Markus Weber answers questions about drones all the time. He is president of Landview Drones and he runs an Ag Drone School to help farmers get started with, and get the most out of, their drones. For less than $3,000, farmers can dip their toes into the drone arena.

“When they’re starting out, most farmers will start with a visible spectrum camera,” says Weber. “Largely, (those farmers) are driven by budget and by the fact that they don’t yet know what the capabilities of this equipment are going to be for their farm, or how they’re going to use that data.”

Read Also

Yield EyeQ camera system measures harvest loss at header

Harvest equipment manufacturer Geringhoff won a silver Innovation Award at Agritechnica for its Yield EyeQ camera system, meant to help farmers measure grain loss at harvest.

Weber suggests starting with a small, portable drone. “For most farmers, portability is going to trump everything else,” says Weber. “Very few of us carry our digital SLR cameras with us. We carry our phone around and use it because it’s there. I recommend people start with a small, portable drone unless they need a larger drone for windy conditions.”

Weber’s small drone package like the Mavic 2 Scouting Package, which has a Mavic 2 Zoom drone, extra batteries, carrying cases, landing pad and everything the farmer will need, starts at around $2,850.

“Having a bit of zoom is important for a farmer to be able to see a weed profile or ear tags,” says Weber. “For most, that will suffice for at least the first or second year. The drone itself will last four or five years, but if they’re making good use of it, they will want to upgrade at some point.”

The next level

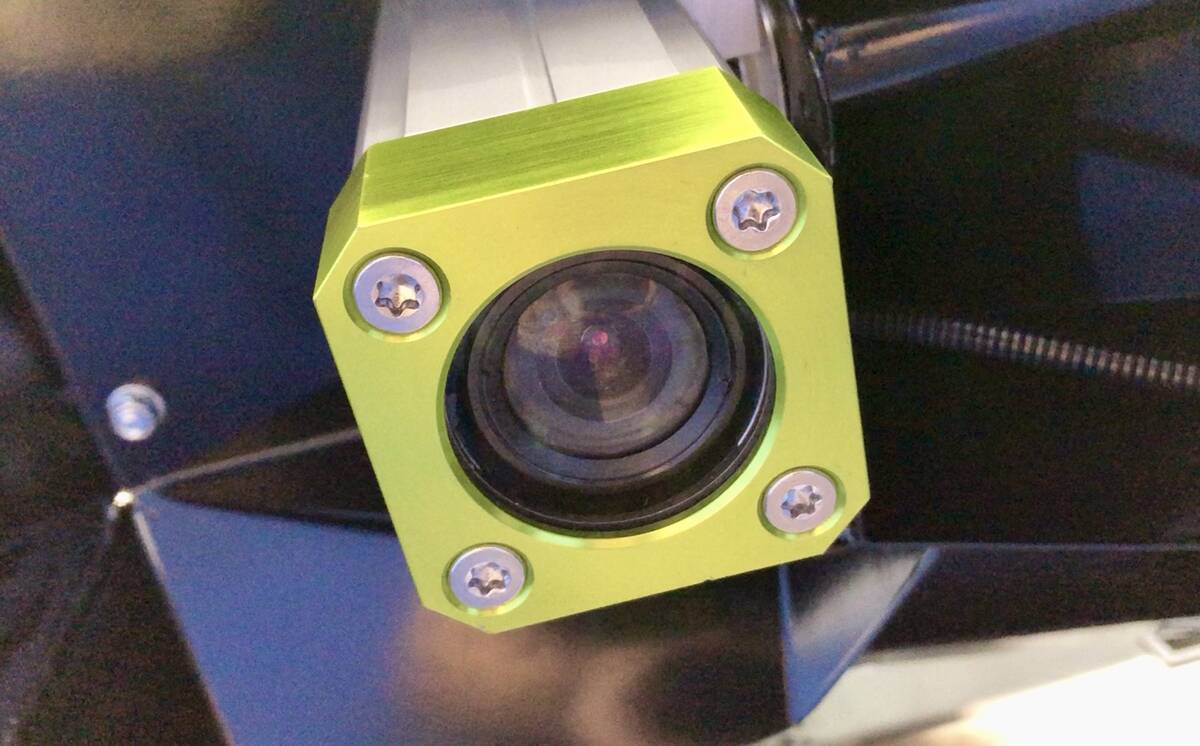

Once farmers begin to figure out how to map and create data, they will need to focus on the sensors more than the drone itself. “The sensor they buy will dictate what kind of a drone you can hang it under,” says Weber. “It revolves around what they want to see and what type of data they want to collect. The biggest upgrade is usually to go to a thermal camera for a livestock producer, or a near-infrared camera for a crop producer, and that doubles the price of the system.”

Professional drone systems can cost from $12,000 to $15,000, and will give incredible resolution — up to an accuracy of two inches. However, for most farmers, the data is where the magic lies. So, how hard is it for farmers to understand what their drones are telling them?

It’s not difficult at all, says Weber. “After two days, all the participants that come to our school will know how to fly a drone autonomously and how to collect data. The interpretation of these vegetative index maps comes naturally to farmers because they’ve all seen satellite imagery of their fields. This is like satellite imagery on steroids. It’s much higher resolution and timelier, but the interpretation is quite straightforward for most farmers who understand their fields.”

Farmers know their land best, so their drones are supplying another level of information to add to the other multiple sources they use every day. “Drones are part of a larger tool set,” says Weber.

“There is still going to be a lot of use of satellite imagery, but where I see drones fitting in is for the ultra-high-resolution imagery that you need sometimes. Satellite will never see the margin of a leaf or whether the cuticle on barley is attached or not. It’s that level of detail you can get from drones you can’t get from any other kind of imagery. This extremely low-altitude imagery is where I see drones still trumping satellite or manned aircraft.”

Your best resource: Other farmers

Surprisingly, there aren’t a lot of resources available for farmers to educate themselves about how to get the most out of their drones. The best resource is often other farmers.

“I’ve got a section of our course called 101 Uses for Ag Drones. I have gone past 100 largely because I’ll have other customers come back and say, ‘I figured out another way I could use my drone.’”

As much as farmers are the best resource for other farmers, the problem is they don’t always have a way of connecting.

“I find the biggest benefit of our school is they spend two days with other like-minded farmers from the area. Then they continue that conversation and continue learning together because there isn’t a comprehensive resource anywhere that will teach them all these ways of using their drones,” says Weber.

The future of on-farm drone use

Weber believes there will be more drone use in the future for things like cover crop applications or small-scale herbicide or pesticide applications for targeted areas.

There has been rapid adoption of drones on farms, especially for crop scouting and livestock monitoring; however, for data collection and creating georeferenced maps, uptake has been much slower because the industry, to date, has focused on producing a better drone, not necessarily producing better sensor analytics, he says.

“There are a few companies that have improved the analytics, but we’re still far from getting a Canada thistle map automatically out of a drone,” says Weber. “We get an NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index) map from which we can then infer there’s probably thistles, if that’s flown at the right time of the year, but it’s not providing immediately actionable information. That is the biggest barrier to large-scale adoption.”

Eventually, predicts Weber, these evolutions will come. “What we currently have for systems is a combination of robotics, aviation, remote sensing and spectral interpretation. What we didn’t have to date was machine learning,” he says. “I think that artificial intelligence and the wealth of spectral data we can already get about crops will lead to better, more automated analytics, so we can get a map of a specific weed. That is immediately actionable to a farmer.”