Glacier FarmMedia — A company in the U.S. is commercializing a new falling number test it believes is more accurate than the existing method.

Amber Hauvermale, an assistant research professor in the department of crop and soil sciences at Washington State University, developed the test in collaboration with several other organizations.

It was in response to the outcry from growers in the Pacific Northwest region following a 2016 disaster in which much of its soft white wheat crop was severely discounted due to poor falling numbers.

Those results were in part due to harvest rainfall causing sprouting — a legitimate concern for the baking industry — but a cold snap earlier in the year during the soft dough stage of development had also induced alpha-amylase expression.

“It’s not a sprouting event, but it can cause a decrease in falling number due to alpha-amylase expression,” Hauvermale says.

In other words, some growers were being unfairly penalized for a condition that did not harm the baking performance of the flour made from that wheat.

That prompted calls for a new testing methodology to replace the Hagberg-Perten falling numbers test developed 70 years ago.

The existing test is based on how long it takes a plunger to fall through a test tube of wheat gravy — an indirect way of testing for pre-harvest sprouting damage.

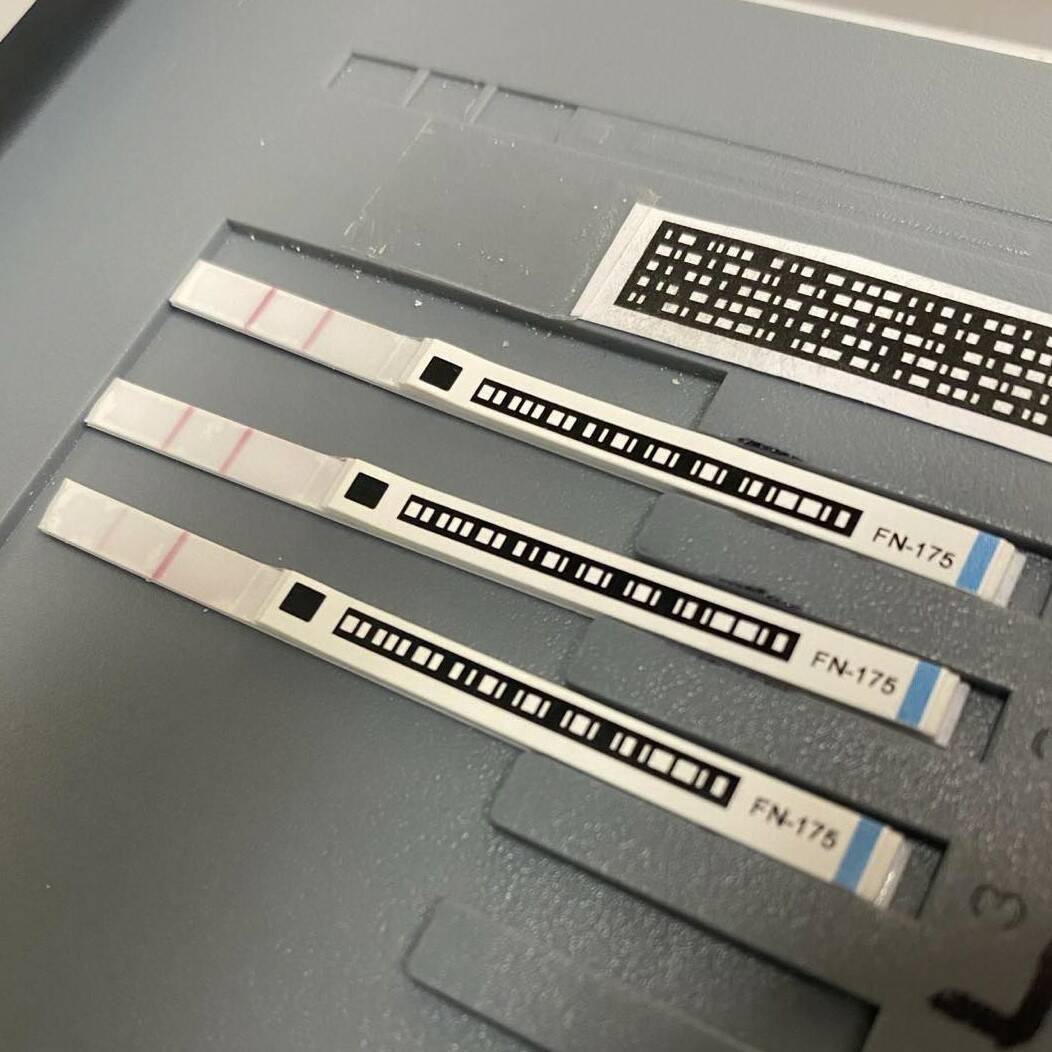

The new test uses dipsticks to directly measure alpha-amylase activity. The dipsticks are then read with a flatbed scanner that provides a falling number estimate.

The new methodology has been tested against the old methodology at the plot level, in the U.S. elevator system, and by the Wheat Marketing Center in Oregon.

“We did see equivalent performance essentially at those three different levels of testing, so we were pretty pleased with that,” Hauvermale says.

Jayne Bock, technical director with the Wheat Marketing Center, says the problem with the existing test is its margin of error.

There are substantial price discounts in the U.S. Pacific Northwest for wheat samples that have a falling number below 300 seconds.

The existing test has a margin of error of plus-or-minus 20 or 30 seconds, so a sample that has a true value of 300 seconds may have a result that reads as low as 270 seconds or as high as 330 seconds.

Considering price discounts often start at around 298 seconds, “to have a cutoff that’s so quick after 300 seconds, when the accuracy of the test doesn’t really allow for that, is quite punitive for growers,” she says.

Hauvermale says a new test could save farmers “hundreds of millions of dollars” in years such as 2016, with widespread weather damage across large swaths of a growing area.

There is potential for the test to be further refined so it can be used directly on farms where growers might be able to improve falling number levels by storing the grain for a while.

Bock found the new test delivers falling number values nearly identical to those from the old test — and in some cases is proving to be more accurate, such as with samples of wheat that experienced a severe freeze event in the Pacific Northwest in 2024.

The existing test showed wheat had falling number values in the 260- to 270-second range. The test was sensitive to whatever happened to the starch during the freeze.

However, the new test resulted in values exceeding 300 seconds.

The wheat samples were subsequently used in baking tests, which showed the wheat flour performed perfectly, indicating the new test had it right.

EnviroLogix is the company commercializing the new test, which will initially be used for testing soft wheats. The Maine company is working with other partners to calibrate the test for other classes of wheat.

Hauvermale says the hope is to eventually commercialize the new test in Canada and elsewhere around the globe. She confirmed there have been conversations with the Canadian Grain Commission.

A spokesperson for the commission said its scientists are aware of the test and are monitoring it.

Hauvermale says the ultimate goal is to use the data from the new testing methodology to help breeders create new lines of wheat less susceptible to events that cause low falling numbers.