Every farmer wants “healthy soil.” But what does that mean, and how do they know if they have it?

“The first question I ask when I’m speaking to farmers is, ‘How many of you have done soil testing?’” says Yamily Zavala, soil health lab manager and soil health and crop management specialist at the Chinook Applied Research Association, Oyen, Alta.

Most farmers in the room raise their hands when she asks this, but when Zavala pushes them further, she finds that most have had an analysis of their soil’s chemical properties. These tests usually analyze micro- and macronutrients, pH, organic matter, electrical conductivity (to indicate salinity) and cation exchange capacity (to indicate the soil’s ability to hold nutrients).

Read Also

AgraCity’s farmer customers still seek compensation

Prairie farmers owed product by AgraCity are now sharing their experiences with the crop input provider as they await some sort of resolution to the company’s woes.

This information is necessary to develop a fertility program, but, Zavala says, it’s far from the whole story.

“Soil is not just chemicals. Soil is not just minerals. Soil is holistic. It’s alive.”

The Chinook Applied Research Association’s Soil Health Lab has been testing soil from across Alberta using three categories of soil properties: chemical, physical and biological.

With more than 4,000 soil samples analyzed between 2018 and 2024, the association’s Alberta Soil Health Benchmark Report includes benchmarks and scoring systems that can provide Alberta growers with comprehensive reports on their soil health in an easy-to-use format.

What is “healthy”?

There isn’t one standard, simple definition of “healthy” soil. Most definitions mention the soil environment and how efficiently the soil cycles nutrients. Almost all definitions use “healthy soil” and “quality soil” interchangeably.

The concept of soil health goes beyond measuring the chemicals and nutrients in the soil and includes how the whole soil ecosystem is functioning.

One common indicator of soil health measures the amount of living microbes in soil. This is soil organic matter, the percentage of soil made up of plant and animal material. Soil organic matter is the basic building block of productive soils, holding the soil together and making soil’s biological functions possible.

We know that a higher percentage of soil organic matter is better. But how much is enough? What other components of soil affect soil organic matter?

What can we measure (besides soil organic matter) to get a good picture of trends, and analyze differences?

Three components of soil health

The theory behind the Alberta Soil Health Benchmark is that healthy soil has three general components. These are the chemical and fertility properties, the physical properties and the soil’s biological properties, such as soil organic matter.

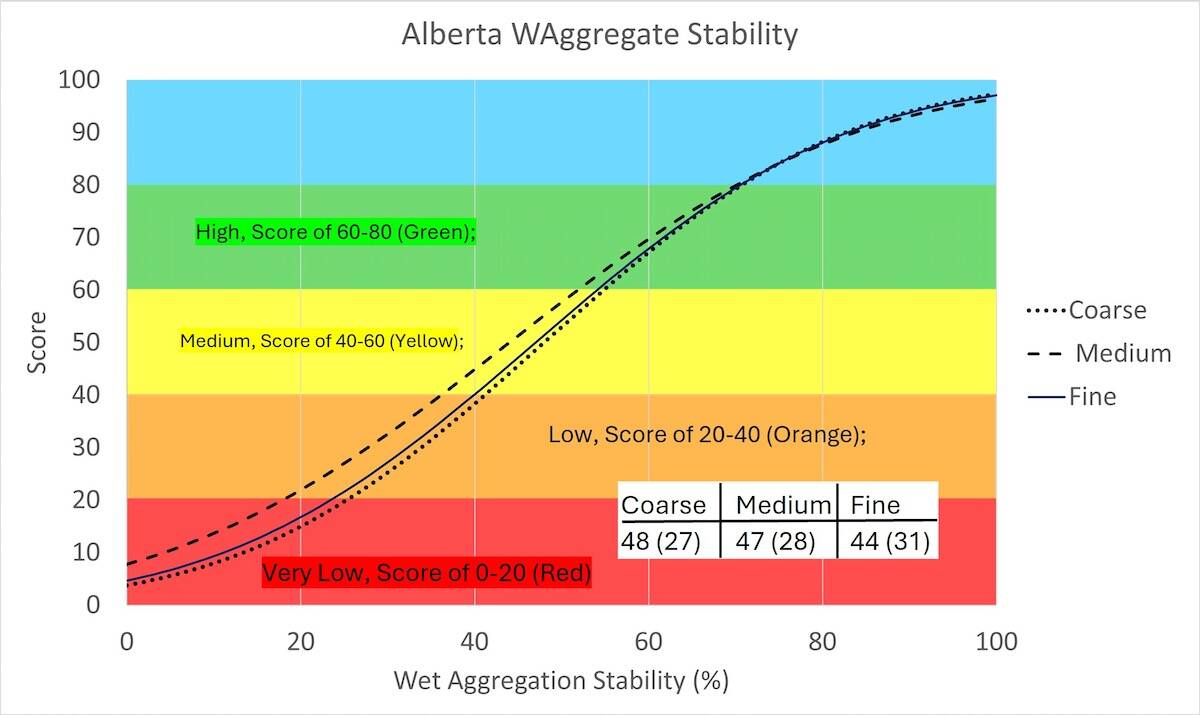

The physical properties describe the inherent character of the soil. Indicators include soil texture, compaction, water infiltration, bulk density (an indicator of soil compaction) and soil wet aggregate stability.

Growers can change some of these physical properties over time through management changes. Other physical characteristics are permanent. Physical properties can constrain soil health and crop yield.

Improving the soil’s physical properties can also improve some of the chemical indicators, the soil organic matter, and other biological indicators. Zavala describes this as “building a really nice house for the biology.”

The third part of the Alberta Soil Health Benchmark evaluation is the biological component.

Zavala sees all three of these components as important and necessary for soil health, but she sees biology as “at the top.” Organic matter in the soil is what allows the soil to function as an ecosystem. The living organisms in the soil are dynamic, changing all the time.

When all three of these components are robust, Zavala says, “that’s what I call the healthy soil.”

Together, all three types of measures provide a snapshot of the health of the soil. With repeated, consistent tests, changes in these measurements will indicate where farm management is improving or depleting soil health.

Measuring biological health

Soil organic matter is a key indicator for measuring soil’s biological health. Soil organic matter is measured by drying the soil, weighing it and then heating it to a temperature that will burn off the organic matter. The remaining soil is re-weighed; the difference in weight is the organic matter. The measure is provided as a percentage of the total soil mass.

The soil organic matter includes many living organisms. Some of the smallest are bacteria and fungi. These produce their own secondary metabolites and digestive enzymes, they absorb pieces of plant residue, and they release nutrients that plants can use.

Among farmers and agronomists, nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as rhizobium are probably the most popular creatures in this category. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia, a form of nitrogen that can be converted into plant-available nitrogen.

Protozoans in the soil are generally larger than bacteria and fungi and can move themselves through the thin film of water in the soil. They’re single-celled, but typically bigger than bacteria and fungi. They often consume bacteria, and sometimes fungi. This group of microbes (living organisms too small to see without a microscope) includes flagellates, amoeba and ciliates.

Nematodes are the largest microbes in our soil. They have multiple cells and can consume bacteria, fungi and protozoa. Most nematodes are beneficial to soil health, but some are agricultural pests that take nutrients from plants, such as cereal cyst nematodes. A diverse group of nematodes in the soil is thought to indicate a healthier soil.

Measuring soil organic matter measures the amount of life in the soil. Other tests examine what that life is actually doing under there.

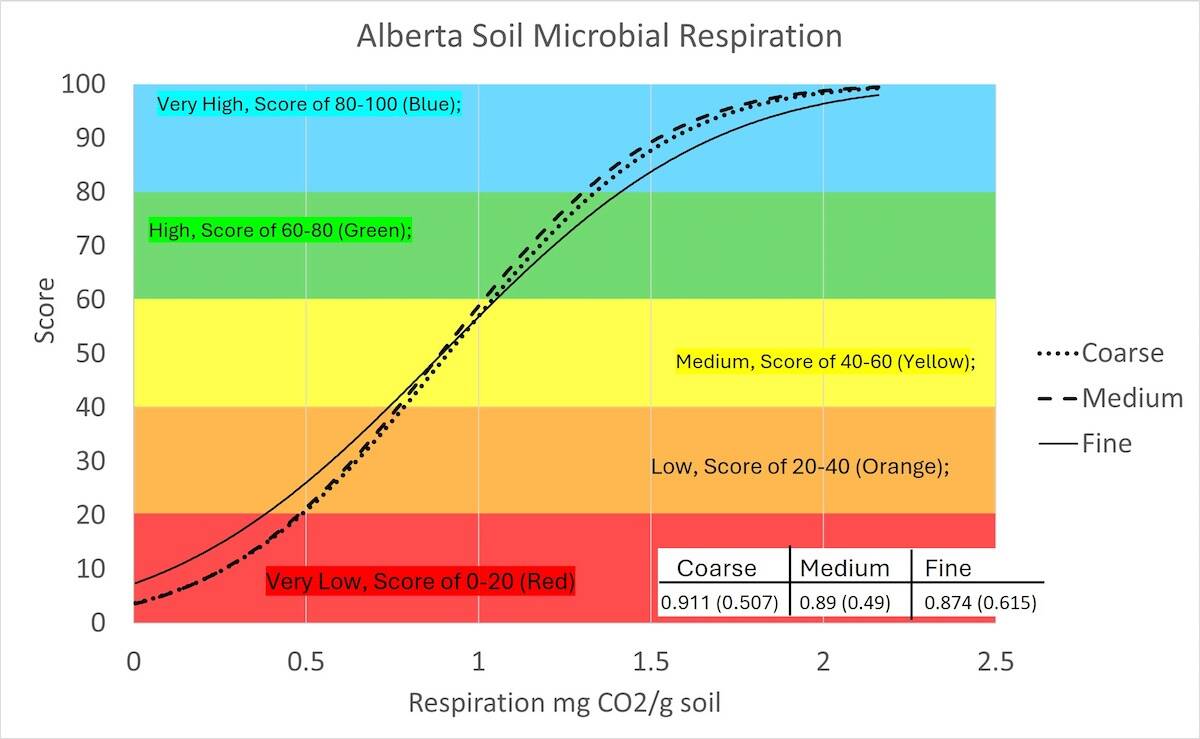

Soil respiration is a measurement that captures a snapshot of the organisms’ metabolic activity. Soil respiration is measured by air-drying soil, rewetting it, putting it in an airtight container, and then measuring the amount of CO2 produced by the rewetted soil. Results are provided as mg of CO2 per gram of dry-weight soil.

When the microbes are more active, they release more CO2. Some ways growers can increase soil respiration include adding more organic material to the soil, adding manure or cover crops, or diversifying crops. Too much tillage can lower the soil respiration rate.

Active carbon measures the share of soil organic matter that can serve as an immediate food source for living organisms — decomposed matter that plants can consume quickly. A high active carbon test result means the microbes have enough food and are producing matter useful to plants.

Active carbon is measured by adding purple potassium permanganate to the soil. Active carbon causes the purple solution to lose its colour. The amount of active carbon in the soil correlates to the amount of colour change. Active carbon is a useful early indicator of changes to soil health. This test will show the effects of a management change sooner than changes to soil organic matter measurements.