When Brian Beres left a field day at Indian Head, Sask. a few years ago, he didn’t expect the real show-and-tell would happen afterward. But after the field day, farmer-inventor Jim Halford had something else in mind.

“He said, ‘Hey, I gotta show you something at my farm,’” Beres, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, recalls. “So he grabbed me, jumped in his truck and we drove over.”

Halford is no ordinary farmer. He’s a zero-till pioneer and inventor. He made headlines in 2007, when he sold the technology for the ConservaPak air seeder to John Deere. He was inducted into the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame in 2021.

Read Also

Farm equipment market unlikely to pick up

North America’s farm machinery sales have been slow and uncertain thanks to tariffs and trade disruption. There’s not a lot of hope for change in 2026.

Halford showed Beres a retrofitted swather with a spray boom and tank, and a cart towed behind for water and herbicide solution.

“He’d done the homework,” Beres says. “It worked.”

What Halford had done — spraying pre-seed herbicide at the same time as swathing his canola — wasn’t just a clever labour-saver. It was a potential solution to one of the biggest obstacles preventing more Prairie farmers from growing winter wheat: timing.

From Down Under to the drawing board

Halford first got the idea after visiting Australia. It turns out Prairie farmers aren’t the only ones looking for ways to save time at harvest. Some innovative farmers down under were using a technique that let them spray and swath at the same time.

“I didn’t see it actually operating — they just talked about it,” Halford says. So, when he got back to Canada, he got to work on a prototype based on what he’d heard.

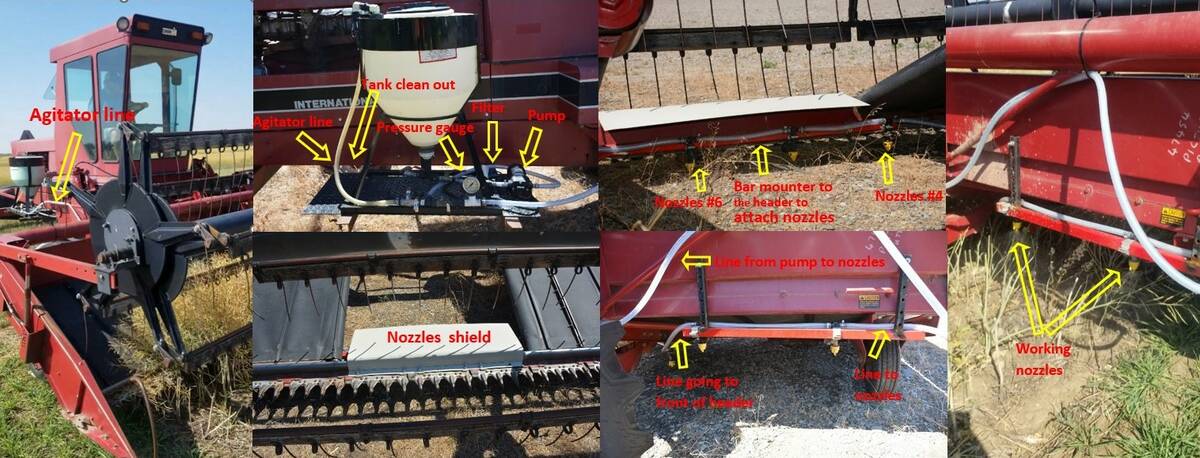

He retrofitted his self-propelled swather with a spray boom that reached under and behind, where the swath dropped. He towed a two-wheeled tank behind to carry enough water to make the setup work at field scale. He was convinced it could offer a better way to control weeds and preserve soil moisture at a critical time of year, when growers are swamped with harvest and field work.

“We realized the benefits of it, and that’s why we were working on it,” Halford says. “If you knock your weeds out as soon as you get an opportunity, you’re going to start saving moisture.”

His goal wasn’t to launch a product — though he said that might have happened if he’d stayed in the seeder business, but that option wasn’t available once he sold the ConservaPak seeder technology to John Deere.

Some assembly required

While both Halford and Beres say the retrofit isn’t especially complex or costly, the study didn’t offer step-by-step retrofit instructions. That said, Halford’s prototype proves it’s doable for those willing to experiment with their equipment.

“You’ve just got to get the boom under the centre, where your crop is coming out of the swather,” Halford says. “We had a tank on a cart behind, and a boom tucked underneath — even under the middle.”

The key, he says, was making sure the boom delivered consistent spray coverage under the swath.

After seeing the prototype, Beres folded Halford’s design into a funding proposal for a sequencing study with winter wheat and canola.

“This is one of the best examples I’ve seen of how farmer-led ideas can feed into large-scale agronomic research,” Beres says. “Jim showed us it could work at scale, and our job was to build the science around it.”

Eliminating a field pass

The study focused on finding ways to streamline fall operations so farmers could more easily seed winter wheat following canola. In many regions, that tight window is a key reason growers hesitate to plant winter cereals.

To address that squeeze, researchers explored whether the swathing and pre-seed herbicide pass for winter wheat could be done at the same time, using Halford’s concept. Across multiple sites, they retrofitted field-scale swathers with onboard spray systems.

For their plot-scale equipment, Beres’ team was able to mount tanks directly on the swather. Beres noted they were still using commercial swathers on their big agronomy plots. They were just narrower, at 15 feet wide. And the retrofit was done at a modest price.

“The only difference between us and Jim is that we could mount the tank onto the swather,” he says.

It worked. The study showed strong weed control and no need for an additional fall herbicide application.

And importantly, when researchers worked with the Canadian Grain Commission to test the highest-risk samples, they found no glyphosate residue in most of the harvested canola. In one or two cases, trace amounts were detected, but well below the maximum residue limits (MRLs) set by the government of Canada to protect market access.

Yield bump, fewer passes

One surprise was how well winter wheat performed after swathed canola, compared to straight cut.

“We saw a yield bump with swathing,” Beres says. “We don’t know why, but it’s probably related to conserving soil moisture.”

Halford’s own experience backed that up. Though he didn’t conduct formal trials, he left unsprayed check strips in his fields and says the benefits were clear.

“The weed control was excellent,” Halford says. “We saw a big difference, especially with fall-germinating weeds that would otherwise be taking up moisture.”

Beres emphasizes the system also has potential to reduce herbicide use beyond the fall season. Because winter wheat is highly competitive, in-crop spraying often isn’t needed — particularly if the fall application is well timed.

“If you did something like a 2,4-D application in mid-October, when winter annuals start to emerge, that might be all you need,” said Beres. “We’ve shown that in multiple studies.”

Swathing versus straight cutting: the debate isn’t over

For years, western Canadian growers have increasingly moved away from swathing in favour of straight cutting. This is especially true in brown-soil zones where crop height and yield potential tend to be lower. But Beres said attitudes may be starting to shift.

“We’re seeing some pushback,” Beres says. “Guys who tried straight cutting are going back to swathing. When you’ve got a heavy crop, it can be hard to get the timing right across the field.”

That inconsistency can delay harvest and jeopardize the window for planting winter wheat, especially in regions where fall weather tends to be less forgiving.

The study also addressed a common hesitation about swathing: concerns about pod shatter. But researchers used pod shatter reduction hybrids and saw no issues in either standing or swathed canola. “We really wanted to verify that those traits work when integrated into a systems study, and they do,” Beres says. “It’s one more concern we were able to take off the table.”

An idea with agronomic legs — even as research wanes

Though Beres says the swather-sprayer concept is ready for farmers to test on their own operations, he doesn’t expect much further work on winter wheat out west — at least not any time soon.

“There’s a lack of interest in funding winter wheat agronomy, largely because of the low acreage versus spring wheat, so impact from agronomy can be tenfold or more in spring versus winter wheat, so it makes more sense to fund and conduct research in a spring wheat system,” he says. “This study, and another we published earlier this year, are kind of the swan song for large-scale winter wheat agronomy in our program.”

That other study looked at crop rotations leading into winter wheat and showed that pulses like lentil and soybean actually outperform canola in some cases. Like this study, it confirmed winter wheat’s strong fit in Prairie systems, even if it’s often overlooked.