Can we feed nine billion people in the next 50 years? This was the question posed by Dr. Lutz Goedde at FarmTech in Edmonton in January. Some of the statistics Geodde presented to explain his answer were interesting to say the least.

In the next 50 years, the world is going to have to cumulatively produce as much grain (volume-wise) as we have in the past 10,000 years put together.

The amount of arable farmland has increased dramatically over the past 15 years with the majority of the new land being in South America through deforestation. The level of deforestation has dropped dramatically the past couple of years due to cheap grain values brought on by export restrictions and tariffs that governments have put in place in those regions. The past two years of bumper world production have sent grain prices to five-year lows, which will not encourage the cleaning of any new land. So how will we produce enough grain to feed nine billion people in the next 50 years if we don’t have more land?

Read Also

Farm equipment market unlikely to pick up

North America’s farm machinery sales have been slow and uncertain thanks to tariffs and trade disruption. There’s not a lot of hope for change in 2026.

The first place to look at is waste in our current food chain worldwide. Across the globe, we waste approximately 30 per cent of our available food stuffs every year.

In developed nations, we waste the food at the consumptive end of the food chain —throwing away spoiled food, ordering too much food at a restaurant and buying bulk amounts that spoil before we can consume them.

In developing nations the waste happens much earlier in the food chain, at the production and food storage points in the process. Countries in Eurasia and African struggle with grain harvest and storage due to inefficient harvest practices, poor storage and their hot, humid climate.

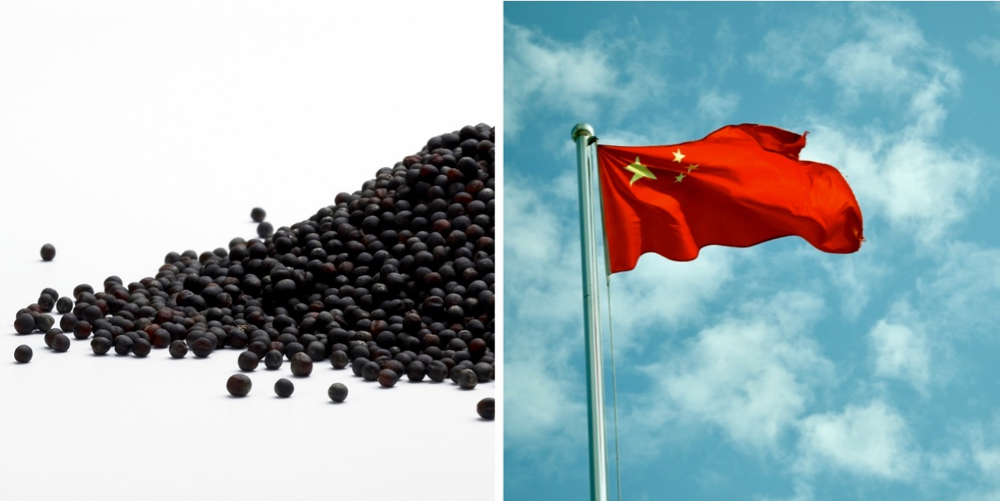

China’s involvement

After absorbing Goeddes’ comments and having read other relevant articles these are my thoughts on what this could mean for world grain markets.

China has for many years been trying to become self-sufficient in grain production but they have been losing that battle — population growth is outpacing grain production growth. To increase grain production the Chinese government adopted policies such as paying highly subsidized prices to farmers to encourage more production to meet self-sufficiency targets.

The stocks the government buys are stored in massive facilities and later sold to domestic mills and processors or strategically sold into export markets. Some grain is held to feed the people or to buffer them from years of poor production. Millions of tonnes of grain are stored for long periods of time, which only increases the risk of loss from spoilage.

Sinograin, the state stockpiler, purchased a record 125 million tonnes of domestic grain in 2014. With the recent drop in world prices Chinese mills and processors have been able to import grains cheaper than they could buy them from the government. Stockpiles are now at record levels and facilities are full —they have no room to buy or store new crop grains.

I believe these factors have helped lead to this recent announcement out of China. On February 3, Reuters reported that China would be giving the market a bigger role in setting prices and moving away from a “controversial state stockpiling policy that has led to bulging grain inventories and a surge of cheap imports.”

The Chinese appear headed towards changing their grain security strategy from one of storing and hoarding massive inventories to a more strategic plan of managing production on lands they control.

Apparently the Chinese have figured out that it will be cheaper to buy grain from the markets than to pay subsidized prices, store massive amounts and lose a big portion to spoilage and theft every year. Just the elimination of waste in storage could equate to hundreds of millions of dollars in savings.

The Chinese do not want to be at the mercy of the world grain markets in a year when stocks are tight and prices soar, which as I see it is the main reason why over the past several years they have been investing heavily in agriculture lands around the world. They want surety of supply at stable prices and there is no better way to get that than to grow more of their own grain to avoid having to buy in volatile markets.

How much grain the Chinese have in storage has always been a mystery to the outside world and no doubt they will always keep some in storage as protection against the unknown.

This brings me to ask some questions: How long will it take them to reduce those inventories? Could this keep world prices under pressure? For how long? Will China’s becoming a more hand-to-mouth buyer add volatility to world markets? Do any of you have any answers The best I can come up with is “it depends.” To be continued.