One thing machinery brands have emphasized for decades when introducing new machines is the incremental improvements they’ve made in ergonomics in the cab. Controls continually get easier to manipulate and feel more natural to use, and cabs get more comfortable.

Having attended more than a few machine introductions, I’ve heard brand marketing staff describe in detail how control arrangements and cab layouts were the focus of a lot of research efforts, which usually included inviting focus groups to try out potential designs. Making control layouts better was the goal because operator comfort has become a major selling point for brands.

Now, as machines continue to integrate automation into so many systems, there is a need to understand a new kind of operator ergonomics. This time it’s about how to improve communication with all of those automated features built into today’s equipment.

Read Also

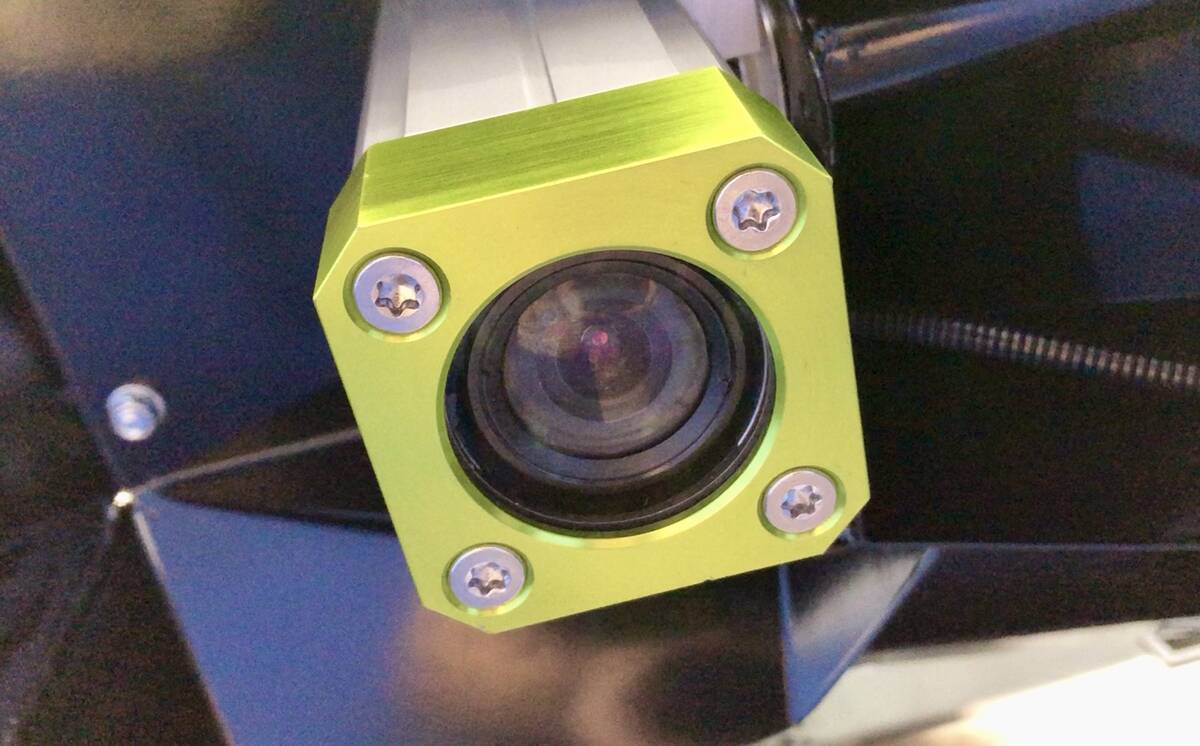

Yield EyeQ camera system measures harvest loss at header

Harvest equipment manufacturer Geringhoff won a silver Innovation Award at Agritechnica for its Yield EyeQ camera system, meant to help farmers measure grain loss at harvest.

Not only do operators need to easily input instructions, but they need to get good feedback from the machine allowing them to understand what’s happening under the sheet metal or with the implement behind the tractor.

And that need also goes one step further. As machines move steadily toward full autonomy, how can supervisors, who aren’t in the cab of that self-driving equipment, best input commands and receive feedback? It’s that overall area of research that Danny Mann, a professor of biosystems at the University of Manitoba (U of M) in Winnipeg, Man., has been focusing.

“Anytime we, as a human operator, are interacting with any kind of a machine, I need to be able to give instructions to that machine — that’s the input. I also need to get information back from the machine, so I know what’s happening,” he said during a seminar at the U of M in February.

“We need to understand how information is going to be shared in that (increasingly automated) environment. That really became the focus of my research program.”

A key part of his ongoing research involves test subjects sitting in a simulator as research staff monitor what systems allow for the most user-friendly and efficient methods of communicating with the machine.

At first Mann relied solely on recruiting farmers to participate in various testing and evaluations, but that proved to be inefficient and inconsistent.

“That led to steps to develop a lab that would allow us to study this,” he explained. “Some of the research tools we’ve used over the years include a driving simulator (and) eye-tracking equipment. And some of the evaluation criteria we use are things like driver fatigue, mental workload, situational awareness and usability.”

The original simulator was built using an old cab from a 1970s vintage Versatile tractor, but Case IH eventually donated a much more modern cab to replace it and allow for a more realistic version of a modern machine.

Research has shown as machines become more sophisticated and automated, operators’ understanding of how well they’re performing diminishes. But even automated systems need to be monitored to ensure machines work at peak performance as conditions change. If operators don’t know what’s going on, efficiency can suffer.

Understanding what types of systems best relay feedback from machines in the most efficient way is at the core of Mann’s research. His efforts have led to several improvements in systems over the years, as far back as the time when light bars were the most common method of GPS guidance.

As technology advances toward full autonomy, its supervisor may be operating a different machine at the same time he or she monitors autonomous equipment. That complicates things a little.

“If the intent is to incorporate real-time information, how do we go about doing that? That’s been our primary focus,” he added.

Even as the equipment industry moves steadily toward commercialization of fully autonomous equipment, the idea of farming with that kind of machinery doesn’t appeal to everyone. And perhaps, surprisingly, that includes Mann, who says he still likes to head back to the family farm for some old-fashioned seat time in a tractor or combine.

“I will confess that I’m not necessarily convinced all of this (autonomy) is a good idea,” he said. “Maybe my perspective is a little bit biased. I grew up on a farm. I look forward to the opportunity to get out on the tractor and get away from my computer and driving it. I’m not sure I’d feel the same way about going out to the farm sitting and watching it.”