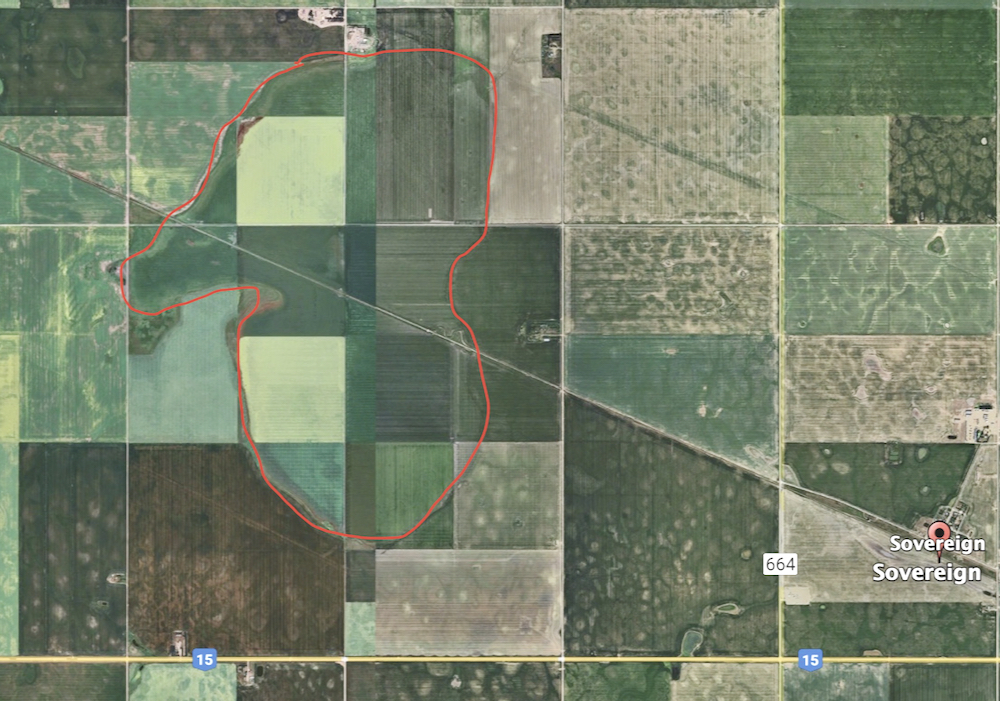

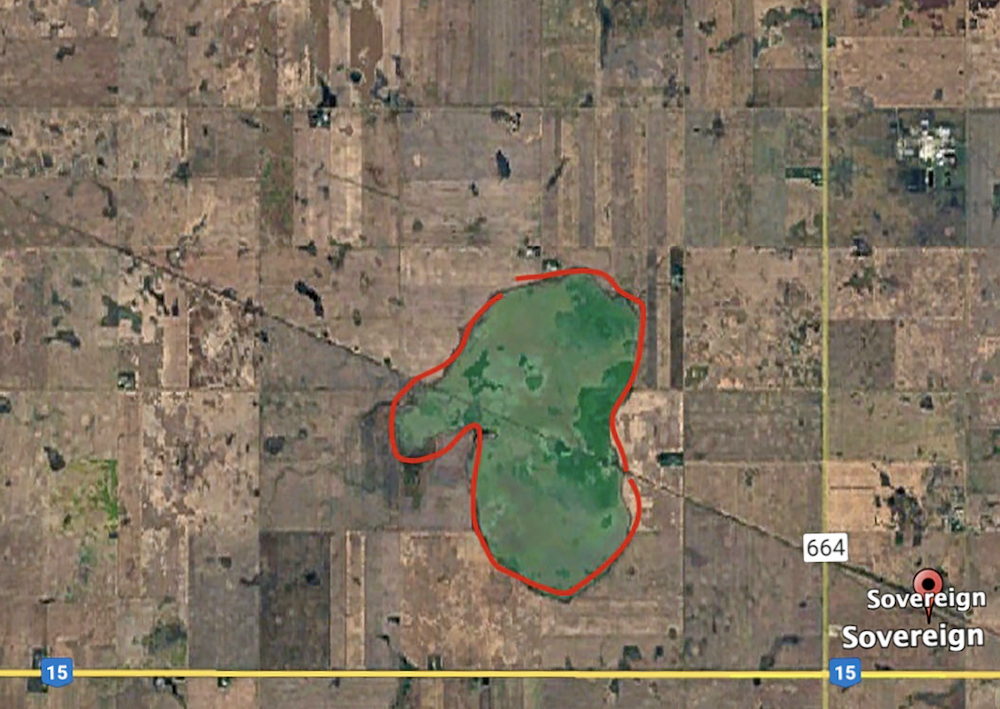

Sloughs (polite name is potholes) are widespread on the Canadian Prairies and particularly in Saskatchewan, which has a great depth of glacial deposits. The sloughs catch much of the snowmelt and runoff from summer rains. If the water in the slough is the sole cause of salt rings, then all sloughs should have them.

Artesian pressure from beneath is the main cause of salt rings. Deep drainage by a deep aquifer that drains to a creek or river is why some very large sloughs have no salinity.

I checked out municipal assessment and they assess the land as normal and then take a 50 per cent deduction for poor drainage — assume crops will be five years out of 10.

Read Also

Avoid these thought traps when investing

Investing for Fun and Profit: Let’s review a list, by renowned fund manager Peter Lynch, of the most dangerous things that stock market investors can say to themselves, or to others.

But what is the deep drain that allows all of this to happen? The deep drain is the pre-glacial (bedrock) Judith River aquifer. In that area, the wells completed in the Judith River Formation are 500-plus feet deep, and the static water level is 100-plus feet below ground surface. The Eagle Creek is about 12 miles north of Sovereign and the Judith River aquifer discharges to Eagle Creek.

In the decade or more of high profits on farms (approximately 2005 to 2019), there have been many Judith River wells completed in that area. With current drilling and well completion methods, yields of 20 gallons per minute or more are common. The water is mineralized but it is soft water (sodium dominated), which is great for domestic use.

Testing Eagle Creek

Eagle Creek drains to the North Saskatchewan River about 15 miles west of the Ag in Motion site, west of Langham, Sask. Several years ago, I used my trusty water electrical conductivity meter and Hach Hardness Kit to test Eagle Creek water that was flowing despite a long, dry spell.

Creek water that has water from glacial deposits is hard. We checked several locations from Asquith to the point Eagle Creek discharges to the North Saskatchewan River. The water was too soft for glacial deposits and that indicated discharge from the Judith River Formation was occurring.

So, there you have it. To understand our soils, we must also understand the geology beneath our soils. Water is the elixir that ties the two together, so we must understand the groundwater also.