Tracking an outbreak of bovine tuberculosis through southeastern Alberta and southwestern Saskatchewan is still expected to lead to more quarantines of more Prairie cattle ranches, though no new controls have been imposed since before Christmas.

As of Wednesday, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency reported no new cases of bovine TB in its investigation, beyond the six cattle it had confirmed as TB-positive by mid-November 2016.

Cattle — up to 10,000, by the agency’s previous rough estimate — are still being destroyed and tested at 18 properties deemed part of the “infected” herd.

Read Also

Beef industry weighs in on AAFC research cuts

The Canadian Cattle Association and Beef Cattle Research Council said cuts to federal research centres and programs will have long-term debilitating consequences for the beef industry.

Overall, about 50 properties in the two provinces remain under quarantine, affecting about 26,000 animals, while seven southeastern Alberta properties previously quarantined have been released. None of those numbers have changed since the agency’s Dec. 21 update.

A bovine TB investigation calls for the agency to trace out cattle that have had contact with cattle from the infected herd “over the course of the past five years,” CFIA said.

Thus, CFIA said on its website Friday, “it is expected that the investigation will identify additional animals that have had contact with the infected herd, and require additional quarantines, for some time.”

Tracing the movements of all animals at risk of having been exposed to, or having been the source of, bovine TB “may include herds that have provided animals to, or received animals from, the infected herd in the past five years,” the agency said.

Those traces take “significant time” to complete, the agency said Friday, and “given the scope and the complexity of this investigation, the number of quarantines required is expected to increase significantly.”

The full testing process per animal can take up to 14 weeks, the agency reiterated Friday. Animals on quarantined farms are tested using blood tests and caudal fold tests, and any potential positives from those tests are slaughtered, then checked for lesions — such as in the lungs and lymph nodes — offering visible signs of TB infection.

Since animals can be TB-positive without visible lesions, tissues from destroyed animals are also subjected to a culture test.

An animal can only be considered negative for bovine TB when a culture test — which can take eight to 12 weeks to complete — rules out a positive case, CFIA said.

The agency’s current probe follows the discovery of one Alberta cow that tested positive for bovine TB when it was slaughtered at a U.S. packing plant in late September 2016.

The TB strain in this case, the CFIA said, is not the same as any strain seen to date in Canadian livestock, wildlife or people, but is “closely related” to a strain originating from cattle in central Mexico in 1997.

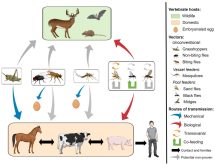

Unlike previous cases elsewhere on the Prairies, “based on this information, it is unlikely that wildlife is the source of this outbreak.”

CFIA is also carrying out “trace-in” work to learn the source of the infection in this case, but added it “can be difficult to identify, especially with cases that occur far from places where bovine TB is known to be present in wild animals.” — AGCanada.com Network