Regular readers will recall my earlier columns – ‘A snow job: Part 1‘ and ‘A snow job: Part 2‘ – dealt with snow as a contributor to 2021 crops. This year has been a major learning curve for me on the possible benefits of snow to grow a crop.

My dad always said, “Give me an inch of rain on Les’s birthday (July 7) and keep all your snow.” Over the years on my Dundurn farm, snow has made a mess of the farmyard and filled sloughs with water, but added little to subsoil moisture. This year that was not the case.

Read Also

India likely to triple lentil import duty

Analysts anticipate India hiking duties to 30 per cent after March 31 to bolster domestic prices on expectation of strong harvest.

At the Dundurn farm at freeze-up 2020, the soil was bone dry to three feet with only a bit of available moisture at greater depth. That means enough precipitation had to be received to fill up the top three feet to field capacity before any of the deeper moisture is of any use to plants. The chances of that happening seemed remote.

Enter a huge snow and blow in early November 2020 — and that on top of bone dry soil. In the farm garden, a 10-foot observation well has been dry for the past two years and I could not get the soil probe in the ground anywhere last fall.

The big November snow packed in several feet of very dense snow containing lots of water. That all melted and went straight into the ground. The observation well had water very close to the soil surface right after snowmelt and settled at about four feet in May. The soil probe went in the ground like butter anywhere in the garden.

Spring soil probing in the field showed reasonable soil moisture wherever the snow packed in for a significant depth. In rolling land that can be dimples in the landscape at fairly high elevation. The fact that the soil never froze meant all snowmelt went straight in. Technically, soil temperature would have been below zero Celsius but there was no moisture to freeze to block entry of spring meltwater.

Spring soil probing in the field showed reasonable soil moisture wherever the snow packed in for a significant depth. In rolling land that can be dimples in the landscape at fairly high elevation. The fact that the soil never froze meant all snowmelt went straight in. Technically, soil temperature would have been below zero Celsius but there was no moisture to freeze to block entry of spring meltwater.

For the 2020 crop, we had six inches of well-timed rain in May, June and July and harvested a fair crop. My garden patch did not have sufficient subsoil moisture and despite liberal watering over the row it was a struggle to get a decent crop.

In fact, it was the poorest I have had in the 20-plus years at that site. In 2020, despite row watering and no excessive temperatures, temporary wilting was observed often in most crops in midday with much cooler temperatures than 2021.

In 2021, despite many long, hot days, I have observed no wilting of the biggest leaves even in mid-afternoon with temperatures as high as 36 C. The rows in the garden are 10 feet apart. Roots grow down several feet but also grow out a few feet. It takes subsoil moisture to accommodate those lateral and deep roots.

Enough about the garden patch, what about the wheat field?

Meanwhile, out in the field, I now have the land rented and the renter seeded wheat on May 5 with excellent seed placement. And except for the high knolls, it came up very well and made a good stand. After the May 24 rain, there were some winter annual weed patches but a timely herbicide application took care of that.

On hilly land, most years when trying to decide if a wheat field was ready for the combine, we would go to the low areas that tended to stay green after the rest of the field was ready. This year it is exactly opposite. The best crop, in areas where snow accumulated, germinated and emerged quickly and has matured quickly. Soil temperature was high very early in the season.

The areas with the green kernels at the time of writing (August 6) are on the high knolls instead of in the low areas. When it was seeded May 5, even deep seeding did not catch enough moisture on the high knolls to allow good germination.

Some seeds germinated and died before they could set down roots. The remainder of the seed germinated and came up after the May 24 rain. That reduced the plant population to what was optimum for the moisture conditions this year. Those plants have good heads with plump kernels. It is well worth waiting a few days to let those kernels ripen and dry down.

Water use by plants

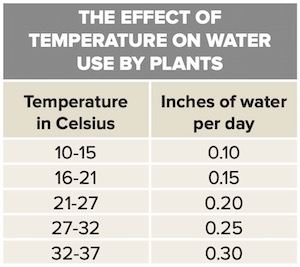

When in the grand period of growth, usually about mid-June to late July, a crop will use the following number of inches of water per day, depending on temperature.

On those real hot days this summer, an inch of water would only last three days. The data shown in the table and related information is from page 113 of Henry’s Handbook. I took that data from a North Dakota bulletin.

This year has been a real learning curve for me and proves once again — in farming, every year is different and the learning never ends.

In closing, I wish to pass on a special thank you to our Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation who moved quickly to make it possible for stubble jumpers and cowboys to work together to do as much as possible to provide feed for livestock. There are examples right in our area where that has already taken place. Poor cereal crops are being baled for feed.

In the September issue of Grainews, we will look at droughts from years gone by. At my advanced age I have lived through several of them. Have a safe harvest and we hope for better things next year.