A new partnership between Geco Strategic Weed Management and Gowan Canada is giving Prairie farmers a reason to take another look at predictive weed control.

The partnership pairs Geco’s predictive mapping tools with Gowan’s line of soil-applied herbicides in a collaboration aimed at helping farms take a more deliberate, patch-based approach to weed control over multiple seasons.

Why it matters: Seeing weed pressure ahead of emergence can make herbicide decisions more targeted and cost-effective.

Read Also

Deere expands spot spray system for small grains crops

John Deere says it has expanded the See and Spray system’s functionality to other crops. For the 2027 model year machines, it will be compatible with wheat, barley and canola.

Geco’s announcement includes two offerings tied to the partnership. The company is launching a new three-season predictive-mapping subscription, and growers who sign up through a Gowan representative will receive one additional field map at no extra cost.

“Our technology enables the question: If you could know where your most problematic patches are and where they are spreading to, what could you do differently? That’s what our technology makes possible,” said Greg Stewart, CEO of Geco.

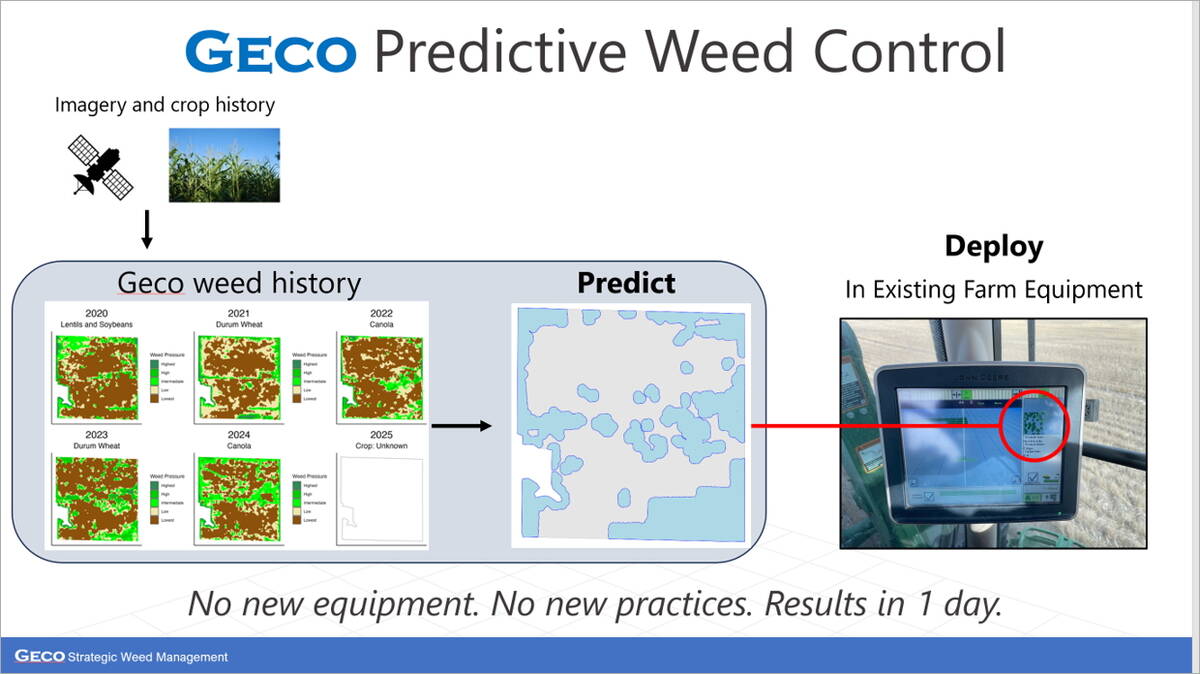

How predictive mapping works

While blanket applications and spot sprayers respond to weeds already visible in-season, predictive mapping works ahead of emergence by using multi-year imagery to identify the areas most likely to develop patches. That allows farms to be proactive with treatments, rather than reacting after they’ve already gained ground.

A grower wanting a map begins by sharing a field boundary with Geco, often through a platform like John Deere Operations Center. If they don’t have a boundary available, Geco can make one for them. From there, Geco pulls every usable satellite image of that field from the last five growing seasons and runs them through tools designed to distinguish crop from weeds across the full season.

That multi-year history is what drives the prediction. Stewart said the key isn’t ultra-high-resolution imagery as much as having dozens of images per season and several years of history to reveal how weed patches shift over time.

The history shows where weeds tend to emerge early or flush late, and where patches persist. The resulting prescription can be exported straight into a sprayer, granular applicator, drill or variable-rate seeding tool.

“We look at a field, understand where weeds have been and where they’re going, and from there the farm decides what to do,” he said.

Geco has calibrated its system by comparing predictions against drone imagery, spot-sprayer data and human scouting across many fields.

Because the algorithms used to make these calibrations and predictions are proprietary, Stewart was tight-lipped about their inner workings. But while they play a big role in the process, he says the real challenge is fitting the technology into a farmer’s season.

“It’s not usually the math that breaks these technologies,” he said. “It’s how well you solve a real-world problem.”

That means making sure the system fits farm reality. It must mesh with timing at the end of the season and fold naturally into a grower’s weed-control plan. Those practical points tend to matter more than the complexity of the algorithm.

That’s also where partnerships come in. Predictive maps don’t work in isolation; they need to line up with the herbicides and practices growers are already using in the field.

Many early adopters were already using chemistries such as ethalfluralin and triallate (the active ingredients in Gowan’s Edge and Avadex) on their worst kochia and wild-oat patches. Those products are expensive to blanket across entire fields, and predictive maps help target them only where they’re most likely to deliver a return. So, the collaboration made sense for both companies.

![[OPTIONAL] Geco’s field footprint in fall 2025, with most mapped acres clustered in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Credit: Geco](https://static.grainews.ca/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/02182350/226152_web1_Geco-fields---October-2025.jpg)

But herbicides are only one part of the equation, said Stewart. Once the map is made, growers still need a plan for how to use it: which products to place where, when to increase seeding rates and how to tackle the “problem-child” areas that keep showing up year after year.

“It’s the agronomist and the farmer who put together that strategy,” he said.

How agronomists use the technology

One of those agronomists is Rob Warkentin of Davidson, Sask., who has helped several farms work predictive maps into their weed-control plans.

For Warkentin, predictive mapping works best on fields with well-defined patches like those same “problem-child” zones mentioned by Stewart. Once he receives a map, he reviews it with the grower to confirm the predicted zones match field history and scouting. He then adjusts rates, creates the prescription file and loads it into the sprayer or applicator.

There are still some practical limits — the kind Stewart refers to when he talks about real-world barriers. For example, some older spreaders can’t run prescription maps. Fortunately there is an easy workaround: growers can load the files into Google Maps. However, Warkentin says timing is a more stubborn problem for farmers.

“The best time to look at these maps is after harvest, but that’s also the busiest time of year,” he said. “By the time fall work is done, there’s very little time left to get maps made up and implemented.”

For farms using higher-value soil-applied products, the economics work well. Targeting only the worst 20 or 30 per cent of the field makes premium herbicides more economical and reduces total chemical use. Farms using lower-cost products may see less financial benefit, since the price of generating a prescription can outweigh the savings from variable-rate application.

However, Stewart noted that most growers use the maps to intensify control in the toughest patches — not necessarily to cut total inputs.

Either way, Warkentin says growers who used the maps were pleased with the results.

“The system isn’t perfect, and producers know there will be a few small misses,” he said. “But overall the people who’ve used it have been happy with the results.”

The science behind patch prediction

Stewart says much of Geco’s system grew out of earlier work in greenhouse pest modelling and even pandemic-spread research. The ebb and flow of insects in a greenhouse, or disease outbreaks during a pandemic, mirror how weed patches behave across a field, and understanding those patterns is key to making predictions.

For weed scientist Charles Geddes of AAFC Lethbridge, predictive mapping fits within a broader integrated weed management approach. He sees it helping growers make more deliberate decisions about where to invest their time, herbicides or cultural practices.

“I see this as another tool in the toolbox farmers have at their disposal,” he said.

Weed pressure is becoming harder to manage due to expanding herbicide resistance and weather variability that affects herbicide performance. Geddes says predictive mapping can help farmers plan where residual herbicides or added competition may provide the biggest returns. Using herbicides that stack multiple modes of action can be costly, especially on dryland farms, and applying them across full fields isn’t always justifiable.

“Predictive mapping lets farmers target herbicides or other practices where they’ll have the greatest impact,” Geddes said. “That can go a long way toward managing both costs and resistance.”

He also notes the technology adds some complexity. Prescription mapping requires growers to manage another layer of planning at a time of year when workloads are already heavy. That may limit adoption for some operations. But he expects interest to grow as farms gain experience and as more tools in crop production move toward AI-driven decision support.

Looking ahead

To date, Geco has evaluated more than 300 Prairie fields, building a clearer picture of how weed patches behave from year to year. The company has also been running pilot projects in the U.S., Australia, Europe and South America to discover how transferable the approach may be. But Stewart says the long-term focus remains firmly on Western Canada, where the vast majority of its customers currently reside.

That Prairie focus shapes where the technology goes next. Stewart says the company is now putting more emphasis on building partnerships with local retailers, agronomists and farmers to support longer-term, multi-season weed strategies. The Gowan partnership is just one example.

“We’re starting to partner with other retailers and independent agronomists across the region,” he said. “We’re really developing those relationships as much as we can these days.”

CORRECTION, Jan. 2, 2026: On page 5 in the Dec. 31, 2025 print edition, the final eight words of this article were accidentally chopped out at the end. We regret the error.