Years ago, I took one of my first beef marketing courses from a professor who wore a clean white lab coat to class. There was nothing wrong with that, but his previous class was a red meat-cutting class.

One of the first thing he taught us is how to determine background-feeding profit. If its expenses — mainly the cost of the calf and cost of feed to bring it from 400 to 700 pounds is less than the sold calf revenue — a profit is enjoyed. If not, a loss is incurred. Today, this goal for profit still rings true, taking into account a list of new costs that were unheard of back then.

Read Also

Get ready for an eventual transition on cattle traceability

When new federal cattle traceability rules do ultimately take effect, reporting requirements will vary for producers, transporters, feedlots and markets — but most of the onus will be on producers.

Another thing that really hasn’t changed in nearly half a century (wow) is that “backgrounding feeding programs” means different things to different people. Recently, I reviewed a number of market articles about value of feedlot-bound yearlings that have come off grass. This background situation differs from a producer who might calve his cow herd in the late spring, creep-feed their nursing calves during the summer and then overwinter weaned calves in drylot to be sold in the new year.

I find that most beef producers who background their cattle (grassers and late calvers, included) fall into three general categories:

1. Small-framed calves to be overwintered on all-forage diets to gain about 1.0 to 1.5 lbs. per head per day. They will most likely be returned to pasture during the next grazing season. Yearlings weighing over 750 lbs. and taken off pasture might be put onto growing/finishing rations in the feedlot.

2. Lightweight calves that gain 1.5-2.2 lbs. per head per day on all-forage diets, which might be supplemented with medium-energy byproducts or limit-grain fed. These calves might be returned to pasture or go onto a feedlot. This class could also include late-spring calves that are backgrounded all fall/winter and sold to a feedlot early in the new year.

3. Medium- to large framed calves that gain 2.0 -2.5 lbs. per head that are put on a high-plane of nutrition in a feedlot. This class may include December/January born calves with heavy weaning weights by fall.

A backgrounding example

A friend who operates a 400-head Angus-Simmental cow herd that calves in late spring is a good case study for option #2. All calves are weaned in mid-October. They pull out about 35 replacement heifers and the rest are backgrounded until the middle of February. He Usually sells the steers first and the heifers a couple of weeks later. For the first time in a decade, this year he is considering selling all weaned calves by November 1, for two valid reasons; 1. forage inventory is tight due to local drought, and 2. future backgrounding profits are risky.

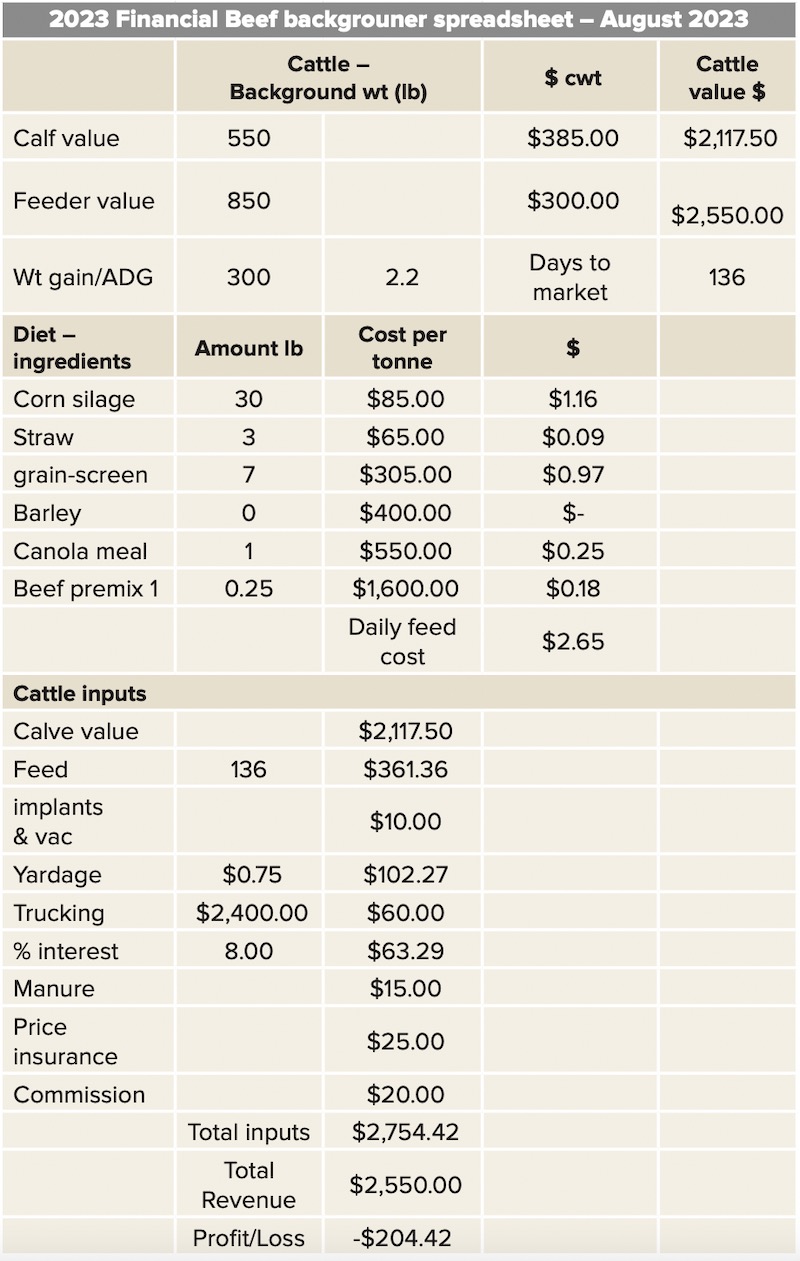

To help him make an educated decision, I created a balance sheet to determine the profitability of feeding his steer calves from autumn (2023) to be sold next February (2024). The main parameters of his backgrounding feeding program follow:

- Weaned 550-lb. steer calves are brought to his home drylot (re: backgrounded 475-lb. heifers are on a similar but segregated program) and raised to 850 lbs., when they are sold.

- Backgrounding diets are based on feeding corn silage as a forage base, heavy screening pellets for supplemental energy, canola meal for protein and a well-balanced mineral-vitamin premix with monensin. Estimated ADG is 2.2 lbs per head daily, which keeps them in the drylot for 136 days.

- Commodity prices are based on the current markets. Expenses associated with yardage (labour and fuel), trucking and manure cleanout are similarly taken, but from local sources. Financial costs such as interest on bank loans, livestock insurance protection and commission are tailored to this operation.

- Saleable revenue of 550-lb. weaned calves as well as backgrounded 850-lb. animals are taken from the current livestock trade in Western Canada. For illustration purposes, this is a straightforward transaction of cattle at the time of sale.

Costs exceed revenue

In this real-life case, the expense of putting on 300 lbs. of saleable weight on these steers is higher than the revenue brought-in by these 850-lb. backgrounders. Notably, $200 is lost per sold calf. At face value, this producer is better to sell his all his spring calves (assuming backgrounding heifers fare no better) within weeks after this autumn’s weaning season.

His situation is not unique, but a current state of affairs in the backgrounding industry. To test my conclusion, I substituted in some reasonable yet lower input costs in the same spreadsheet, and the result did not significantly change. That’s because the input values of most feeder cattle are at historical highs, coupled with the high cost of feeding them. Plus, there are high non-feed costs such as high yardage and finance costs that were not even imagined four decades ago.