When economist Joe Feyertag joined LMC International, everyone was focused on vegetable oils, he told CropSphere delegates. “Biofuel mandates were going up across the world.”

But Feyertag and his colleagues are doing quite a bit of work analyzing markets for lentils and other pulses these days, he said, as the plant protein market grows.

“That’s why Canada is going to play a very important role in the future in meeting that protein deficit that’s emerging around the world.”

However, what market exists for Canada’s growing faba green production is another question. To find some answers, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers commissioned LMC International to report on the market potential for fabas.

Read Also

Southern Alberta farms explore ultra-early seeding

Southern Alberta farmers putting research into practice, pushing ahead traditional seeding times by months for spring wheat and durum

- Read more: Would fabas fit in your crop rotation?

Export markets

Global demand for faba beans is now about four million tonnes, up from about 3.2 million tonnes in 1995. Nearly half that growth is in Ethiopia, Feyertag said. France, Morocco, Australia, Sudan, China, Egypt and Canada have also seen growth. Consumption has declined in the Mediterranean basin.

Despite that seemingly rosy picture, the global export market is limited. Feyertag said production has kept pace with demand in most countries. China’s production has declined. However, China used to be the world’s biggest exporter, so the country remains self-sufficient, Feyertag said.

That leaves Egypt, which has seen 107,000 tonnes of growth in consumption since 1995. But despite growing demand, faba bean production has declined significantly in Egypt, Feyertag said. That’s partly because the government subsidizes wheat, so farmers prioritize the cereal. Plus, there’s not enough arable land to expand production, he added.

“If you’ve been to Egypt, you know that all the arable land is around the Nile. And that’s exactly where they’ve built the cities.”

Egyptian importers prefer large, high tannin faba beans, which have better cooking quality. Smaller ones mean lower prices. “They really take their faba beans very seriously in Egypt,” said Feyertag.

Australia dominates the Egyptian faba bean market, producing higher-quality beans than many of its global rivals. The U.K. and France also have substantial shares of the market. France produces the least desirable beans of the three, and is dinged $60 per tonne compared to the Australian faba beans.

Should Canada focus on varieties coveted by global consumers? Feyertag doesn’t think so. Egypt will account for most of the future faba bean market growth, with the exceptions of small export markets in Morocco and Ethiopia, he said.

“If there is an export market that is concentrated in one single country, especially a country as politically unstable as Egypt, that’s probably a bad way to set up your industry,” he said.

Canadian exporters can fetch a premium if they sell between December and February, he said.

“And that’s not a coincidence. That is the space in between exports from the United Kingdom and exports from Australia.”

But sell outside that narrow window “then the premium falls right down.”

Domestic opportunity

Market opportunity for faba beans is much closer to home, in Feyertag’s opinion.

There may be opportunity for food consumption of whole faba beans in Canada, he said. Faba beans could also be fractionated to develop protein concentrates, although more research is needed.

“But if we do discover a functional nutritional advantage of using faba bean flour, faba bean protein concentrate, then that could potentially release huge volumes into the market,” said Feyertag. “That’s the wild card.”

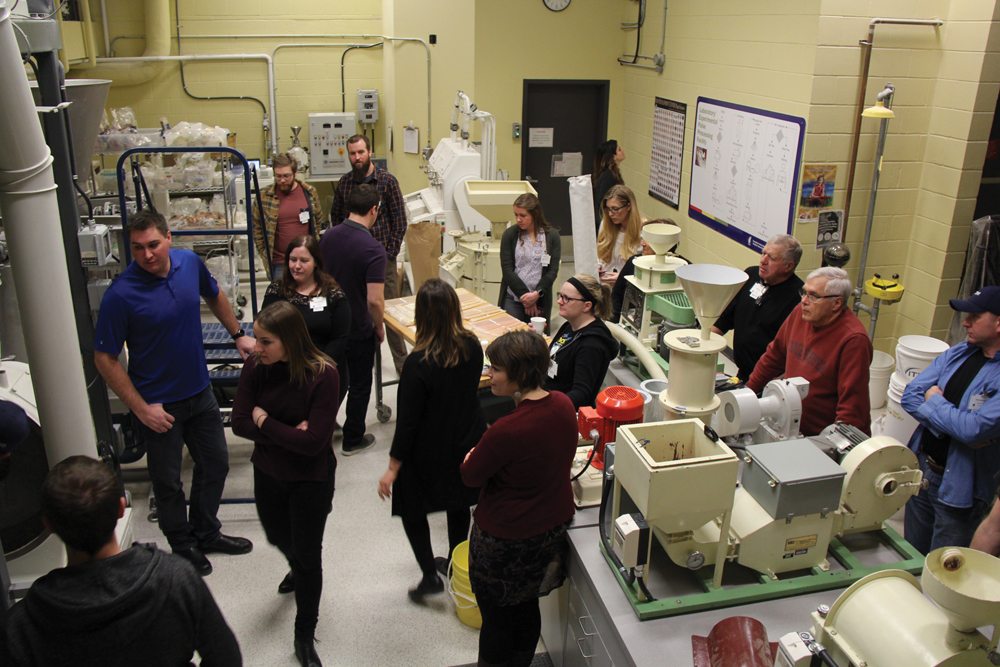

Feyertag said AGT Food and Ingredients, Canadian International Grains Institute (Cigi) and the Sask Food Industry Development Centre are exploring faba bean flour use.

The pulse flour market is only about 100,000 tonnes in Canada right now, Feyertag said. Many food manufacturers avoid it because it reduces baking quality. But consumers want plant-based protein and more fibre in their food, he said.

Entering the whole food market would require high tannin varieties. Tannin reduces protein digestibility, so it’s not desirable in animal feed. But consumers like the bitter taste.

However, the sector needs to beware favism, a hereditary disease that destroys blood cells. Faba beans are one of the triggers of the blood disorder in the unlucky people who are genetically prone to the condition. Most afflicted people have Mediterranean ancestry.

Favism is behind the faba bean consumption decline in the Mediterranean. Feyertag said faba bean breeders are working on varieties free from vicine, which activates the disease.

Faba bean protein would also face tough competition from soybeans. Soybeans are very high in protein and relatively cheap to produce, said Feyertag.

There are other challenges with faba bean protein. “The biggest problem we find is that you need to find value for the starch components,” said Feyertag.

Domestic feed market a safe bet

Adjust costs on a protein basis, and faba bean is a cheaper protein source than anything else, said Feyertag. “It’s already used by hog and poultry farmers. And feed millers buy it when it’s at a discount to peas.”

Vicine not an issue in livestock feed, according to research so far. Neither is lygus bug damage or bean size. Plus starch is seen as an energy source in the livestock industry, he added.

Snowbird is currently the dominant faba bean variety in Canada, and as a low tannin cultivar, it works fine for the feed industry. So does CDC Snowdrop, which sits at number two in Canada.

Feyertag pointed out that faba beans can be grown closer to the feed industry, making them cheaper to truck than soybeans in Manitoba or the U.S. Because faba beans can be grown north of the border, feeders could also avoid currency risks.

Just how big is the feed market? The hog and poultry market in Alberta and Saskatchewan could take between 220,000 and 500,000 tonnes of faba beans, depending on one’s optimism, Feyertag said. The Atlantic salmon feed market could also take up to 113,000 tonnes of raw material, which would be turned into protein concentrate.

“And then if you look at the beef cattle sector, then you’re talking about seven to nine million tonnes.”

Faba beans would be competing against other ingredients in a price-sensitive sector. But Feyertag doesn’t see anything stopping faba beans from competing.

Feyertag took questions from the floor at the end of his presentation. Brad Goudy, a marketing consultant from Melfort, said that he’d put together a production contract for faba beans as feed. He asked how they could build a good base for a feed market.

“The real solution to the feed market is volume,” Feyertag said. “(Feeders) can’t buy a tonne of faba beans here and there. They need tens of thousands of tonnes.”

Faba bean growers would have to accept lower prices until feed mills realize faba beans are a good source of protein, and the volume reaches the market, Feyertag said.

“Once that happens prices will adjust on a protein-level basis, as long as there aren’t any other disadvantages of using faba beans against peas or against soybeans, which as far as I’m aware, there aren’t.”