Standing in a demonstration field at the Ag in Motion farm show near Saskatoon in July, Markus Weber, president of AgEagle Canada (AgEagle.ca), launched one of the company’s unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as the Grainews video team looked on. The battery powered, flying-wing model quietly took to the air and flew the preplanned route Weber had programmed into it from a tablet a few minutes earlier.

Designed for agricultural field mapping, the flying-wing configuration allows the AgEagle UAV to cover a lot of ground in a short time.

“The AgEagle is our flagship product, 250 acres in 35 minutes,” he explains. “So it’s large acreage coverage.”

The company sells another type of UAV too, the multicopter. Each of the two models has different advantages, but Weber thinks it’s the fixed-wing AgEagle that will be the most in demand in agriculture.

“For most farmers, this is what I think they’ll be buying, eventually,” he adds. “For entire fields, you’re going to use something like that. There is incredible complexity in there. There is WiFi onboard. There is a cellular modem. It’s communicating with the cellular network to send imagery live while it’s flying.”

With its onboard Sony QX1 or A5000 camera, the AgEagle can take photos and provide the pilot with a “fully stitched” image where all inflight pictures are merged together into full-field displays. The images can then be transferred to a farm office or sent to an agronomist. And the cameras are NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) capable, allowing you to get a good understanding of the growing conditions in a field.

“The imagery you’re collecting with our machines, by and large, is NDVI,” he says. “People are working on hyper spectral and thermal. There are a whole bunch of different optics that are available, but the most common is NDVI.”

“You could use it as early as before seeding to see where you have weeds. You could fly digital elevation models in the fall as well. 3D modelling, all this kind of stuff is available as well. So you can use it early and late in the season, but most of it is going to be during the two to three leaf stage, which is about the smallest (plant size) you’ll be able to see from an altitude of 300 to 400 feet.”

Read Also

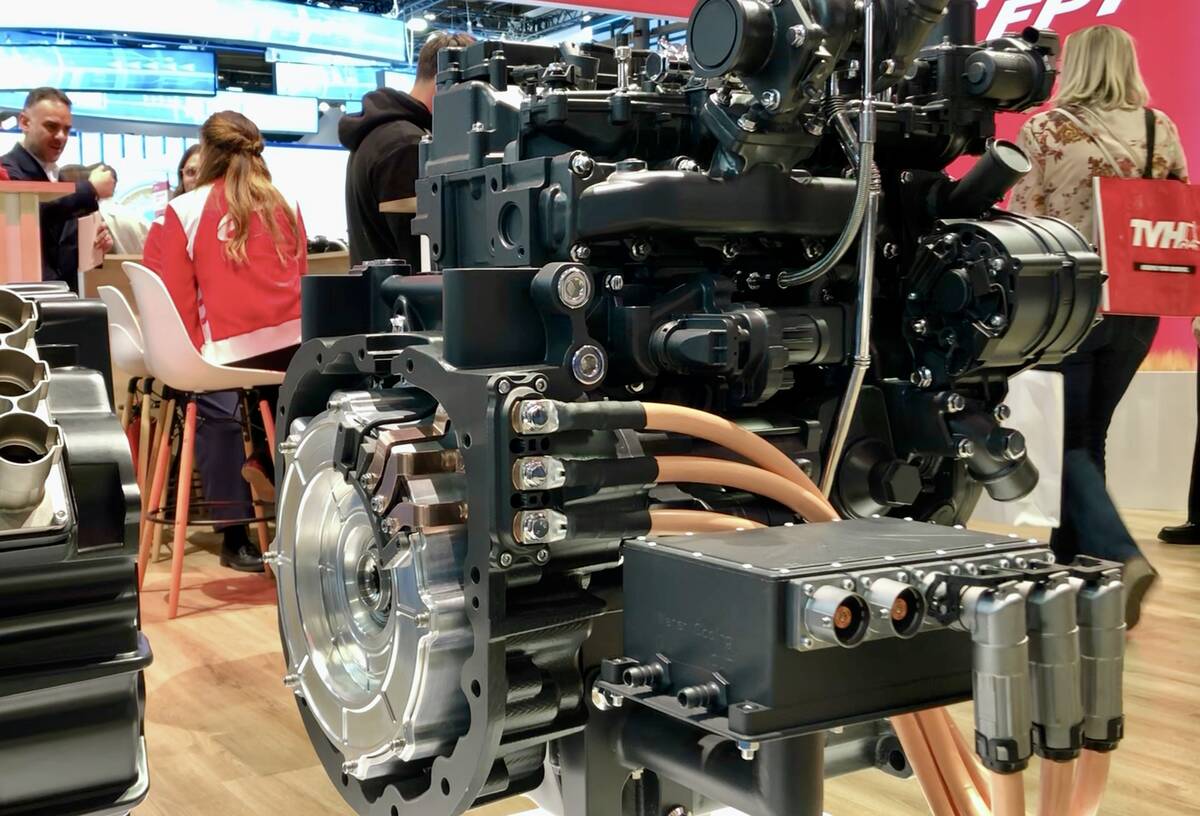

FPT showcases hybrid engines, modular battery concept at Agritechnica

Diesel engines have been the workhorse in agriculture for decades. FPT Industrial is one engine manufacturer that’s looking ahead to a post-diesel future.

The company’s other model, the multicopter, has the flight characteristics of a regular helicopter, enabling lower-level flying and hovering, which farmers could use to obtain more localized, close-up images or do any of a variety of other photographic tasks. Although it looks like a more expensive machine, the multicopter is actually a cheaper alternative, with a price tag starting at about $6,450 compared to roughly $20,000 for the fixed-wing AgEagle package. But both come with all the equipment necessary to start collecting on-farm data right away.

“This one (the multicopter) is better tailored to flying different altitudes,” Weber continues. “With a flying wing you have a certain speed you need to maintain or it stalls out. You’re flying 33 m.p.h. You’re not going to go lower than 300 feet, generally. If you want an up-close look at some plants, you’re going to have to use a helicopter of some sort.”

The multicopter has a shorter flight time, however, 18 minutes in the air compared to 35 minutes with the flying-wing model. That’s because the wing provides the lift, and the propellor only has to move it forward.

“The principle is rather than using energy to keep it aloft, like a multicopter, you’re using energy to drive it forward,” Weber explains.

While UAVs provide a unique method of collecting on-farm data to help in management decisions, Weber notes that farmers will need to have a firm idea how they will use the avalanche of new information they’ll be collecting before making the investment in a UAV.

“The main thing they need to know is how they’re going to use UAV imagery on their farm,” he says. “Most people don’t know how they’re going to use the NDVI imagery yet. The flight platform is the delivery vehicle, but ultimately it’s about the camera, taking pictures with that camera and turning it into data they can really use, either to make decisions or figure out if the decisions they made, made sense.”

“In Western Canada, the uses are quite creative. Once they buy them, it’s amazing what people use them for.”

Weber cited an example of someone who used his UAV to make multiple passes above a field over time to see if a fungicide application during dry conditions made any difference to the crop.

“He spent $25 per acre to spray and didn’t see a difference,” Weber says. “He didn’t save the money this year, but he sure will next year.”

For a video look at the AgEagle flying wing and multicopter, go to e-QuipTV.