The drought of 2021 and the poor crops as a result have left us wondering what residual nitrate-nitrogen might be present in the soil to feed the 2022 crops.

Nitrate in the environment

The first thing we must realize is nitrate in the environment is, for the most part, a function of human activity in some form or another. When our native Prairie grasses were dominant, the nitrate ion was a rare beast. If a wayward molecule of nitrate managed to be released from the soil organic matter, there was a hungry grass root waiting to suck it up.

Read Also

AgraCity’s farmer customers still seek compensation

Prairie farmers owed product by AgraCity are now sharing their experiences with the crop input provider as they await some sort of resolution to the company’s woes.

When our grandfathers came with their big steam engines and plows to turn over the rich Prairie soil for farming, nitrate was released in spades and made available to the wheat crops they planted.

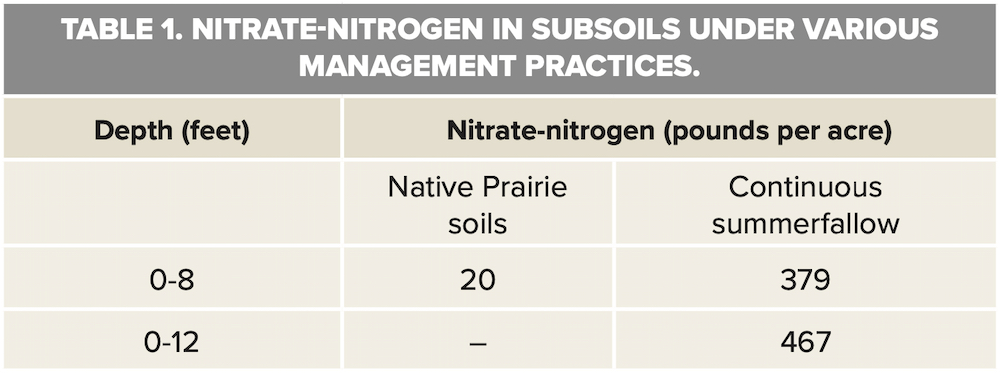

The first research program I conducted at the University of Saskatchewan was to investigate nitrate-nitrogen in subsoils under various management practices. One area investigated was Sutherland clay soils just northeast of Saskatoon.

Sites included native prairie on the U of S Kernen Crop Research Farm and long-term continuous summerfallow areas between tree rows at the Federal Saskatoon Forestry Farm. Our objective was to get to a depth of 20 feet but with the equipment available eight feet was all we could manage on the dry native prairie and 12 feet under the moist continuous summerfallow.

The results of the research project can be found in Table 1 below.

Nitrate is a fickle beast. It carries a negative charge, so it does not cling to the negative charge of soil clays and organic matter. It does not matter if the nitrate comes from native soil organic matter, breaking up an alfalfa field or from overapplication of nitrogen fertilizer.

Enter public soil test labs in the 1960s

Soil nitrate-nitrogen has been the go-to soil test to guide nitrogen fertilizer recommendations for many decades. It all started in Manitoba in the 1960s. Bob Soper, a professor of soil science at the University of Manitoba, did field experiments to show soil nitrate to a depth of four feet could be used to recommend the fertilizer nitrogen needed for a good crop.

Further work by the newly established Manitoba Soil Testing Lab showed soil nitrate to a depth of two feet gave the best correlation and that depth has been the standard to this day.

Keener PAg and CCA types can check out Soper and Huang, 1963, Canadian Journal of Soil Science, Volume 42, pages 350-358, and Soper, 1971, Agronomy Journal, Volume 63, pages 564-568.

The standard depths of soil samples for the Saskatchewan Soil Testing Lab, which was established in 1966, were zero to six inches, six to 12 inches and 12 to 24 inches. There were many years with those standard depths. Nitrate was measured at all depths, but phosphorus and potassium were only analyzed in the zero- to six-inch sample. In later years, the depths became zero to six inches and six to 24 inches, and that remains the gold standard.

The two-foot nitrate sample from many thousands of stubble and summerfallow fields in Saskatchewan over many years was very useful information. The difference between the major soil zones and between summerfallow and stubble set the thinking that led to many advances. It was nitrogen more than moisture that was limiting stubble-seeded crop yield and nitrogen fertilizer quickly fixed that problem. Add zero till to the mix and, voilà — our present farming practice that builds rather than degrades soils.

Residual nitrogen fertilizer in dry years

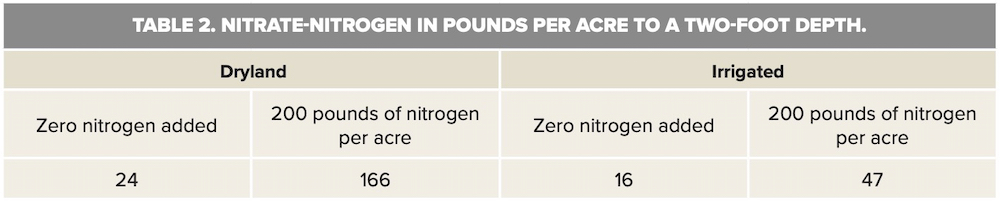

When the Saskatchewan Soil Testing Lab was in full swing, we were busy with field experiments to define fertilizer practices for the newly developed South Saskatchewan River Irrigation District at Outlook. Just pouring on water and carrying on with dryland fertilizer practices did not cut it.

We carried out dozens of field experiments to define the interactions between water and nutrients — particularly nitrogen. One large test in the mid-1970s had barley, wheat and canola, dryland (six inches of rain) and irrigated (rain plus 12 inches) and nitrogen rates from zero to 200 pounds per acre. A very detailed fall soil sampling program after the crops were harvested included samples from each of the four replicates of all the combinations of crop, water and nitrogen. I have boiled that all down to four numbers in Table 2 below.

That data clearly shows in a dry year a high rate of nitrogen fertilizer will leave a significant residual for the next crop.

The nitrogen was granular ammonium nitrate (34-0-0) surface broadcast at the time of seeding. Ammonium nitrate was a very good source of nitrogen fertilizer but because of clowns that used it to blow up a building, we no longer have that option.

Fast-forward to 2021 and looking to 2022

There has been much discussion after the miserable 2021 crop about the nitrogen that might be left behind to serve for the 2022 crop. Many farmers and the agronomists that serve them have conducted extensive soil testing, so they have that information to guide fertilizer practice for the 2022 crop. With nitrogen fertilizer prices at a buck a pound or more, that residual nitrogen has considerable value.

In the days of the Saskatchewan Soil Testing Lab, soil test summaries were published based on soil zone, soil type and administrative zones. When a year like 1988 came along the story was clear – nitrogen was left over for the next year. In those days, the nitrogen rates being used were much lower than today, so the leftovers were not as high, but they were there.

I have been a member of the Soil Science Society of America for decades and pay an additional annual fee to ensure access to all of the journals, magazines, etc. A very useful Crops and Soils magazine has always been a welcome addition to the mailbox with timely pieces of useful data. In today’s world, it hits my email inbox, and I recently received the January-February 2022 edition.

It was a great delight to see a timely piece entitled, “Drought Demonstrates Value of Fall Soil Nitrate-Nitrogen Testing in the Northern Great Plains,” by John Heard of Manitoba Agriculture and John Breker of Agvise Laboratories of Northwood, North Dakota.

The graph directly to the left is Figure 2 from that piece in the January-February 2022 issue of Crops and Soils.

That data resonated with me as it shows a long-term record back to the serious dry years of the late 1980s. Take note that the data is not average values — it is the median value. And the median value of 67 for 2021 means half of the data points were greater than 67 and half were less.

The median is the best statistic to use for soil test nutrient values because it does not follow a normal distribution. A large soil test dataset usually has a few very high values that skew the average to a high value.

There is a Figure 3 in that Crops and Soils paper that shows soil tests by postal code for Manitoba. The highest soil nitrate-nitrogen median value was 102 pounds per acre for zero to 24 inches, and that was the Interlake area of Manitoba. In my Soil Moisture Map for November 1, 2021, (see Grainews, January 18, 2022) we mapped the Manitoba Interlake as red = very dry. That fits with the very high residual soil nitrate-nitrogen.

If readers want to access more soil test summary information for many nutrients, they can check out agvise.com/resources/soil-test-summaries. Thanks to Agvise Laboratories for providing that service. Please note, I have no financial interest in that lab. Regular readers will remember that John Lee of Agvise (recently retired) carried out that 19-year soil salinity/tile drainage project, which answered a question I wondered about for many years.

So, there you have it. Many of you that have grown huge yields with high nitrogen fertilizer in wet years have a good chance of having soil residual nitrogen for 2022. If you have no soil test data, a simple calculation is to subtract the nitrogen you hauled off to the elevator from the nitrogen you applied. For wheat, you likely know the protein content. Divide the percentage of protein by 5.71 to get the percentage of nitrogen in the grain and use the yield to get the amount per acre.