Regular readers may recall my Jan. 21, 2020 column that showed monthly temperature data for Swift Current, Sask., from 1886 to 2018. That was followed by my March 24, 2020 column that included sites from North Dakota, which provided the same conclusions.

Weather is the day-to-day, month-to-month and year-to-year conditions that we experience. Climate is the 30-year average of weather data. To study climate change we must look at how the 30-year average is changing.

Read Also

AgraCity’s farmer customers still seek compensation

Prairie farmers owed product by AgraCity are now sharing their experiences with the crop input provider as they await some sort of resolution to the company’s woes.

Starting with 1886 as the first weather data, the first climate data available is 1915. The 1916 climate data is an average of 1887-1916 and so on with a moving average.

Some folks interested in crop production talk about resilience needed to adapt to the global warming that will fry us out. However, we must look at the months that actually affect crops.

Since the work in 2020, I have assembled data from six stations in Saskatchewan, three in Alberta, two in Manitoba and a few in the northern United States. The observations and conclusions are the same at all stations:

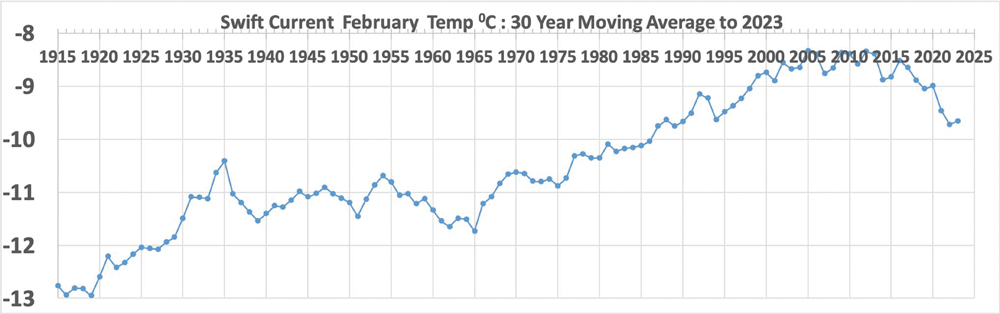

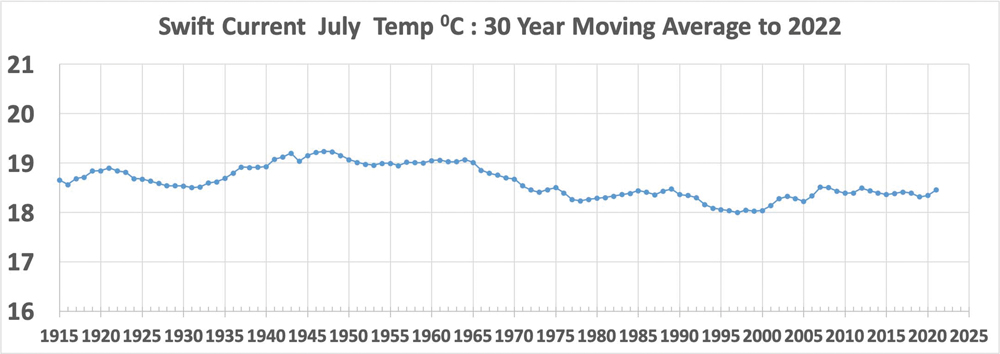

- January, February and March have a range of 5+ C and that data drives the annual average. The range in July is only 1 C.

- January, February and March warmed by about 3-5 C from the 1970s to 2000 and levelled off after that.

- July cooled almost 1 C from 1965 to 2000.

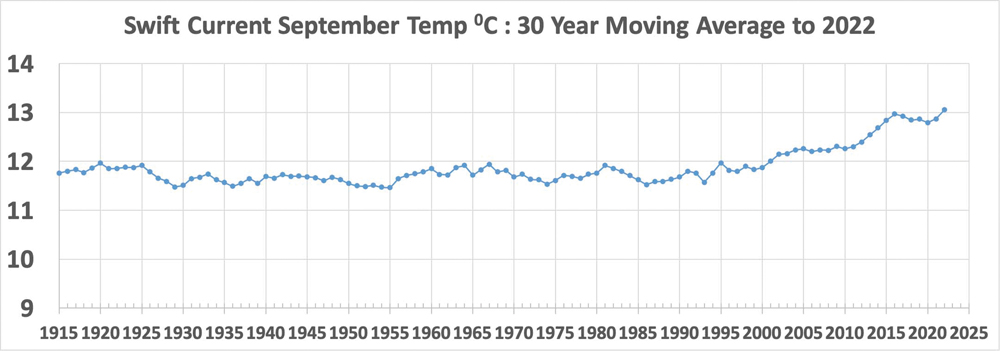

- From 1990 to 2018, September warmed more than 1 C, which was observed at all sites examined so far.

We do not grow crops in January, February and March. July is cooler, so only the warming in September has any effect on crop growth. Most years, September warming will have little effect on actual growth, but in the years with a wet spring and mid-June seeding, it can make a huge difference to not have a September frost.

Now the update

In recent weeks, I have updated the Swift Current temperature data to 2023 for January, February and March, and to 2022 for the remainder of the months. Here is what I found.

February temperatures peaked in 2000, were flat for a few years and have dropped sharply since 2015. March and April have also cooled in the same period.

July temperatures have cooled about 1 C from 1965 to 2000 but have risen about 0.5 C since then.

September has warmed about 1 C since 2000.

Conclusions

Based on this data, I conclude the recent episode of global warming in our area ended about the turn of the century.

We have much more to fear from cold than warm. In our neck of the woods, the warming has been mostly in months where our crops are in the bin or off to market. On an anecdotal and weather basis, this past winter has reminded me a lot of the winters when I was growing up on Brunswick Farm at Milden, Sask., in the 1940s and 1950s.

The winter of 1955-56 was a beast and did not break up until late April. I spent more time billeted in town than on the farm. Friday after school, I would walk the railroad track for three miles to get to the farm to help Mum and Dad get feed into the barn loft to feed the cows for the next week. Monday morning, I walked the railroad back to town. All roads and highways were blocked with snow.

So, there you have it — the facts as I have assembled them. These are facts, not guesses based on complicated mathematical models that use annual weather data, mostly starting in 1950 and based on annual data and not 30-year averages.

Remember, climate is defined as the 30-year average.