As we gear up to fill the sprayer and begin killing weeds maybe we should take another look at what is in the other 999 gallons in the sprayer. It is well known that the water should be clean with no silt or debris present, but this piece deals with the dissolved “goodies” you cannot see.

One of the last research projects I was involved with at the University of Saskatchewan dealt with the effects of some of our bad waters on weed kill. I am not aware of any current work on that topic.

Read Also

AgraCity’s farmer customers still seek compensation

Prairie farmers owed product by AgraCity are now sharing their experiences with the crop input provider as they await some sort of resolution to the company’s woes.

Glyphosate and hard water

In Saskatchewan, hard water is common, particularly when it comes from a well. Saskatchewan folks often refer to water so hard that the spoon will stand up straight in a cup of coffee.

Hard water is also known for its ability to curdle soap and make it ineffective for washing. In our many years on the road staying at small town motels, we could judge the water hardness in the shower.

What makes water hard is the amount of calcium and magnesium dissolved in that water. Hardness is expressed as the parts per million (ppm) of calcium and magnesium expressed as the calcium carbonate equivalent. Water hardness is sometimes expressed in grains per gallon — an old unit still in use by water well drillers and others who use Hach kits to measure hardness in the field.

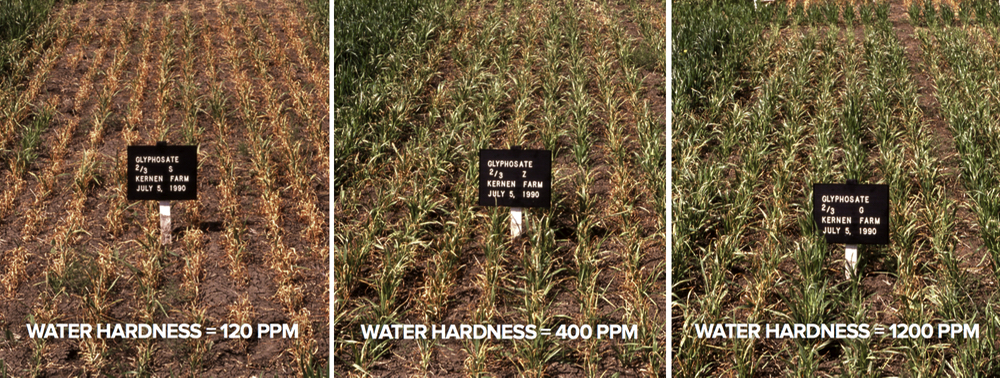

The photos show the story with glyphosate applied in the field at 2/3 of label rate. Water hardness can take the edge off weed control with glyphosate herbicides big-time. In Photo 1, Saskatoon tap water, that is water from the South Saskatchewan River, was tank-mixed. In Photo 2 the water came from a shallow (25 feet) glacial aquifer near Zelma, 40 miles southeast of Saskatoon. The water in Photo 3 came from a deeper (130 feet) glacial aquifer on the University of Saskatchewan Goodale farm near Saskatoon. The photos speak for themselves.

We often think of surface water as being less mineralized because it mainly comes from run off from snowmelt or rain. But, surface waters can be almost anything. Just because the water appears to be clear is no assurance that it is not laced with minerals.

If there is any evidence that glyphosate herbicides are not performing to expectations, the first order of business should be a water analysis. A water analysis for total minerals can be done in the field with a simple electrical conductivity (EC) meter. Water hardness test can also be done in the field with an inexpensive Hach kit.

It has amazed me that almost no agronomy consultants seem to be interested in doing such a simple test that can have such great economic implications. To be sure, field tests must be kept honest by measuring known water and by laboratory tests for some samples but the payback could be huge with an instant answer.

I recall a phone call from a farmer about 100 miles northwest of Saskatoon who was having trouble with Roundup herbicide. The water he used came from a slough and was very clean with nothing growing in the slough or around the edge. He sent us a sample for analysis and the hardness was off the scale. Beware that crystal clear water. It can hide any amount of dissolved minerals.

Well water

For the most part, water from wells in Alberta is soft. The thickness of glacial deposits is much less over most of Alberta. Hence, most Alberta wells are completed in bedrock (pre-glacial] aquifers which contain soft water.

I have just downloaded the PDF of the famous Alberta “Blue Book,” Crop Protection 2019. The section on water used for spraying mentions glyphosate concerns with mineralized water but there is no specific mention of hard water. I think that is appropriate because very hard water is rare in most Alberta wells.

When we move into Saskatchewan, and particularly the central regions of Saskatchewan, hard water is very common.

Water Volume

For glyphosate herbicides, a lower water volume (five gallons per acre) is much less of a problem with hard water than higher water volumes (10 gal./acre). In the 1990s Ken Kirkland of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Scott, Sask., did work with one, five and 10 gallons of water. At one gallon of water the kill was great. That was done with small plot equipment and very low rates were not considered feasible with field equipment at that time. I do not know if modern sprayers can deliver lower water volumes and still get coverage. Maybe some reader can enlighten us.

High Bicarbonate (HCO3-) WATER

Water high in the bicarbonate ion can have an affect on the herbicides in the “dim” group: tralkoxydim, sethoxydim and clethodim. The original trade names were Achieve, Poast and Select respectively. I know of no recent work with this group of chemicals and high bicarbonate waters so changes in formulation may have changed the picture. In the work we did years ago very high bicarbonate (1,000 ppm+) water could seriously reduce the efficacy of that group.

The good old standby 2,4-D amine is also affected by high bicarbonate waters. I recall a farm meeting at Estevan many years ago. In those days we took lab equipment and a technician with us to the meetings. Farmers were encouraged to bring their spray water for analysis on the spot. While we were preaching the gospel, the tech was getting the answers ready. When we got to the subject of 2,4-D and well water one farmer jumped right up and said, “Now I know why 2,4-D amine never worked in the fall. By fall my sloughs were dry and I used well water.” The highest bicarbonate we ever encountered was at Estevan and it was 1,400 ppm bicarbonate.

Note: 2,4-D Ester is not affected by water chemistry. I remember joking that you could mix it with sea water, but that is probably a stretch!

High bicarbonate waters are mostly restricted to bedrock (pre-glacial) aquifers that are often quite deep. Southeast Saskatchewan is the main area but some high bicarbonate well waters can be encountered in southwest and west central Saskatchewan. Milk River aquifers of southern Alberta can also be high in bicarbonate.

Henry’s Handbook has a chapter (10) that shows EC, Hardness and HCO3- for a cross section of waters of the Prairie Provinces.

As you tune up the sprayer to get ready for weed control, be sure you know what is in the other 999 gallons you put in the tank.