While there will always be a role for breeding bulls on the farm, a recent Saskatchewan study says producers may want to look at artificial insemination of commercial beef cows, which could put more calves and more pounds of beef on the ground.

In the report published late last year by the Western Beef Development Centre (WBDC) at the Tremuende Research Ranch near Lanigan, lead researcher Bart Lardner compared two 40-head herds of similar Black Angus cows in AI and natural breeding programs. The AI group netted $11,000 more over the natural service group with more calves weaned, more pounds of beef produced and savings of about $275 per head.

Read Also

Get ready for an eventual transition on cattle traceability

When new federal cattle traceability rules do ultimately take effect, reporting requirements will vary for producers, transporters, feedlots and markets — but most of the onus will be on producers.

Lardner says there are a couple of qualifiers — it was only one year, and it may not be suitable for every farm, “but considering what it costs to buy and keep breeding bulls, AI service may be something for producers to consider.”

He says the value of AI isn’t just a one-year event either. It can afford producers an opportunity to introduce some high value genetics or some specific traits into replacement cattle they may not be able to afford if looking at higher value bulls.

The five- to six-year-old Angus cows were bred in the spring of 2013 with calves weaned October 2014. Lardner used a fixed-time artificial insemination (FTAI) program with the one group. They were administered a progesterone program to bring them into heat at a fixed time. A certified commercial AI service technician handled the actual insemination as cows began to cycle within about 48 hours of the synchronized heat-inducing treatment. Ten days after the AI service, cleanup bulls were placed with the cows for 47 days.

- Read more: Fine-tuning replacement heifer savings

The other natural service group of 40 Angus cows was exposed to breeding bulls over a 63-day breeding season. The bulls were tested for fertility and soundness and distributed with cows at a ration of 25:1 (cows to bulls).

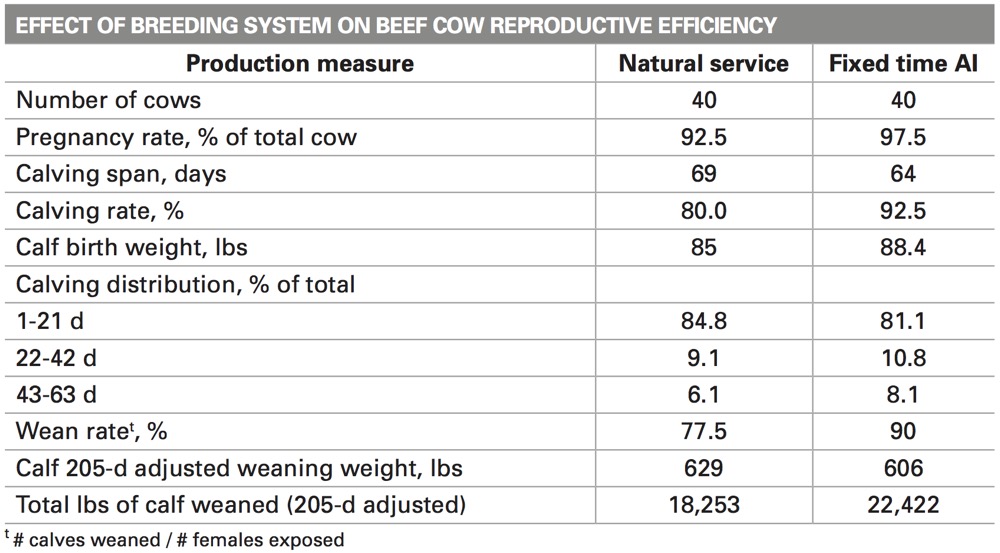

Both groups were preg tested 90 days after the FTAI program. Here are some numbers below.

More calves on the ground

Assuming all things being equal, the AI group had a five per cent higher pregnancy rate than the natural service group. The AI group had a 12.5 per cent higher calving rate — more calves on the ground with slightly higher birth weights. The AI calves had a slightly lower weaning weights — 606 pounds versus 629 pounds — but again a 12.5 per cent higher weaning rate (more calves weaned per female exposed).

At the end of the day, the AI calves had a total weaning weight of 22,422 pounds compared to the natural service calves that weighed in at 18,253 pounds. Lardner used a market value of $2.90 per pound in 2014 to calculate values.

So what does it all mean? Lardner says he doesn’t think herd size should matter. An AI program could have an economic benefit whether you’re running 50 head or 500 head. The decision depends on the individual farm, labour available and degree of management a producer wants to invest in an AI breeding program.

A look at the costs

Keeping five or 10 bulls or more on the farm isn’t cheap. In this study, WBDC economist Kathy Larson figured it costs about $2,124 annually to keep a bull. She based that on a bull with an initial purchase price of $4,000 (minus salvage value) that provides three years of service.

Annual direct feed and medical costs came to $622 per bull, there was a yardage cost of $216 per head, bull depreciation was pegged at $685 per year, and risk of loss was given a value of $600 per head. That totals $2,124 which works out to about $85 per cow (assuming 25 were serviced).

But AI isn’t free either. For this study, Larson calculated it cost about $5,165 to AI the 40 head of cows. That included about $2,232 for the synchronizing treatment and semen and another $715 for the AI technician. The cleanup bull was valued at about $1,700 and he earned his keep. In this study among the FTAI group there was a 50 per cent conception rate with AI service and 20 natural service conceptions. Larson added another $520 in ranch labour and handling costs. So the AI program cost $5,165 for 40 head or about $130 per cow.

The benefits of the FTAI program came in two places. The AI program had higher costs than natural service, but then it generated $12,090 in increased revenue. Along with that the project also calculated about $5,000 in reduced costs with the AI group due to fewer bulls required, and fewer replacement heifer calves needed.

In the end, the FTAI program had about $17,014 in gross higher profits. Taking away about $5,900 in extra costs, it left a net profit of $11,110.

“Planning is a crucial part of developing this type of AI program,” says Lardner. “You need cattle to have proper nutrition and be in good condition leading up to the date of AI service. You’ll also need some proper facilities for processing cattle. Increased labour is also a factor. So a producer has to look at what they are trying to achieve and be prepared to supply the extra management to make the program work.”