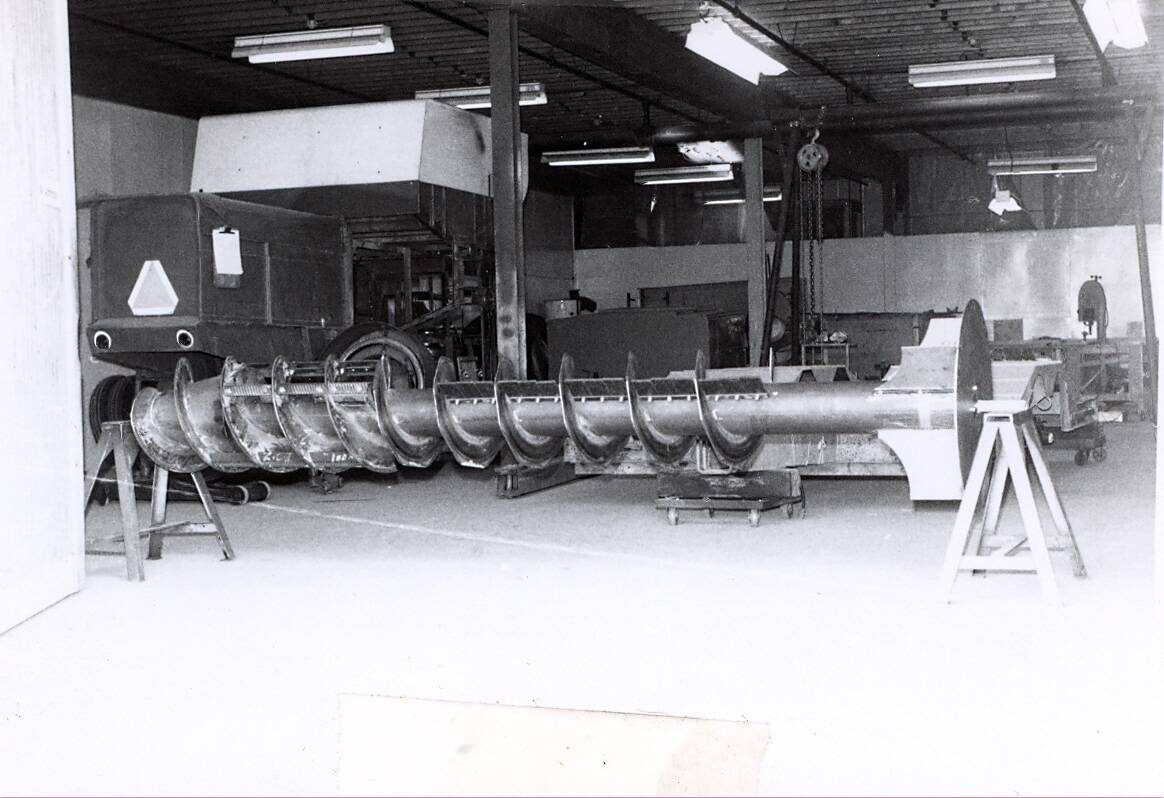

“The first rotor was about 24 inches in diameter,” says Gullickson. “It ran from one end of the combine to the other.”

Field goals

By the beginning of January the improvised prototype was ready for its first field trial, after being fitted with a two-row Oliver corn head.

But the team had been working on much more than just moving from a conventional, tangential threshing cylinder to an axial rotary design: the initial R1 prototype also included an entirely new vertical cleaning system. Grain was lifted up inside the combine body and fell through an upward airflow inside a rotating chamber that used centrifugal force to improve cleaning.

“The overall idea was we were trying to make a machine that was cheaper and easier to manufacture, because it had less parts,” Hagglund says. “By going vertical with the cleaning unit, we could harvest uphill, downhill or sidehill without any detriment to the cleaning.”

The method initially used to get material into the rotor was unconventional as well. “We started off with an air fan feeding material from the table to the rotor, but that didn’t work out well,” remembers Gullickson. “But the results doing corn, as I recall, were fairly satisfactory overall. So we decided to do a new combine design with the rotor part of the fixed structure of the combine.”

After the initial work in the field with corn, the engineers decided the second-generation prototype needed to be tested in cereal grains as well. To make the necessary changes to the prototype for that, White rented another, larger building in Brantford, and the small team moved from the old service station to the much bigger accommodations.

“We moved three times in the space of two years,” says Hagglund. “We didn’t allow anybody in unless they definitely had some reason for being there. We tried to keep it as quiet as we could.”

With the changeover to a grain header and the rotor fixed in place so it no longer moved in conjunction with the feeder house, the remodelled prototype, now designated the R1A, was ready for field work by mid-May of 1967. Then the team hit the road to Crystal City, Texas, to start field trials in cereal grains. Oats was the first small grain to be put through it. In 1968 another updated prototype, the R2A, was built on the 535 chassis and field tested.

Once the modified 535 combine had served its purpose as an initial test bed, it was time for a ground-up build to incorporate new and better design elements. Working out of its third rented location, the engineering team created an entirely new combine prototype in 1969. Designated the DE-1, it threshed with a 24-inch diameter rotor, took power from a Chrysler 440, V-8 engine connected to a hydrostatic traction drive and relied on a variable-speed belt to drive the rotor.

“The DE-1 was a totally new concept from the ground up,” says Hagglund. “Everything was built by hand.” By 1970 it was in the field.

The vertical cleaning system was also built into the initial DE-1 prototype, along with the rotary threshing system — but because the vertical cleaning system’s design had so many problems, it was eventually abandoned in favour of a conventional one. “We kept working on it,” says Hagglund. “The big problem with it was to make it adjustable and have it convenient to adjust. Cleaning is a very complicated game.”

Despite the fact the rotary team was making good progress, financial concerns at White necessitated belt-tightening measures that disbanded it in 1971. Both Hagglund and Gullickson left the company as a result. “People went in all different directions,” Hagglund remembers.

Regrouping

About a year later, management at White managed to stabilize the company’s finances and reallocate enough funding to the engineering department to restart the rotary project. But with the original engineers Hagglund and Gullickson gone, replacements had to come from the remaining staff.

Murray Mills was one of those selected to pick up where Hagglund and Gullickson left off. “I was working mostly on the conventional combines at that time,” Mills recalls. “We had the two groups within the combine engineering department, the small group on the rotary, originally, and the full-scale development on the conventional side as well.”

With new hands on the project, the top-secret approach gave way to a more inclusive effort after the restart in the early 1970s. “We started sharing (the work),” says Mills. “The way White’s engineering was at that time was there was an engineer in charge of engines, one in charge of frames and that sort of thing. There would be one engineer in charge of that (rotary) project, but he would have access to engineers in all the other groups.” That meant development of the rotary was now very much the combined efforts of the whole group of engineers.

That group did, however, reap the benefits of the major accomplishments from Hagglund and Gullickson: mainly, how they overcame much of the difficulty encountered in getting tough crop to feed into the rotor properly — a problem that lingered with the other brands’ designs, even after they began commercial production.

The secret to the White design was to add a beater in front of the rotor inlet to accelerate the speed of the crop mat as it came out of the feeder house — a system for which John Deere eventually purchased the patent, Mills says, and continued using a version of it on its combines.

Room for improvements

Once the NH and IH rotary combines hit the market, White’s engineering staff wanted to take a look at those designs, so the company purchased one of the first IH rotary combines and leased a NH to evaluate their performance.

Getting material to feed into the rotor and getting good straw distribution at the back of the combines were two areas where White engineers saw they could improve over those designs. Fortunately, they already knew how to get tough crop to feed in, thanks to Hagglund and Gullickson.

“Probably the two biggest things were the feeding and then the discharge from the rear end to make sure you get even distribution,” says Mills. “We changed the shape of the discharge at the back to get a decent spread of the material.”

The White engineers “developed a computer model and did a lot of work on the design of the rotor,” he says. “They were trying to move material with the rotor rather than with the guide vanes. It was almost like an auger, moving material with the rotor. That was never very satisfactory in a lot of crops. It was when they developed the guide vanes that things really started to look good. The original rotor looked like an auger with threshing elements on it.”

The computer modelling and the evaluations of competitors’ machines provided new insight for refinements to the rotor design.

“When New Holland introduced their rotary, it changed the direction we were going in, substantially,” says Voss. “We were working on an auger-flighting concept for a rotor. NH introduced longitudinal-type elements on the rotor and helical guide vanes.” The team at White realized it had to go in a similar direction as well.

With the final engineering obstacles overcome on the rotor, engineers were getting close to a marketable design — and that pleased White’s management, who saw rotaries as the way of the future. Even though a large, conventional prototype combine with a 60-inch cylinder, the model 9800, was nearly ready for production, management decided to abandon it. The weight of importance had shifted from conventional combine development to rotary.

“The decision was made to go with the rotary rather than a big conventional,” Mills remembers. “That basically stopped all development work on the big conventional under development at the time, because it was thought at that time that (the rotary) was the way things were going to go.”

“The original objective of the (rotary) project was to come up with a high-capacity combine, using technology that was different than what had been in use at that time.” adds Voss. “As a result it was a very demanding and huge project.”

Conventional cleaning

Another of the engineering casualties was the vertical cleaning system pioneered by Hagglund and Gullickson. “They had the idea they could go rotary on everything,” says Mills. “The cleaning system they were using was basically rotary as well. It was a vertical drum that was rotating. They tried to use centrifugal force to separate out the chaff. You could develop it to work well in one crop. The problem was, you couldn’t adjust it to change between crops. Screens on the vertical sections had to be changed. You couldn’t use the same screens in corn and wheat.”

So, the first White rotary combine would have to borrow its cleaning system design from the conventional models.

“There was a lot of energy expended on developing the new cleaning system,” recalls Voss. “We had to stop that when NH came out with the TR70. In hindsight, I think it slowed down the rotary development. It was too large a task for the number of people involved and the size of the department.

The first high-capacity prototype to be built using the modified rotor design combined with a conventional cleaning system was the HC-1. The rotor in the HC-1 was larger than previous prototypes, it grew to 80 cm in diameter and its length was extended. It was also the first prototype to use a rotor incorporating guide vane technology.

After further refinements, the HC-1 prototype morphed into the HC-2, which became the production version of the 9700. There were other HC prototypes as well. The HC-4 would become the smaller-framed 9320.

When all the research work was done and the threshing system design was market-ready, White originally intended to create three different-sized, self-propelled machines. The largest model, the class VI, 9700, would be built with the 80-cm, long-length rotor. A mid-sized, class-V 9400 (which was to get the designation 9520 for production) would get a smaller-diameter rotor the same length as the 9700s. And the 9100 (which would form the basis of the production 9320) was to get a shorter, 70-cm diameter rotor.

“We built two or three 9400s,” says Mills. “They were built experimentally but never put into production. There was nothing significant about it (in performance over the 9320) to give it any advantage. It shared the same body as the 9320. The 9320 was the simplest design. It had the fewest drive assemblies.”

Concluded and rebooted

In 1979 White began rotary combine production in Brantford, starting with the 9700. After some initial “clean-up” refinements, the 9700 was renumbered the 9720 in 1984.

But the financial situation for farm machinery manufacturers had become very difficult by the end of the 1970s. Low commodity prices and declining farm incomes in North America led to a sudden and significant drop in demand for combines.

White was placed in bankruptcy protection in September of 1980 and ceased operations five years later. The very first 9320s were just starting down the assembly line the day production was stopped.

Massey Ferguson purchased the White rotary designs from the bankruptcy receiver, giving it ownership of all the completed 9720s, any incomplete models on the assembly line including the 9320s, the parts stores and all the tooling required to build them.

Production of the 9700s then moved across Brantford to the MF facility. The 9320 Whites eventually made it all the way down the assembly line there wearing MF 8560 decals, while the larger 9700s were rebadged as the MF 8590.

Eleven years after serious engineering work began on creating a rotary combine at White, engineers finally saw their efforts begin to pay off with the model 9700s, which had the largest capacity of any rotary machine on the North American market when they entered production in 1979.

Unfortunately, the company would not last long enough to gain the full benefit of the efforts its engineers put into creating the new machines.

“For its time, the 9700 was a good combine,” Voss says. “It kind of pioneered the high-capacity direction machines have been forced to go in.”

CORRECTION, Jan. 23, 2026: The caption on the photo up top of Murray Mills and Neil Armstrong, as it appeared in the Dec. 31, 2025 print edition of Grainews, incorrectly identified Neil Armstrong as engineer Don McNeil of Cockshutt. The caption has been corrected here online.

Editor Dave Bedard — who really should have been able to identify Neil Armstrong in a photo — wrote the incorrect caption. He regrets the error and apologizes to Scott and to readers of the December print edition. – Dave B.