To retain a foothold in the pull-type combine market in the 1980s, White Farm Equipment needed to create an all-new model with rotary threshing technology. The 9550 was to be that model. It would “out spec” International Harvester’s 1482, which dominated the pull-type market in Western Canada at the time.

That meant it would be a very big machine for the era.

“The combine was designed to be powered by a tractor with a minimum rating of 150 horsepower, but it was also recognized that 180 to 200 horsepower would be required to make use of the maximum combine capacity,” says Murray Mills, a former engineer who worked at White Farm Equipment’s combine engineering offices in Brantford, Ontario, in the 1980s. “A large tractor was also needed to handle the weight of this machine, especially when the 225 bushel grain tank was full. In fact, it was soon determined that brakes would be required for a machine of this weight to prevent the tail wagging the dog.

Read Also

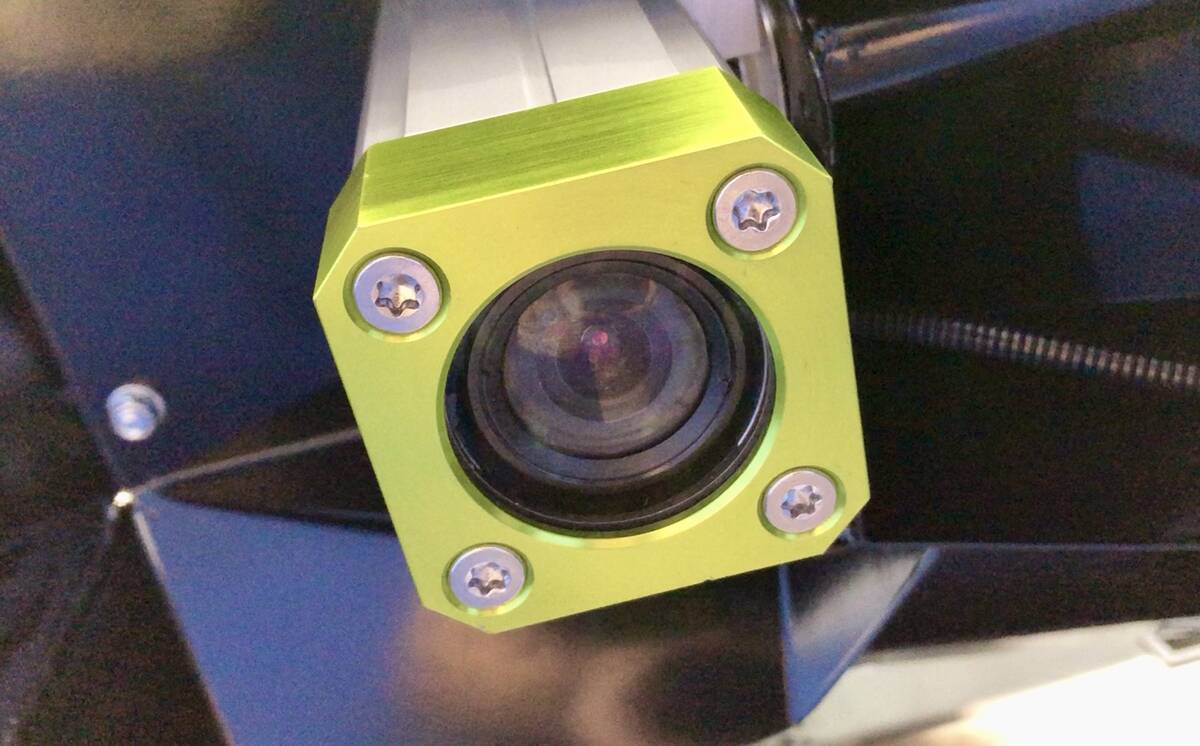

Yield EyeQ camera system measures harvest loss at header

Harvest equipment manufacturer Geringhoff won a silver Innovation Award at Agritechnica for its Yield EyeQ camera system, meant to help farmers measure grain loss at harvest.

“Oh, It was heavy,” agrees Dave Houston, who was project engineer on the 9550. “Loaded, I think it weighed over 30,000 pounds.” There were some in the company who thought the 9550’s size and weight made it impractical to produce. “It was just too big,” he adds.

Compared to the model 8650, the conventional pull-type combine White was already selling in Western Canada, the 9550’s size was impressive.

“(The 8650) weighed about 12,000 pounds without pickup and required a tractor with 100 horsepower or more at the PTO for power,” says Mills. “Fully loaded with 150 bushels of wheat and with a pick up installed the weight would be about 22,000 pounds. The 9550 rotary, in comparison, weighed about 21,000 pounds empty with header and pickup, so loaded with 230 bushels of wheat would weigh close to 35,000 pounds.”

More from the Grainews website: The beauty of the harvest

White’s plan for rotary combines

Creating the 9550 was part of White’s five-year strategic plan to offer a full line of rotary combines to the market by 1986. There would be three self-propelled models, the 9720, 9520 and 9320. And there would also be the 9550 pull type, which would have the same specifications as the mid-sized 9320 self-propelled.

To save design costs and make for efficient production, engineers wanted to build the self-propelled 9520, on which the 9550 would be based, in a way that allowed it to share 20 per cent of its parts with other machines already in production. They could save even more money by carrying that idea on to the 9550, having it share as many parts as possible with the 9520. One of them would be the header.

“Many of the pull-type combines at that time were fitted with offset headers to narrow the footprint of the tractor-combine combination and consequent drag on sidehill operation,” says Mills. “This, however, not only required a special header for PT combines but often resulted in feeding problems in heavy swath conditions. White engineers decided to use a centre-feed header. This allowed the use of the same 13-foot pickup and direct-cut and grain headers used with the SP combines.”

The new White combine line was to incorporate some cutting-edge advances, as well.

“The other main feature of this combine design, in addition to the rotary threshing and separation, was the hydrostatic rotor drive,” explains Mills. “This feature allowed the operator to clear a slugged rotor by rocking the rotor back and forth while sitting in the tractor seat. The machine was fully monitored and controlled by a system of sensors and controls wired to a monitor box in the tractor cab.”

To test the combine’s design and get ready for production, White engineers built several test stands and one field-ready prototype 9550. But doing so involved much more than putting a hitch on the 9520’s existing threshing mechanism.

“That’s the way it started out,” recalls Houston. “That’s basically the way you start. You take the self-propelled, put a new frame and hitch on it, and away you go. The 9520 was a smaller version of the 9720. The basic similarity was it had a grain tank with saddle tanks on it (to expand its capacity). But the problem was these saddle tanks were difficult to work around. They were portions of the grain bin that extended down on both sides of the main frame. So we eliminated them. The other thing I knew from experience on the 9720 was the factory on Mohawk street had a difficult time producing them.

“So we tried to get the (grain tank) capacity we wanted without these saddle tanks, which wasn’t the easiest, because they held quite a bit of grain, and without them it affected the combine’s centre of gravity. We were trying to get 250 bushel capacity. But without those tanks it reduced that by 20 or 30 bushels. Anyway, we (eliminated them), and the decision wasn’t made lightly.”

“The decision to redesign the grain tank reduced the commonality with the 9520 and required changes to a number of the drives,” says Mills. “Management had wanted the the family to look alike but the redesign necessitated changes in the appearance of this machine.”

“When this one came out it didn’t look the same (as the other models) at all,” adds Houston.

Nevertheless, development of the prototype moved forward and it was field tested.

“It was run here, in Southern Ontario first,” says Mills of the initial field trials on the prototype. “Then it went out west to Saskatchewan.”

But mid way through its five-year plan, White decided to abandon the proposed mid-sized, self-propelled 9520 because it offered only a small capacity advantage over the smaller 9320, not enough to justify the much higher price White would have to sell it for to meet production costs. So the decision was made to go with only two self-propelled models. That affected work on the pull-type, which, of course, was based on the 9520.

White’s plan B for the pull-type project was to start over and this time model it after the smallest of the two remaining self-propelled models, the 9320, which the company still intended to build. But that combine still only existed on paper. There was a lot of work to do before another version of the pull type could be based on it.

In the next issue we wrap up this series by revealing what went wrong with the project.