In the fall, when the spring calves are weaned and removed from the cow herd, most producers walk through their herd on pasture or at home and think about which cows they should cull. Once candidates are picked, another decision is made as to whether to sell them immediately or feed them for the next few months to put on some saleable weight. Whatever the final decision, it’s based on pure economics.

There might be many reasons that beef cows are culled, but on top of most cull lists is open cows. After all, it’s the lifeblood of all generating cow-calf revenue and profits — all cows should be pregnant by 80-90 days after calving so that they drop a calf at the same time every year. Straggler cows that often breed/calve outside a tight breeding/calving season are also potential cull candidates. They tend to upset the perennial generation of weaned calves of uniform size and heavier weights that translate into more income for the operation.

I asked a long-time producer who operates a 400 Angus/Simmental cow herd if there were any exceptions to the rule of culling an open cow. He said that even if it were the best cow of the herd and was guaranteed to rebreed next season, she is clearly a depreciated item, because:

Read Also

Get ready for an eventual transition on cattle traceability

When new federal cattle traceability rules do ultimately take effect, reporting requirements will vary for producers, transporters, feedlots and markets — but most of the onus will be on producers.

1. She did not give birth to a calf that generates one cent of saleable revenue;

2. She will then incur at least a $3/per day bill for overwinter feed and housing costs (200 days) or a $600 liability; and

3. Still retains a current attractive cull value, which allows good replacement bred heifers of less market value to enter the herd.

Even though being open might not be the fault of the cow in the first place, this producer stood by his culling guidelines. For example, since much of this producer’s cow herd breeding season falls during the hottest days of summer, many apparent infertile cows (as well as breeding bulls) might actually suffer from heat stress-related infertility. My friend says it’s unfortunate, but these cows must be culled.

Age takes a toll

Aside from open cows, culling old cows out of the herd is another good reason. That’s because healthy and fertile beef cows have a viable reproductive life of about seven to eight years. Overall fertility slips by 10 years, and steeply declines after 12. Furthermore, as young cows become old cows, their bodies slowly break down; teeth become broken and worn down, and periodic digestive upsets take their toll on nutrient uptake. Teats and udders collapse for good milk production, plus uterine disorders increase and repeat themselves. General lameness becomes more frequent.

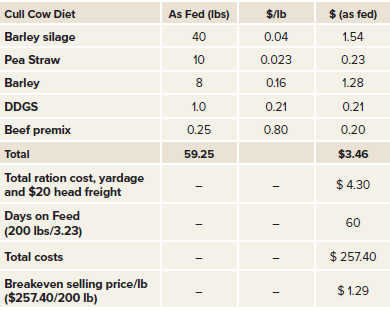

Whether to sell off these open and old beef cows immediately or put them in a drylot to gain a couple of hundred pounds is based on pure economics as illustrated in the attached spreadsheet.

The parameters are based upon: (1) feed mature beef cows (1,300 lbs.) in to gain 200 lbs. in 60 days, (2) feed them a typical beef cull cow diet, (3) cull feed efficiency = 10 lbs. dm diet/lb. gain or ADG = 3.23 lb/head/d (4) yardage = $0.50/head/day and (5) breakeven cull cow selling price is based on live bodyweight.

As a matter of personal management, the above cow-calf operator sold a truckload of old cull cows during late summer and received $1.28 – $1.33/lb. for his 1,400-lb. cull cows. I expect the value of the cull market in November/December might drop since a significant volume of cull cows traditionally enters the market. The spreadsheet might dictate that the best time to sell cull cows is still within a couple of weeks of the upcoming weaning season.

Despite any marketing opportunities for cull cows, there is usually about 15 to 20 per cent of the cows in most cow herds that should be culled. Therefore, producers should always make good decisions based on their pure economic status; eliminate or cull cows that don’t make a profit, and keep the majority of cows that do.