Climatic constraints such as a short growing season or too little fall moisture are often given as reasons why cover cropping may not be a great fit for the Canadian Prairies.

A recent farmer survey, though, shows many western Canadian producers are making cover crops work, and are benefitting in ways you may not have imagined. The survey also suggests it is a lack of agronomic knowledge and support — and not only climate — that may be preventing more Prairie farmers from giving cover crops a try.

Callum Morrison is a University of Manitoba graduate student who works as a crop production extension specialist for Manitoba Agriculture in Carman, Man. The Prairie Cover Crop Survey is part of Morrison’s master’s degree thesis, which is examining the state of cover cropping in the Canadian Prairie provinces.

Read Also

PMRA denies strychnine emergency use request

Emergency use of strychnine for the 2026 growing season has been denied by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency.

Yvonne Lawley, an assistant professor in the department of plant science at the University of Manitoba, supervised Morrison’s cover crop project and delivered a presentation about it at the Manitoba Agronomists Conference held in Winnipeg last December.

The farmer survey was a fundamental piece of the project. It provided some key insights into why early adopters on the Prairies are growing cover crops, where they’re doing it, how they’re doing it and what they’re getting out of it. It also shed some valuable light on what is hindering acceptance of the practice among farmers.

A total of 528 farmers participated in the survey. Of these, 281 grew cover crops in 2020, the year the survey was taken. Cover crops were planted as a shoulder season (fall) cover crop, as a full season cover crop, or a combination of both.

The total area where cover cropping was practiced was 102,500 acres. Shoulder season cover crops were grown on 55 per cent of these acres and full season cover crops on the remaining 45 per cent.

The cover cropping farms were split into two categories: one “grazing” group, where cover crops were used as forage for livestock and also to assist cash crop production in some cases, and another “non-grazing” group, where cover crops were not used as forage for livestock.

Morrison says this was done to provide more insightful analysis of the survey results, since the two groups tended to differ not only in their reasons for growing crops but also in the methods and types of cover crops used.

In the interest of brevity, this story will focus on survey data that most pertains to the group of non-grazing farms where cover cropping was practiced.

Where are farmers cover cropping?

Lawley says she was thrilled more than 500 farmers participated in the survey, and she attributes that number to Morrison’s hard work, smarts and social media acumen.

“He is the reason it was a smashing success,” she says. “I think I told Callum at the beginning of the project I was hoping we might hear from 50 farmers, and then we heard from hundreds. It was beyond my wildest dreams.”

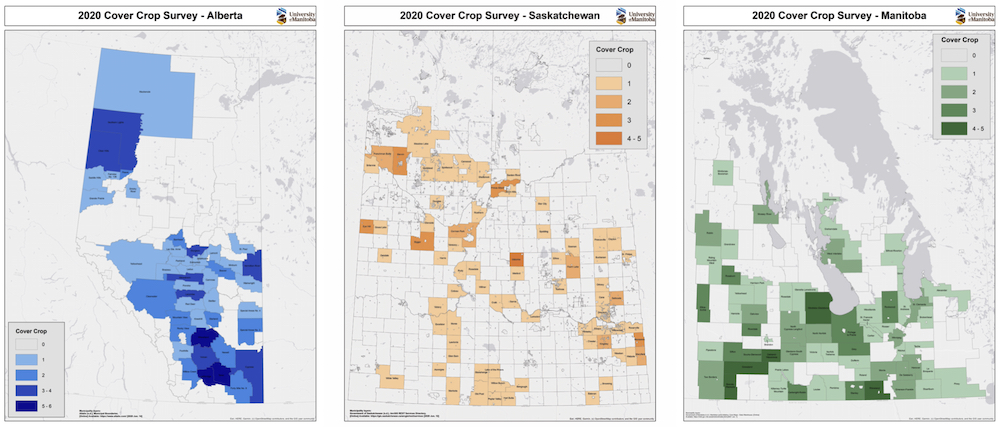

Lawley also thought most of the respondents would be from her home province, but as the maps in Figure 1 show, she was in for another surprise.

“I initially thought, ‘Well, we’ll do this in Manitoba.’ But farmers from Saskatchewan and Alberta were reaching out and saying, ‘We’re doing this too.’ ”

According to Morrison, each of the three Prairie provinces had about a third of the total survey respondents.

“What the maps show me is there are people innovating with this practice and looking at its fit everywhere across the Prairies, and they’re doing it despite the fact cover cropping here is challenging because of environmental and other reasons,” Lawley says. “They are finding ways to overcome the challenges and are doing this successfully.”

Why are farmers growing cover crops?

The following includes the reasons non-grazing farmers said they grew cover crops in 2020 (survey respondents could check more than one option):

- To build soil health, increase soil organic matter — each 72 per cent

- To keep living roots in the soil — 69 per cent

- To feed soil biology — 58 per cent

- For erosion control — 56 per cent

- To increase biodiversity — 53 per cent

- For weed suppression — 50 per cent

- To add nitrogen, improve soil infiltration — each 47 per cent

- For carbon sequestration — 36 per cent

- To combat compaction — 31 per cent

- To scavenge nitrogen, provide food for bees/pollinators — each 25 per cent

- To manage soil problems like salinity, financial gain — each 22 per cent

- For pest or disease control, crop establishment — each 11 per cent

- To improve trafficability — six per cent

What are farmers using for cover crops?

The following includes types of cover crop species grown by non-grazing farmers in 2020 (respondents could check more than one option):

- Clover (any type) — 53 per cent

- Fall rye — 39 per cent

- Buckwheat — 22 per cent

- Oats, peas, radish — each 17 per cent

- Ryegrasses, phacelia — each 14 per cent

- Alfalfa, flax — each 11 per cent

- Spring wheat, barley, chicory, sweet clover — each eight per cent

- Winter wheat, faba bean, hairy vetch, plantain — each six per cent

- Lentils, corn, triticale — each three per cent

Morrison notes many of the cover crop choices are species Prairie farmers are familiar with, and in many instances the respondents used bin-run seed that was handy for cover crop use.

He adds clover topped the list likely because it’s a small seed that can be planted easily and in different ways.

“It can be broadcast, it can be drilled … it’s also quite good for being intercropped, started at some point during the season and then left to grow in the fall. So, there are many opportunities for farmers to establish clover.”

More than half of non-grazing respondents (56 per cent) also chose to use only one species for their cover crop in 2020. Thirty-three per cent chose two or three different species, while 19 per cent opted to use four or five.

“If you do want to just try with a cover crop, there’s nothing wrong with one species,” says Morrison. “The most important cover crop is the one that you can get in that’s cost effective and is providing that cover. You can get that from one species (without) a lot of financial investment.”

How are farmers growing cover crops?

The survey showed non-grazing farmers grew cover crops after a wide variety of cash crops in 2020. The list of cover crops includes the following (respondents could list more than one option):

- Barley — 31 per cent

- Spring wheat — 19 per cent

- Peas — 17 per cent

- Oats — 14 per cent

- Canola, potatoes, vegetables — each 11 per cent

- Lentils, alfalfa — each eight per cent

- Flax, fall rye, forage — each six per cent

- Winter wheat, soybean, sunflower, sugar beet, edible beans — each three per cent

The survey showed many non-grazing farmers grew cover crops on a relatively small percentage of their acres in 2020, including the following data:

- Under 10 per cent of farm area — 25 per cent

- 10 to 19 per cent of farm area — 14 per cent

- 20 to 29 per cent of farm area — 28 per cent

- 30 to 39 per cent of farm area — 11 per cent

- 40 per cent or more of farm area —23 per cent

Morrison says the results indicate farmers generally started small with cover crops, with many choosing to trial cover crops in a limited area before committing to more acres.

This is reflected in the survey, which showed producers tended to increase their cover crop acres over time. A quarter of the non-grazing farmers said 2020 was their first year with cover crops and, of the remainder, 33 per cent indicated their cover crop acres had increased slightly and 11 per cent indicated there was a significant increase.

Only nine per cent said there had been a slight or significant decrease in cover crop acres over time. Fourteen per cent indicated there had been no change, while eight per cent said their cover crop acres depended on the year.

“What we found is farmers generally increase the cover crop acres over time or they maintain them. Very few decrease them,” says Morrison. “I think that falls into the idea that farmers are starting small. They start simple, and if they feel it works, then they choose to increase (acres) over time.”

Intercropping

For Morrison and Lawley, the biggest eye-opener from the survey was how many farmers were establishing cover crops as an intercrop — that is, seeding them between the rows of cash crops, either at planting or later, during the growing season.

The survey results on cover crop establishment as a monocrop or intercrop (respondents could list more than one option) include the following:

- Monocrop grown after cash crop harvest — 53 per cent

- Intercrop planted with a cash crop — 33 per cent

- Intercrop established after cash crop planting — 11 per cent

- Monocrop grown instead of a cash crop — six per cent

Morrison says he found the number of farms practicing intercropping surprising because it generally isn’t something farmers are thinking about.

“This did shock us because we were expecting most farmers to be planting cover crops as a monocrop after harvest. But we found many people were establishing it as an intercrop, really to get around fall moisture issues and to increase biomass,” he says.

“We found as we went west in each province, the proportion of farmers who were starting their cover crop as an intercrop increased. That reflects the realities of the shortening growing season and problems with not enough moisture at the end of the season.”

Morrison says he can understand how intercropping could work well as an establishment method and not interfere with harvest operations.

“Quite often these cover crops are very low down,” he explains. “You could have your wheat but then hugging the ground is some red clover. Your combine won’t come into contact with that.”

In Morrison’s eyes, intercropping is a prime example of how Prairie producers are coming up with innovative ways to integrate fall cover crops into their production systems.

Lawley agrees.

“I think we underestimate the human dimension in all innovation. In farming in general, people are a resource that we often discount when we’re thinking about how we enable adoption,” she says.

“I think this is one of the areas of innovation that we’re seeing as farmers as trying to adapt this practice to the Prairies.

What are farmers spending on cover crops?

The survey also looked at what producers were spending to grow cover crops in 2020. The costs of cover crop seed per acre for non-grazing farmers include the following (respondents could list more than one option):

- No cost — six per cent

- Less than $5 — three per cent

- $5 to $10 — 25 per cent

- $11 to $15 — 25 per cent

- $16 to $20 — 14 per cent

- $21 to $25 — three per cent

- $26 to $30 — 11 per cent

- $31 to $35 — three per cent

- $51 to $55 — three per cent

- $56 to $60 — eight per cent

- More than $70 — six per cent

Morrison notes with half of the non-grazing respondents paying from $5 to $15 per acre on cover crop seed, producers generally weren’t spending a lot of money on the practice.

“A lot of these farmers, they’re keeping their costs pretty low,” he says. “It’s quite often bin-run seed and they’re just growing one type of cover crop, so they’re keeping their costs down.”

How are farmers benefitting from cover crops?

Morrison says it was apparent farmers in the survey generally weren’t growing cover crops to make money like they would for cash crops. But he adds the financial benefits associated with things like enhanced soil health and more soil organic matter were clearly recognized by some, even if they can be hard to quantify.

This recognition was reflected in the survey. Respondents were asked how much influence cover crops had on farm profits. Thirty-one per cent of non-grazing farmers said cover cropping led to a slight to moderate increase in profits, while only nine per cent said there was a slight to moderate decrease.

Of the rest, 11 per cent said there was no change in profits, 11 per cent said it depended on the year, eight per cent said it was unknown and 31 per cent indicated they couldn’t say, since it was their first year growing a cover crop.

The survey also asked producers to check off specific benefits they’d observed from growing cover crops. While 31 per cent of non-grazing farmers indicated they had yet to see benefits, there were many benefits listed by the remainder. These benefits included the following (respondents could check more than one):

- Improved soil health, fewer weeds — each 42 per cent

- Less soil erosion and dust — 36 per cent

- Increased soil organic matter — 31 per cent

- Increased biodiversity — 28 per cent

- Financial gains — 25 per cent

- Increased soil infiltration, fewer pesticide applications — each 19 per cent

- Less nitrogen fertilizer needed, better crop establishment, more earthworms — each 17 per cent

- Fewer pests and diseases, reduced compaction — each 14 per cent

- Improved trafficability — three per cent

Producers were also asked how long (in years) it took to notice the benefits of cover crops. The responses of non-grazing farmers are as follows:

- One year — 31 per cent

- Two years — 14 per cent

- Three years — 11 per cent

- Four years — three per cent

- Five years — eight per cent

“I think the important thing here is the majority of farmers told us they saw benefits … and most of them within the first three years of growing a cover crop,” says Morrison.

“This shocked us because we think of many of these benefits taking a long time to occur,” he adds. “We were surprised how quickly farmers told us they were seeing benefits.”

What challenges do farmers have with cover crops?

The benefits of cover cropping, like any production practice, need to be weighed against potential challenges. That’s especially true in a less-than-ideal environment like Western Canada.

The survey asked respondents to list problems they encountered growing cover crops. Morrison says, in hindsight, they should have asked to identify “challenges” rather than “problems,” since many of the farmers were able to adapt and find ways around them.

The main problems identified by non-grazing farmers in the survey include the following (respondents could check more than one option):

- Late harvest prevented planting — 42 per cent

- Not enough moisture for fall establishment — 31 per cent

- Shortness of growing season — 28 per cent

- Cover crop failure, lack of information — each 22 per cent

- Additional costs — 19 per cent

- Increased labour costs — 17 per cent

Each of the following problems came in at 11 per cent:

- Affected the choice of herbicide(s)

- Less moisture for next cash crop

- Interference with cash crop

- Time taken to plant/manage/terminate cover crop

- Availability of seed

- Unable to terminate at the correct time

The following problems came in at six per cent:

- Didn’t know where to get started

- Added a layer of complexity to farm

- Lack of equipment

- Lack of support from agronomists

- Lack of support from crop insurance

- Control of cover crop residue

- Control of cover crop volunteers

- Carry-over of pests and disease

- Soil too wet to plant/maintain/terminate cover crop

- Opinions of other farmers

It’s notable that 22 per cent of the non-grazing farmers said they hadn’t experienced any problems growing cover crops.

How to get more farmers involved with cover cropping

The 528 survey respondents included 281 farmers who grew cover crops in 2020 and 247 who didn’t. Of these, 129 producers said they wanted to try growing cover crops in the future and 36 said they didn’t.

Morrison says to help determine what could be holding this curious but hesitant group, the farmers considering growing cover crops were asked to list the challenges that prevented cover crop use. The top answers included the following (respondents could check more than one option):

- Shortness of growing season — 43 per cent

- Not knowing where to start — 42 per cent

- Lack of information — 40 per cent

- Late harvest preventing planting — 39 per cent

- Additional costs — 33 per cent

- Lack of equipment — 32 per cent

- Lack of moisture at the end of season — 29 per cent

- Time required to plant/manage/terminate cover crop — 27 per cent

- Interference with cash crop, less moisture for subsequent cash crop — each 19 per cent

- Didn’t want the extra layer of complexity, cover crop failure — each 14 per cent

- Availability of seed — 13 per cent

- Control of cover crop volunteers, ability to terminate cover crop, didn’t want to increase labour — each 12 per cent

- Lack of support from agronomists, affected choice of herbicide(s) — each 11 per cent

- Current system works well — 10 per cent

- Control of cover crop residue — nine per cent

- Lack of support from crop insurance, want soil to remain bare/black — each eight per cent

- Control of cash crop stubble, carry-over of pests and diseases — each seven per cent

- Opinions of other farmers — five per cent

Farmers considering cover cropping were also asked to list measures they thought would enable cover crop use. The top answers include the following (respondents could check more than one option):

- Technical assistance — 63 per cent

- Tax credits for planting cover crops — 57 per cent

- More research specific to the Prairies — 52 per cent

- Payments for storing carbon — 50 per cent

- Greater access to agronomy information — 43 per cent

- Payments from conservation programs — 40 per cent

- Increase in farm profits — 37 per cent

- Other local farmer(s) growing a cover crop — 26 per cent

- Local cover crop farm tours — 24 per cent

- Discounted crop insurance premiums — 22 per cent

- Acceptance of cover crops by crop insurance — 18 per cent

- Creation of local cover crop farm networks — 16 per cent

Morrison maintains the many farmers indicating they lack information and don’t know where to start and the calls for technical assistance, Prairie-specific research and supportive grower networks, shows a clear need for greater agronomic knowledge transfer and support — not only for early adopters but also those who might be on the fence about cover cropping.

“We’ve got cost share programs now, but we really need more agronomists to be trained in this area,” he says. “Essentially, what we have here is a group of farmers who really want to try growing cover crops, but two of the top three challenges limiting them are they just don’t feel they have the information or the support they need.”

Morrison says he believes many farmers “feel quite alone” when it comes to the question of cover crops.

“I think a lot of people aren’t really thinking about this, the lack of information and the need for knowledge transfer.”

Lawley says the survey helped underscore how having specialized cover crop training for both agronomists and farmers and more research examining what works and what doesn’t in the Canadian Prairie context, continue to be in great need.

“I think we’re still struggling on that enabler piece,” she says.

“This represents a particular group of farmers, the early adopters, who went out and started figuring this out before there were supports. But if we’re going to get to wider adoption and move this forward, we’re going to need supports and people trained to work with … that middle part of the adoption curve.”

Another cover crop survey

Another cover crop survey is currently underway in Western Canada, this one by Jodi Holzman.

Holzman is conducting the survey as part of the master of science degree in environment and management she’s working toward at Royal Roads University in Colwood, B.C. She also works full time for Bayer CropScience in Saskatoon, Sask., and has 12 years of experience in the Prairie agriculture industry.

Holzman is asking farmers who have incorporated cover crops into their production systems (with a focus on Saskatchewan producers) to provide information related to cover crop costs, benefits and production practices. Holzman also aims to do some in-depth interviews with farmers practicing cover cropping.

The survey started in March and Holzman has enlisted the help of numerous ag organizations to get it distributed to farmers. To participate in the survey, go to surveymonkey.com/r/covercrop2023.

You can also contact Holzman for more information at [email protected].