John Deere is typically remembered as a humble blacksmith who invented a better plow, which made life easier for farmers. He went on to found the company that still bears his name in 1837. Today the firm that started out in a one-man blacksmith shop is now the dominant agricultural manufacturer across the globe.

In all that time, equipment bearing his name has played an important role in the lives of millions of farmers worldwide. That has spawned a very large following of brand enthusiasts and individuals who have significant personal collections of the green brand’s memorabilia and equipment.

Deere too now has its own extensive archives containing not only select pieces of equipment but also items that detail its corporate history. The facility that houses that collection, which itself began in 1976, is located in East Moline, Illinois.

Read Also

Fall rye and oat nurse crops show mixed results for flea beetle suppression

University of Manitoba researchers are testing whether fall rye and oat nurse crops can reduce flea beetle pressure on young canola without hurting yield

“We were created because our CEO at the time, William Hewitt, the last Deere family member to serve in that role, commissioned a professor at Dartmouth to write a corporate history,” says branded properties and heritage manager Neil Dahlstrom, who curates the collection.

“So it really started as a corporate memory exercise. In order to do that, you need to start acquiring records and materials.

“We were fortunate in that we had what was called an agricultural library at Deere since at least the very early 20th century. They saved things like speeches, advertising and secondary market share research — even things like journals from Robert Tate, who was one of John Deere’s partners when he moved to Moline in 1848.”

Home to the Deere collection is a 75,000-square-foot building that houses millions of individual items. It was originally built as the East Moline sales branch in 1955 — so even the building is a piece of corporate history.

“We have the core archives,” Dahlstrom adds. “So it’s everything from business records to advertising to service literature, CEO papers, in the neighbourhood of probably three million photographs and a large film collection that dates back to 1929. In addition to that, there are several thousand artifacts — everything from stickpins from the early 20th century to licensed products, including toys and social media influencer kits most recently.

“We sample these things. We don’t collect one of everything, because there’s just too much. In addition to those, we also manage the company’s historical equipment collection, which is about 500 pieces. The oldest in our collection is a plow built by John Deere in 1853.”

There are milestone machines in the collection, including a 1980 4440 tractor, the two-millionth tractor to roll off the line at Waterloo, Iowa. It only has 27 hours on the tachometer. There are also combines, construction equipment and lawn tractors, as well as experimental prototypes that didn’t make it to production.

But not all of the collection remains stored in East Moline. Pieces from it are displayed at different times in 25 Deere locations across North America.

“We have 10 snowmobiles at the training centre in Grimsby (Ontario),” he says. “We’re designed to have large parts of our collection out on exhibit at any given time.”

Seeking specific artifacts

Dahlstrom adds he receives about six offers a week from people interested in donating or selling items to the Deere archives.

“We look at those things and balance everything from, ‘Do we have gaps in the historical record we need to fill? Is this a significant piece? Do we have space for it?’ That’s a growing concern — do we have somewhere to put it? The size of the equipment is making it really difficult. So I think we evaluate things differently now than we did 20 or 30 years ago.”

While the archive actively looks for specific items that fill those gaps in its collection, when those items become available, it often defers to individuals who would also like to add them to their own private collections.

“We also have the luxury of incredibly enthusiastic fans and collectors,” he says. “There are things we’ve passed on that have come up for auction, because the last thing I want to do is get something and put it in storage where no one is going to see it for the next decade. I’d much rather it be in private hands with someone who’s going to take it from show to show. We don’t need to own all of it.”

Among the items high on the archives’ wish list are early copies of Deere’s The Furrow magazine. They have a pretty complete collection from 1897 onward, but nothing earlier. The magazine began publication in 1895.

An example of a uniform of the John Deere Battalion from the Second World War is also being sought.

In that war, “the John Deere Battalion was formed from about 900 employees and dealer employees,” Dahlstrom says. “They served mostly in France and Belgium during the war. They repaired tanks, trucks, tractors and things. We have scrapbooks. I’d love a John Deere Battalion member uniform for the collection. Anything that personalizes who we are as a company I think is really important and significant.”

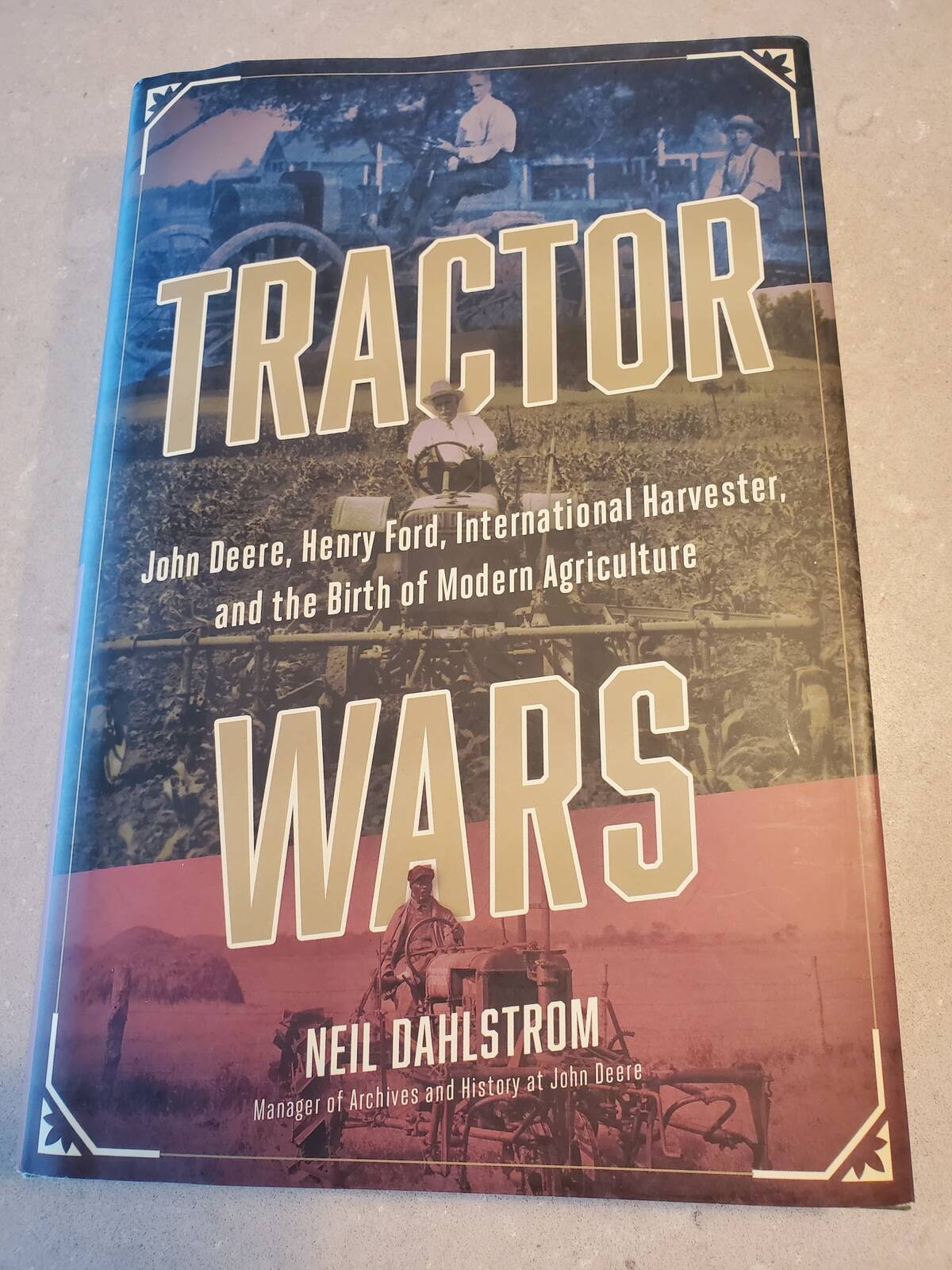

Dahlstrom is a historian in his own right and has published a book on the history of machinery evolution as farming moved from horses to tractors, including Deere’s role in it. He says after spending so much time detailing the history of the company founder John Deere and reading his personal papers and writings that others said about him during his lifetime, he believes he has come to know him.

“I’ve grown to know John Deere over my career here. We’re pals,” he says jokingly.

So would John Deere be surprised to find out that the company that bears his name today has become a global corporation with sales exceeding US$30 billion a year?

“I spent a lot of time thinking about this,” Dahlstrom says. “I think he wouldn’t be surprised … that is what set him apart from his competition. He built his first plow in 1837. In 1860 there were over 2,000 plow manufacturers in the United States alone.

“He survived that and evolved out of that for a reason. It’s because he had this constant focus on what we call continuous improvement today. By the time a competitor came out with something similar to him, he’d already moved on to something else.

“I see him as this guy who’s really enthusiastic about tech, which is really hard to put someone in the 19th century in that view. But I think that’s who he was.”