Greg Stamp likes to keep on-farm field trials on his southern Alberta farm simple.

If he’s evaluating the effectiveness of a new fungicide or herbicide, for example, he’ll make two or three passes with the sprayer with the new treatment and then two or three more passes for the check strip (no new product). He’ll ground check the strips after the treatments for any visual difference, but the real test comes at harvest when he can measure the results.

“We plan for just one treatment in each of the on-farm trials,” says Stamp who is part of the family run Stamp Seeds farm at Enchant, southeast of Calgary. “If you try to compare two or more changes in your program in one on-farm trial it is too hard to tell which treatment really is making a difference.”

Read Also

AgraCity’s farmer customers still seek compensation

Prairie farmers owed product by AgraCity are now sharing their experiences with the crop input provider as they await some sort of resolution to the company’s woes.

He used to just evaluate combine yield monitor data, and while that can be useful, he also found it limiting. He now uses a grain cart weigh wagon to evaluate on-farm trials. “The weigh wagon is much more accurate,” he says. “Data from the yield monitor is sometimes hard to read, and it has trouble showing you small changes in yield. So now with the weigh wagon we can harvest crop from the test strips as well check strips and have a very accurate comparison.”

Stamp says it is important to have replicated test strips when evaluating a product or treatment, and also important to look at more than one year of data. “You can have different growing season conditions which can make a difference in the results and even the time of seeding can make a difference,” says Stamp. “We have seen that one year in comparing two seed varieties, for example, that year A out performs B, but the next year you seed a bit earlier and B out performs A. So you need to look at this information over at least two or three years before you draw real conclusions.”

When collecting yield from test and check strips, he runs the combine down the centre of strip to collect the “cleanest” grain he can for weighing, which helps to eliminate influences on the edge or the ends of the strip that could impact the results.

Proper plan of attack

The procedure Greg Stamp follows for conducting on-farm trials is on track with the approach recommended by long-time Alberta Agriculture researcher Ross McKenzie, of Lethbridge.

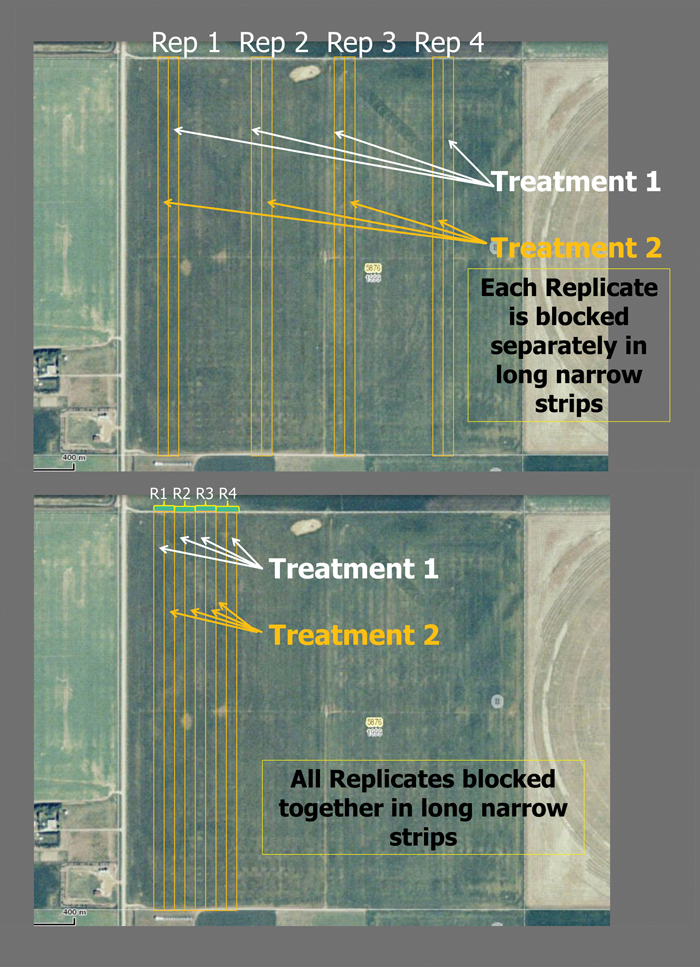

“The best approach with on-farm trials is to keep it simple and make sure it is replicated,” says McKenzie, now retired and a consulting agronomist. “A single side-by-side field comparison has some value but it doesn’t tell you the real story. Some guys like to take a 160 acre field and treat 80 acres with a new product and then leave the other 80 acres as the check. But unless you have extremely uniform field conditions how do you know that any difference you see isn’t due to some other change in topography, or soil type, or whatever.”

And he cautions too, that some farmers try to load too many new treatments in one on-farm trial. “If you make two or three or more changes in a treatment and compare that your standard practice, how do you know which one of those new treatments is actually making the difference? Maybe one is making all the difference and the others have no effect. So focus on one change at a time.”

McKenzie recommends whether evaluating a seeding or crop protection practice to make anywhere from two to four passes, one or two widths of the implement being used the full length of the field. And then next to that make two to four passes the same width as the untreated check strips. Identify those strips with your GPS and then harvest accordingly.

“There can be variables affecting results on the headlands or on the edges of your trial strips, so combine the centre of the strip to remove as many variables as possible,” he says. “If the sprayer is 60 feet wide and the combine header is 30 or 35 feet wide, run the combine down the centre of the 60 foot strip to get the most accurate yield.” And plan on conducting the trials for at least three or four seasons — exposing the treatment to variable growing conditions — to get the best read on whether or when a product or treatment is effective.

Farmers who have some basic skills in working with statistics are probably able to evaluate their own yield data information, but they can also get the advice of provincial agriculture offices, Agriculture Canada offices, local applied research association specialists, or private agrologists for help on how to read and evaluate the information.

“It is important to replicate the on-farm trials in a particular field, and for best results pick areas of the field that have the most uniform soil conditions and topography,” says McKenzie. If a large portion of a field has lighter sandy soil, conduct one on-farm trial in that area, and in another area of heavier soils make a second on-farm trial there.

“Keep it simple, make sure it is replicated and as uniform as possible to get the most useful information,” he says.