Herbicides have long been the go-to solution for Prairie grain producers fighting weed infestations. Over time, it has led to widespread resistance development in many weed species and a shrinking list of chemical options for controlling pervasive weeds like kochia and wild oats that have become resistant to multiple modes of action in recent years.

It’s a serious problem. And the answer, according to western Canadian weed experts like Breanne Tidemann and Charles Geddes, is to rely on not just one but multiple tactics to control problem weeds on your farm.

“Our herbicides, when they work, they’re the most effective, the most efficient and, in a lot of cases, the most economical. And we’re comfortable with them. We know how to use them, and we know how to use them well, and a lot of our other tools don’t have that same level of efficacy,” says Tidemann, a weed scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) based in Lacombe, Alta.

Read Also

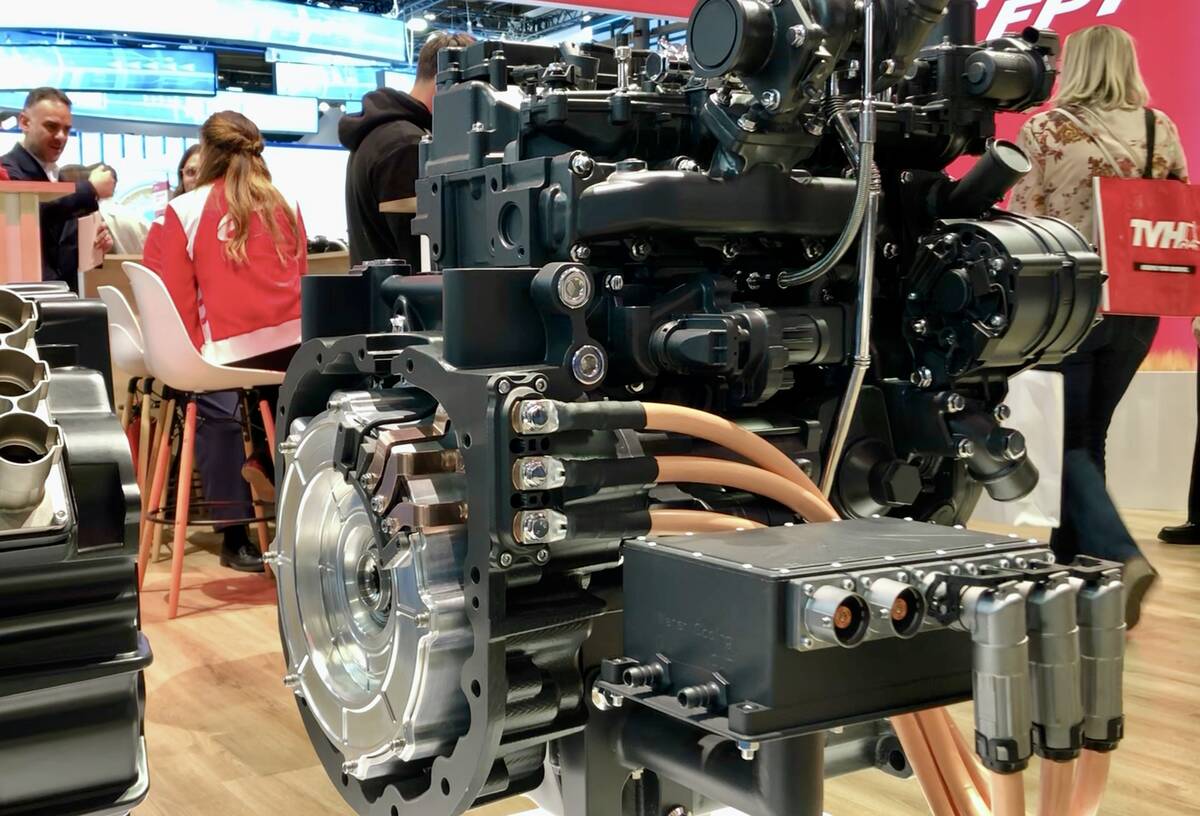

FPT showcases hybrid engines, modular battery concept at Agritechnica

Diesel engines have been the workhorse in agriculture for decades. FPT Industrial is one engine manufacturer that’s looking ahead to a post-diesel future.

As a result, she adds, herbicides have become an easy option for farmers. Both Tidemann and Geddes, who is an AAFC weed ecology and cropping systems research scientist in Lethbridge, Alta., view rising herbicide resistance as a warning bell that this way of thinking has to change.

Geddes says with more cases of weeds exhibiting resistance to multiple herbicides cropping up in Western Canada, it’s imperative that non-chemical approaches are more broadly adopted to preserve the efficacy of remaining herbicides.

“Herbicides have really been the easy button for decades now. And with greater selection pressure for herbicide resistance, we’re seeing greater amounts of herbicide resistance show up and impacting farms,” says Geddes.

“Essentially what that means is that button is degrading, and so moving forward, we do need to move in a direction that helps embrace complexity when it comes to developing a weed management program.”

Tidemann agrees. “If we really want to continue to sustainably manage our weeds, we’re going to have to leave the easy button behind and embrace a little bit more complexity to our management strategies,” she says.

“The more management strategies you’re using, the harder it is for a weed to respond to every single one of those. If you have a (resistance) response to one management strategy, then hopefully one of your other strategies can clean up after that and they can work together in that sense.”

Tidemann says an example of this is increasing seeding rates for certain crops, a form of cultural weed control that’s been shown to lower weed pressure in some instances by increasing competition from crops.

“I can’t necessarily say, ‘Go up your seeding rate’ and it’s going to work just as well as if you sprayed a herbicide. It doesn’t typically work that way. An increase in seeding rate can help suppress your weeds, but it’s not going to control them all on its own,” she says.

“But if you up your seeding rate and reduce the number of weeds that you have through that crop competition, and you’re still using an effective herbicide, now that herbicide is being applied to fewer weeds and this reduces the selection pressure for resistance to the herbicide,” Tidemann adds.

“Hopefully, that herbicide will last longer in terms of how long it works before you get resistance, plus you’ve got fewer weeds overall. You get the short-term benefit of using multiple strategies, which reduces your (weed) population, but you also get the long-term benefit of reducing the selection pressure from any of those strategies on their own.”

Tidemann stresses overreliance on any one control tactic, be it chemical, cultural or mechanical, can lead to selection pressure and eventual resistance development in weeds, which is why it’s so important to mix things up.

“Any single strategy that gets relied upon will select for resistance of some kind,” she says. “The classic example is barnyard grass and rice, where the management strategy was hand weeding the barnyard grass out of rice. Because of that selection pressure, there was a shift in the phenotype of the barnyard grass so that it essentially eventually mimicked the growth of rice. You couldn’t visually distinguish between the two species, which meant you couldn’t hand weed the barnyard grass out.”

Integrated weed management

Strategies like increasing seeding rates can be found within an integrated weed management framework, which is a broad-based approach that integrates both chemical and non-chemical practices for economic control of problem weeds.

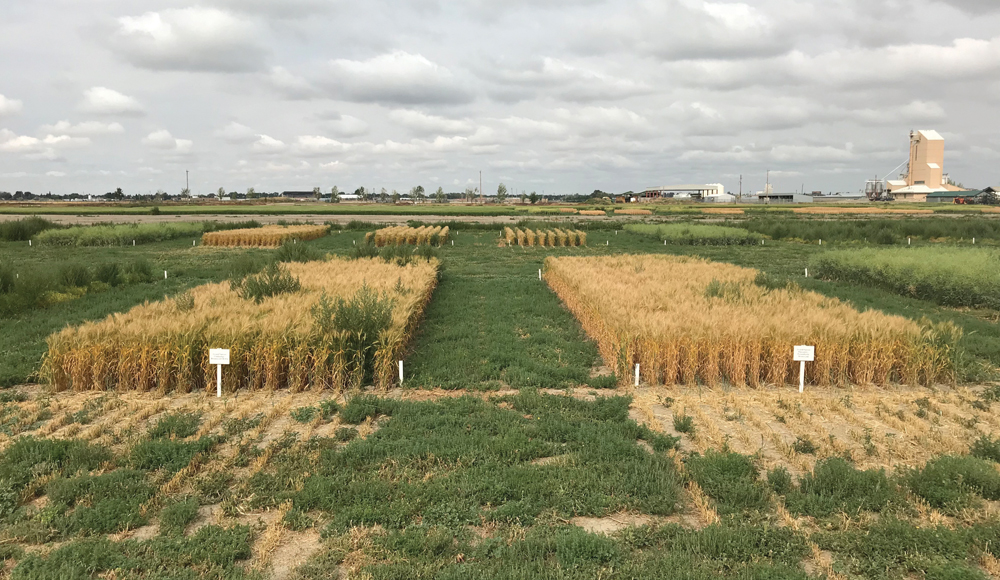

Geddes is currently wrapping up a study in Lethbridge, Alta., examining how adjustments in seeding rates and row spacings along with herbicide layering could be used together to help control kochia in a wheat-canola-wheat-lentil rotation.

The researchers found by using narrow row spacings and doubling recommended seeding rates and integrating this with a standard herbicide layering system, they could achieve an 80 per cent reduction in kochia biomass compared with using wide row spacings, recommended seeding rates and the same layering approach for herbicides.

Geddes is also studying how including crops with diverse life cycles within a rotation can also help control kochia.

“We’re finding that including a winter annual (like winter wheat) in your rotation actually really helps with kochia management because it’s already established and competitive when kochia is emerging in the spring,” he says. “Also, it’s generally harvested before kochia produces seed, so you can cut off those kochia plants and prevent seed from going back into the soil seed bank for that year, which helps keep the seed bank low.”

Geddes says crops grown in the Prairies vary in their abilities to compete with kochia and it mostly pertains to how quickly they close their canopies in the spring.

“A lot of research has found that within the range of crops, crops like barley, wheat and canola are quite competitive. In general, barley tends to be one of the more competitive summer annuals that we grow on the Prairies. Some lesser competitive crops often end up being some of the pulses, such as soybeans in Manitoba and lentils perhaps a bit further west,” he says.

Geddes notes growing cover crops can be an effective strategy for controlling weeds like kochia, but he acknowledges it can be difficult to do in parts of Western Canada due to moisture limitations.

“That’s often cited as one of the biggest challenges for cover cropping in the Canadian Prairies, especially in areas that are a bit drier and that’s really where kochia is the biggest issue. Under irrigation, certainly I think that cover crops would do well,” he says. “But the moisture limitation is one barrier when it comes to implementing cover crops efficiently.”

Because kochia thrives in no-till or minimal tillage systems, strategic tillage is sometimes suggested as an effective control tactic. Geddes says anyone considering it would be advised to look at it as one component of a larger strategy “where the occasional tillage pass might help, or perhaps targeting just the areas where kochia is the greatest concern.

“From a weed management perspective, tillage is one means of non-chemical weed control so there is potentially some benefit there,” he adds. “But when we talk about tillage, the thing that immediately comes to mind is what does that do to your soil conservation system? There are a lot of other implications regarding soil health that need to be considered in those decisions.”

Harvest weed seed control

Tidemann spoke about non-chemical weed control methods at the Manitoba Agronomists Conference held in Winnipeg last December, noting there is a lot of new technology available to farmers to help make their weed control efforts more efficient and effective.

This includes several innovations in harvest weed seed control, such as the Redekop Seed Control Unit (SCU) manufactured in Saskatchewan and the Integrated Harrington Seed Destructor, the Seed Terminator and the TechFarm WeedHog, all made in Australia. They are all physical impact mills that collect and pulverize weed seeds coming out in the chaff at the back of the combine.

“The goal … is to manage the weed seeds that are still in the field at harvest and prevent their dispersal,” Tidemann says. “Right now, when we take our combines through at the end of the field season, the weed seeds that are in there, most of them are coming right out in the chaff (and) we are broadcast seeding them.”

Geddes agrees implements for destroying weed seeds can be an important aspect of an integrated weed management system.

“Without some means of weed control at harvest, essentially your combine turns into a weed seed broadcaster, where a small patch (of weeds) can quickly turn into a big patch because it’s broadcast in the chaff portion that’s spread across the field. One of the big benefits of harvest weed seed control is that you might be able to limit it to that small patch without spreading it further,” he says.

Tidemann, who is currently collecting data on the efficacy of physical impact mills, says the cost for the physical impact mill units is in the range of $100,000. Even with the hefty price tag, Tidemann says she’s starting to see more of them on Prairie farms (from none five years ago to 20–25 that she’s aware of now).