matt-johnson-m3aerial

Matt Johnson is the owner of M3 Aerial Productions, based out of Winnipeg. Farmers can buy their own drones, or hire someone like Johnson to fly their fields.

Photo: Matthew Johnson, M3 Aerial Productions

ag eagle and inspire 1

The yellow machine is a fixed-wing drone called the AgEagle RX60, worth about $25,000. The DJI Inspire 1 is a quadcopter, worth $10,000 to $12,000.

Photo: Matthew Johnson, M3 Aerial Productions

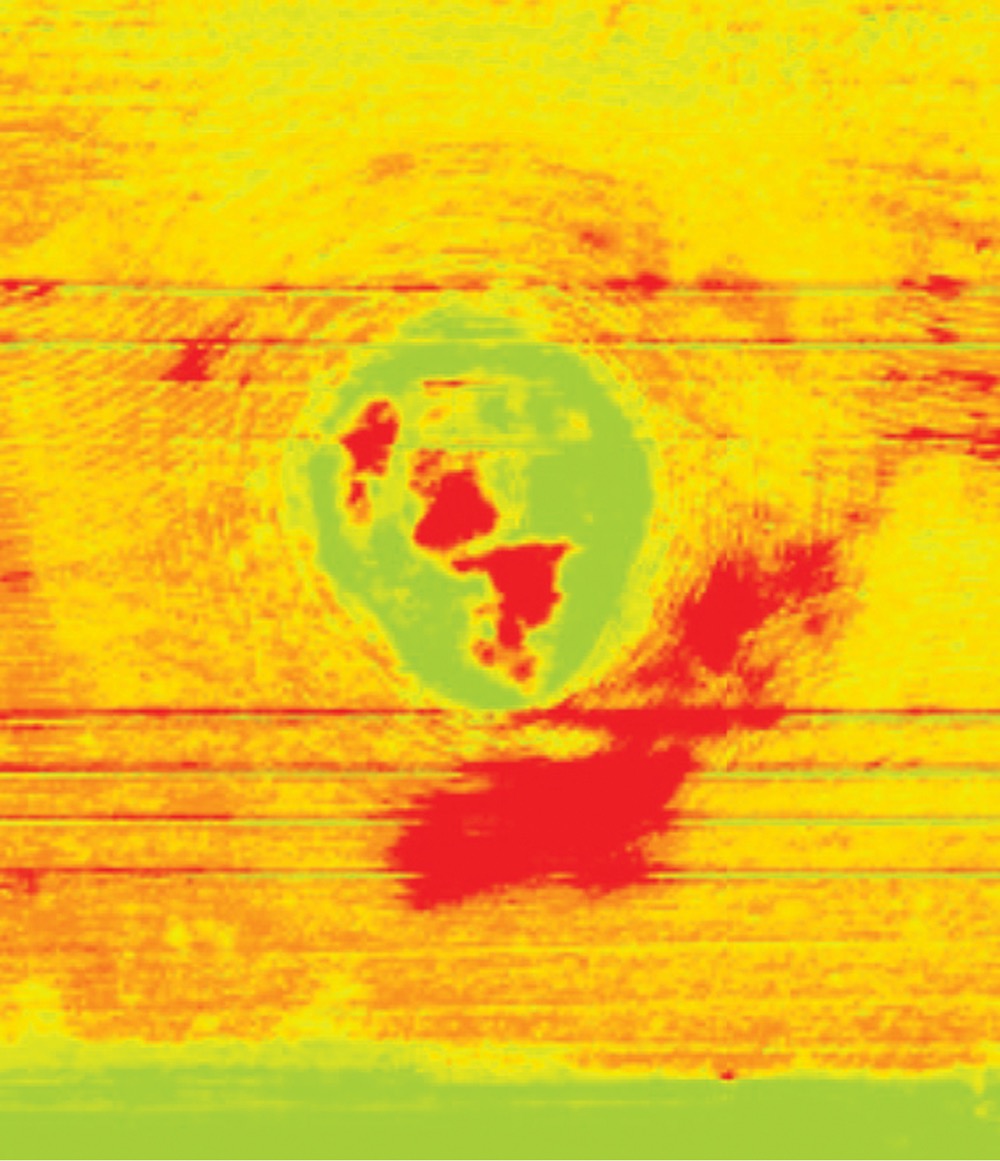

peas-infrared

In this digital image of a pea crop, the green area shows a depression where weeds flourished.

Photo: Matthew Johnson, M3 Aerial Productions

ebee-fixedwing-drone

The eBee is a fixed-wing drone with a styrofoam body. It takes to the sky easily.

Photo: Matthew Johnson, M3 Aerial Productions

quadcopter

Quadcopters can take high-resoloution photos from a few feet above the crop, capturing the striations on the plant leaves. They can also fly as high as 400 feet, snapping general pictures to correlate with the NDVI.

Photo: Matthew Johnson, M3 Aerial Productions

Farmers are buying drones, but often they can’t use the technology to its full potential, says Matt Johnnson. And new drone operators need to research the options available and safety requirements before flying, he adds.

Johnson owns M3 Aerial Productions, based in Winnipeg. A math teacher by profession, he started using drones for real estate photography. But after doing more research, he realized the technology provides more return on investment in the agriculture industry. In 2016, he launched the agricultural side of the business.

Farmers can buy their own drones or hire someone like Johnson to fly their fields. “I can show them what’s going on in their crops, and they have to be able to interpret it,” he says, adding he’s not an agronomist.

Read Also

Right stuff, wrong time: How a team in Ontario developed the highest-capacity rotary combine of its day

Innovations by a team in Ontario in the late ’60s would lead to the production of the biggest rotary combine of that time. Then the manufacturer went bankrupt.

While Johnson has worked with individual farmers, he prefers to work with agronomists or seed companies. This summer he did some work with General Mills, the University of Manitoba, Alliance Seeds, the Manitoba Forage and Grassland Association and independent agronomists.

How it works

Johnson typically uses a fixed-wing drone called the AgEagle RX60. The drone has a GoPro camera with a special lens to take infrared imagery. It flies about 500 feet above ground level in a grid pattern, snapping a photo every 1.5 seconds. That creates about 500 pictures per quarter. After flying the fixed wing, he might use his quadcopter to zoom in on specific areas in the field.

Johnson then uploads those images into a program that stiches all the images together, pixel by pixel, into one cohesive image. The software also creates a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), which paints the field in a spectrum ranging from red to green.

Plants that are healthy — growing and photosynthezing — show up as green on the imagery. Red areas indiciate plants that aren’t photosynthesizing as much, and so are likely struggling for some reason.

But green patches can also indicate weeds, Johnson says, so it’s important to compare the imagery to “the truth on the ground.”

This spring, Johnson flew a canola field with two different drones, using multiple sensors.

“And the results that we got were very interesting because there was less growth happening in a strip about 200 feet wide that went right across the quarter section, right above where an underground pipeline was.”

An agronomist would need to diagnose the specific problem and offer remedies. Johnson says they couldn’t see any differences within the crop with the naked eye, perhaps because the crop was at the six-leaf stage.

Johnson thinks NDVI imagery could also help farmers with harvest timing. He flew some trial plots this summer, close to harvest. While some plots looked like they were ready to harvest, the NDVI imagery revealed that they were still actively growing. Other areas appeared yellow on the NDVI, which was a green light for harvest, he says.

Johnson sees NDVI as potentially helpful when making short-term decisions such as where to apply fertilizer. He could also see it helping with long-term planning if farmers collected NDVI of crops just before harvest each year.

Along with NDVI, farmers could also use drones for digital elevation mapping. Johnson says that based on conversations he’s had at farm shows, frmers seem more interested in digital elevation mapping than NDVI.

Drone options

Farmers considering investing in their own drones need to keep a few things in mind when weighing the pros and cons of different models.

Johnson sells fixed-wing AgEagle drones (now distributed by Raven Precision), but he’s also a fan of eBee’s fixed-wing drone.

The AgEagle is more rugged and handles windy conditions, he says. “It’s had some pretty rocky landings.”

The eBee has a styrofoam body and is less sturdy, but one of its advantages is that it takes to the sky more easily. You just hold it and shake it to launch. “The propellor starts and then you just throw it,” Johnson says,

The AgEagle, on the other hand, needs a slingshot to launch, which requires a little more setup time.

Quadcopters are also an option. They can take high-resoloution photos from a few feet above the crop, capturing the striations on the plant leaves. They can also fly as high as 400 feet, snapping general pictures to correlate with the NDVI.

But a fixed wing can cover ground much more quickly than a quadcopter, and use much less battery power, Johnson says. In fact, a quadcopter would probably take about three batteries to cover one quarter, he says. “And three batteries cost close to a thousand dollars.

As the technology improves, drone prices are dropping. Johnson’s quadcopter, a DJI Inspire 1, is a $10,000 to $12,000 touch, but it includes a $5,000 sensor and eight batteries. The fixed wing was $25,000, he says.

Not a toy

It’s easy to get carried away with a new drone, says Johnson. “But it’s not a toy. It’s an aircraft.”

People using a drone for work or research, or flying a drone over 35 kg, generally need a Special Flight Operations Certificate from Transport Canada.

Johnson’s certification allows him to fly up to 500 feet above ground level, which edges manned aircraft space, he says. People without a certificate must keep their drones within 300 feet of ground level. Johnson recommends farmers or others interested in flying drones check the safety information and regulations on Transport Canada’s website.

Drones can be a risk to other aircraft, especially low-flying cropdusters. Johnson checks in with NAV Canada, the agency that manages air space, before each flight. Sometimes NAV Canada has him file a Notice to Airmen, which tells pilots where and when he’s operating, how high he’s flying, and what the drone looks like.

But Johnson doesn’t think all cropdusters check the notices. Quite often a cropduster has flown through the quarter his drone is on, coming in as low as a hundred or two hundred feet.

“They’ve never had to worry about (drones). They’re flying in rural areas that other planes are not operating in.”

So before flying, Johnson also checks if there are air strips or cropdusters in the area. “I co-ordinate with them, let them know exactly where I’m going to be operating and when I’m going to be there.”

Johnson thinks farmers and other drone operators should do their research before flying.

“If it keeps going the way it’s going, something bad is going to happen.”

For more information on drone safety and regulations, visit Transport Canada’s website.