Interest in spot sprayers has continued to grow among western Canadian farmers over the past decade.

It’s easy to understand why. Spot sprayers can detect and spray a weed, leaving a crop untouched, and can dramatically reduce the use of expensive chemicals thanks to a combination of artificial intelligence, machine learning and state-of-the-art sensors.

While recognizing the advantages is easy, determining whether they will pay off on the farm can be far more complex, says Tom Wolf, a spray application specialist based in Saskatoon.

Read Also

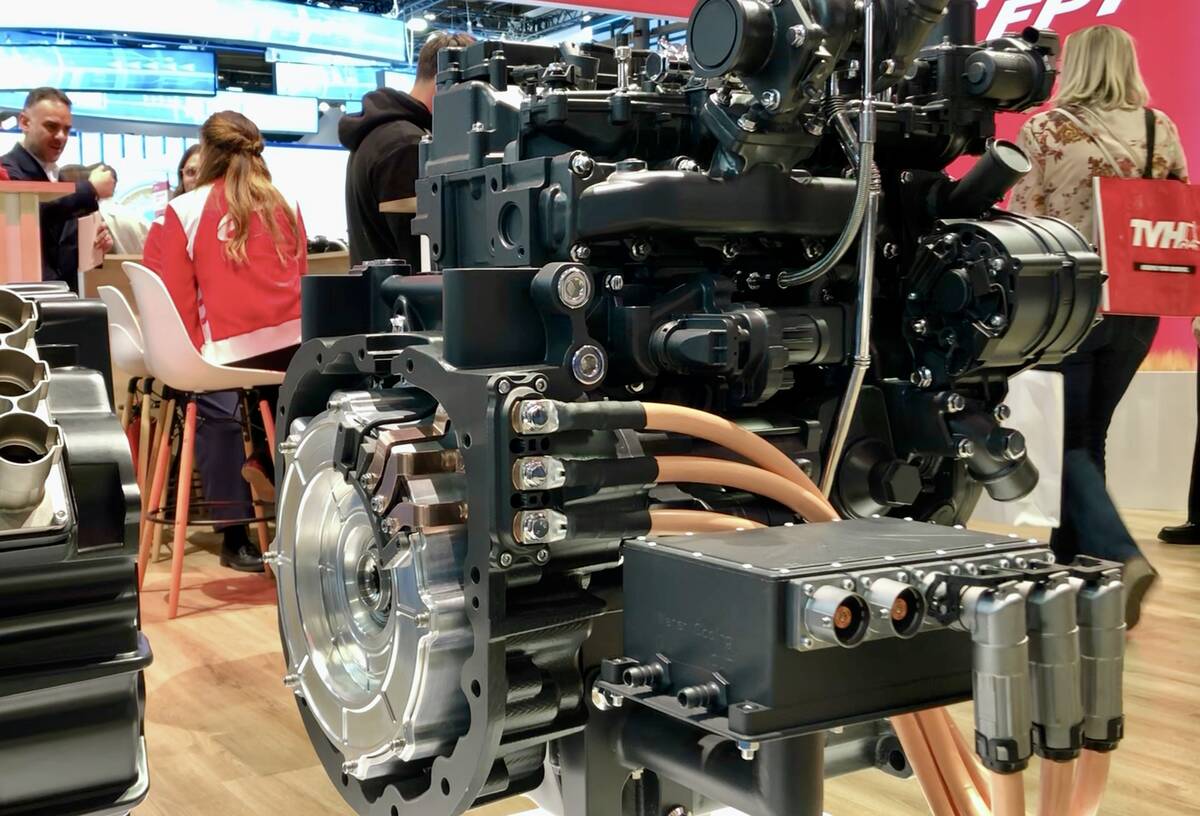

FPT showcases hybrid engines, modular battery concept at Agritechnica

Diesel engines have been the workhorse in agriculture for decades. FPT Industrial is one engine manufacturer that’s looking ahead to a post-diesel future.

That’s especially true when it comes to green-on-green sprayers, which can detect weeds within a green crop and selectively spray them. Although these sprayers have great promise, Wolf says they may not be a great fit for everyone.

Many green-on-green systems that are commercially available charge some form of user fee for the detection algorithms used in their software package. These fees typically range between $3 and $4 per acre and are either applied once per season, regardless of how many times the algorithm is used on a specific field, or each time the system is utilized.

No such fees are charged for green-on-brown systems.

Wolf likens these machines to inkjet printers. While the hardware can be relatively affordable, the manufacturer generates ongoing revenue by charging a user or subscription fee. That can make it more difficult for a producer to determine the return on investment for these sprayers.

To illustrate his point, Wolf uses an example of a herbicide that costs $5 per acre to apply. By using a green-on-green sprayer, a producer can save perhaps 70 per cent of that, so the cost to spray is now only $1.50 per acre.

However, if they have to pay an algorithm cost of $3 per acre, their total cost jumps back to $4.50 per acre, netting a savings of just 50 cents per acre.

Econonic sense

“The issue is that every single company wants five bucks per acre from the farmer for something or other,” says Wolf, who is also co-founder of the website Sprayers101.com.

“Farmers literally have a hundred different ways to pay someone $5 per acre, so they’re going to have to pick and choose which one makes economic sense.”

Another factor to consider is green-on-green sprayer accuracy, Wolf says. For example, what does it mean if 10 or 20 per cent of the weeds in a field go undetected? Is it better to do a second pass, which increases costs? Or risk a loss in yield that could reduce profit?

“This is something we’ve never actually thought too much about before because our broadcast herbicides have been so good, frankly. They’ve produced very reliable results. They’re a proven technology.”

Wolf says the decision to use a green-on-green sprayer could come down to a producer’s familiarity or comfort level with the algorithm it uses.

“A very mature algorithm that you’ve come to trust and you’ve used a lot and works well with an expensive herbicide, it’d be a no-brainer, you’d use it. But an experimental algorithm in a difficult situation which is mission critical for the success of your crop, maybe you wouldn’t.”

Lots to consider

Because the technology in some spot sprayers is still new, ROI isn’t the only consideration when it comes to deciding whether to use it.

Wolf says many of the customers he has spoken with are early adopters of new technologies. They look for items that line up with their personal values and philosophies.

“These are the people who say, ‘I just want to invest in this and learn with it. It doesn’t have to pay for itself right away.’ They’ve kind of seen what AI has been able to accomplish in other walks of life and are saying ‘I think I want to grow with this technology.’ It’s a philosophical decision.”

Regardless of whether it’s green-on-green or green-on-brown technology, Wolf recommends investing in a sprayer with both spot spray and broadcast modes of action.

Broadcasting at a low rate in addition to spot spraying can dramatically reduce the survival rate of small weeds while also protecting yield.

He also suggests that producers consider the types of crops they will be spraying and how sensitive they are to herbicides.

For example, lentils are a high value crop but are remarkably non-competitive early in their growth stage. A grower can’t afford many misses during spraying and also can’t risk herbicide damage.

On the other hand, spring wheat is an ideal candidate for spot spraying because it emerges vigorously and tillers quickly so there is less risk of herbicide misses.

Wolf says it’s important for producers to understand that there is no quick or easy way to determine the savings that could be realized using a spot sprayer.

“You don’t know those in advance, you only know your savings retroactively. You can’t budget for savings,” he says. “You have to become a little bit experienced with the system to know how it’s going to pan out financially.”

Reinvesting in the future

Regardless of savings from spot sprayer use, Wolf urges growers to consider reinvesting at least part of it into their tank mix.

Putting money into additional modes of action is an investment in the future — one that can delay the onset of resistance problems, he says.

“I would say resistance is perhaps the gravest threat we face (in agriculture). It’s a slow-moving threat. We get used to it because it’s only a few per cent worse each year, but resistance never gets better.

“Farmers are forced by virtue of their business to think annually in terms of their profitability, to pay the bills. But we also have to look generationally at our fundamental problems.

“We do that with regards to soil conservation. We think long term. We know that a small amount of erosion every year ends up being a lot of erosion over a generation, so we don’t accept any.

“We have to think along the same lines with resistance. It is a small change every year, but it only goes in one direction. It only gets worse.”